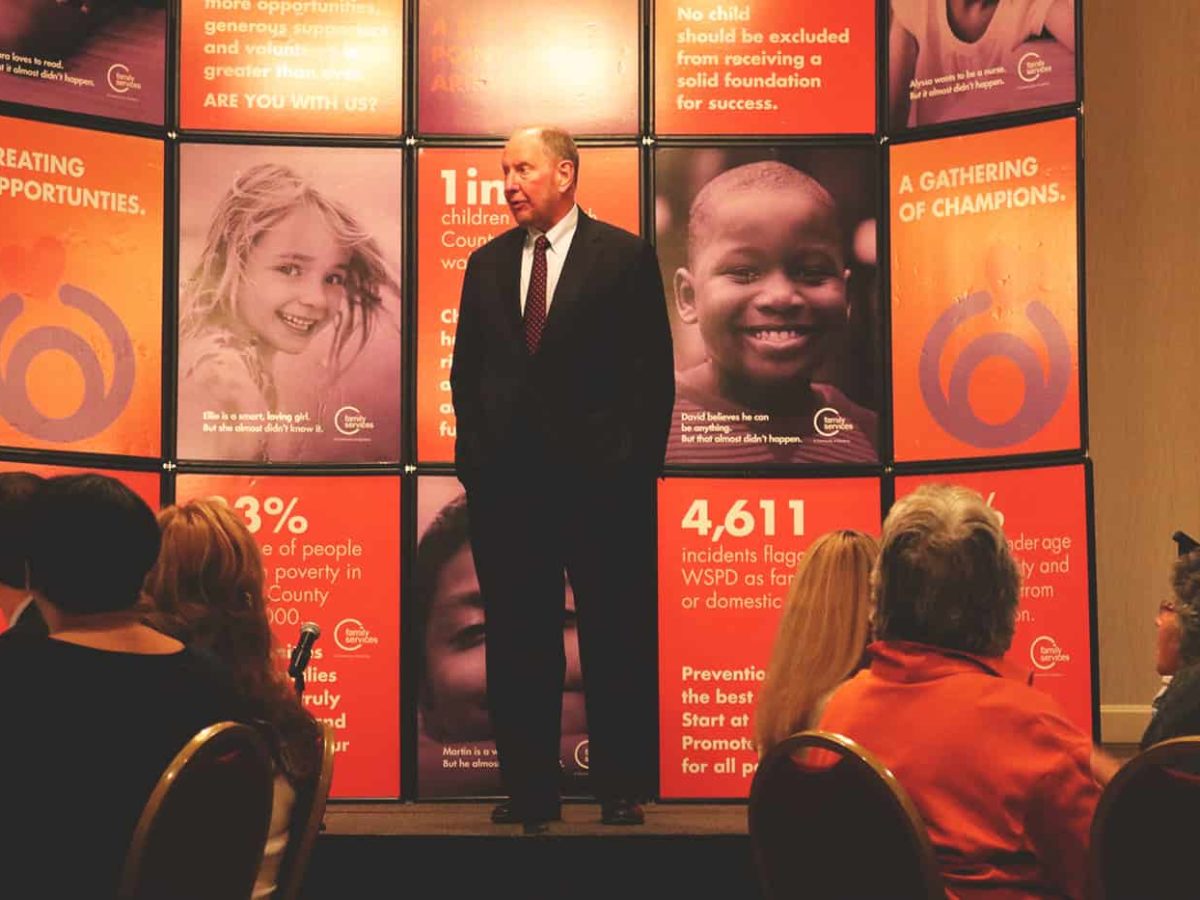

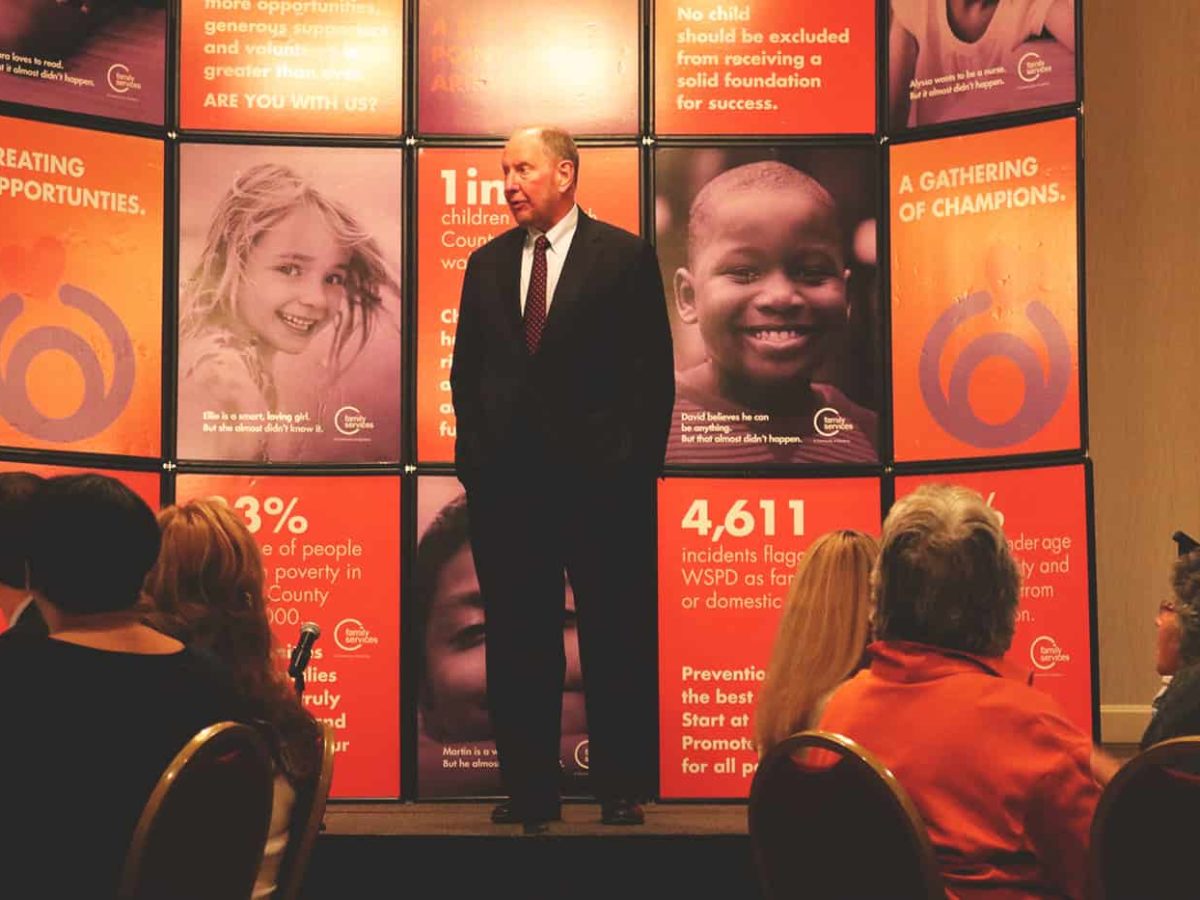

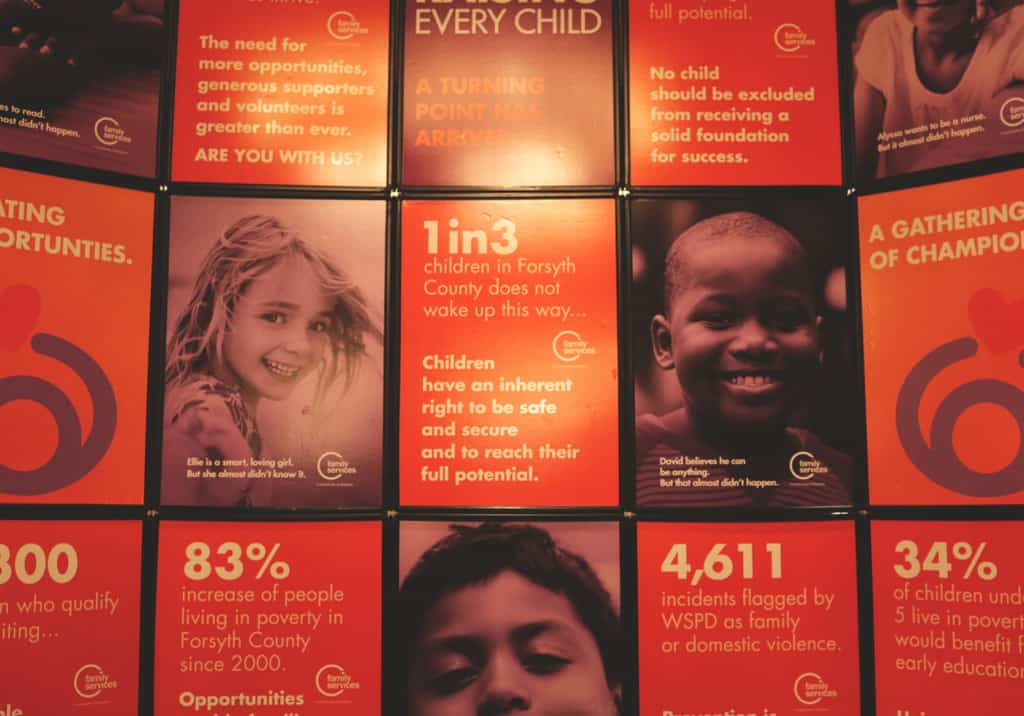

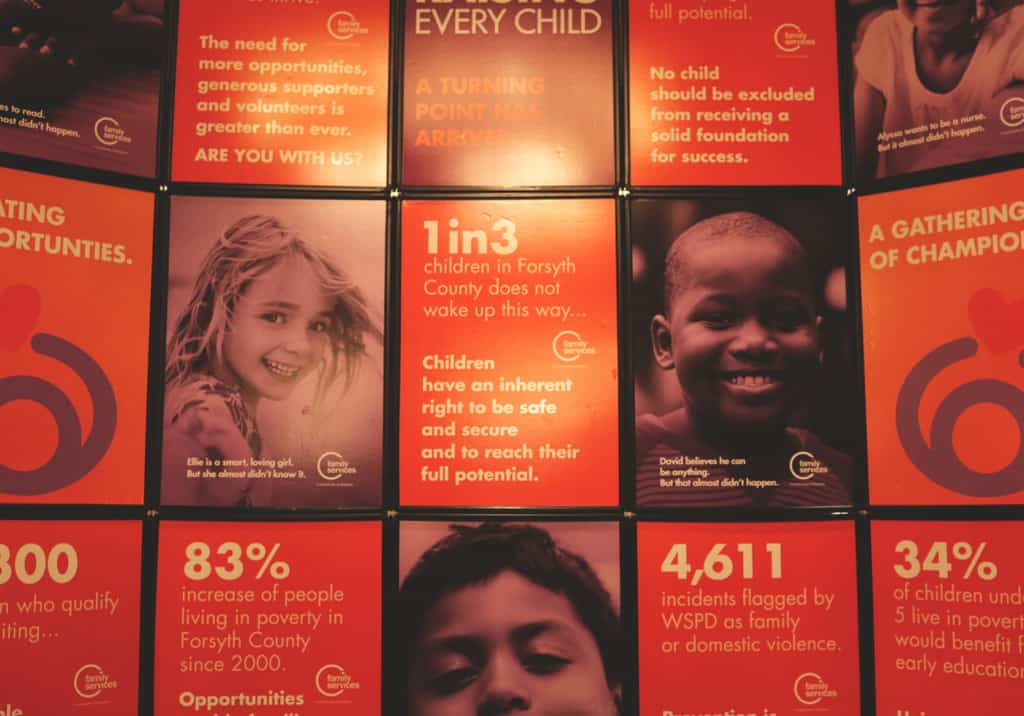

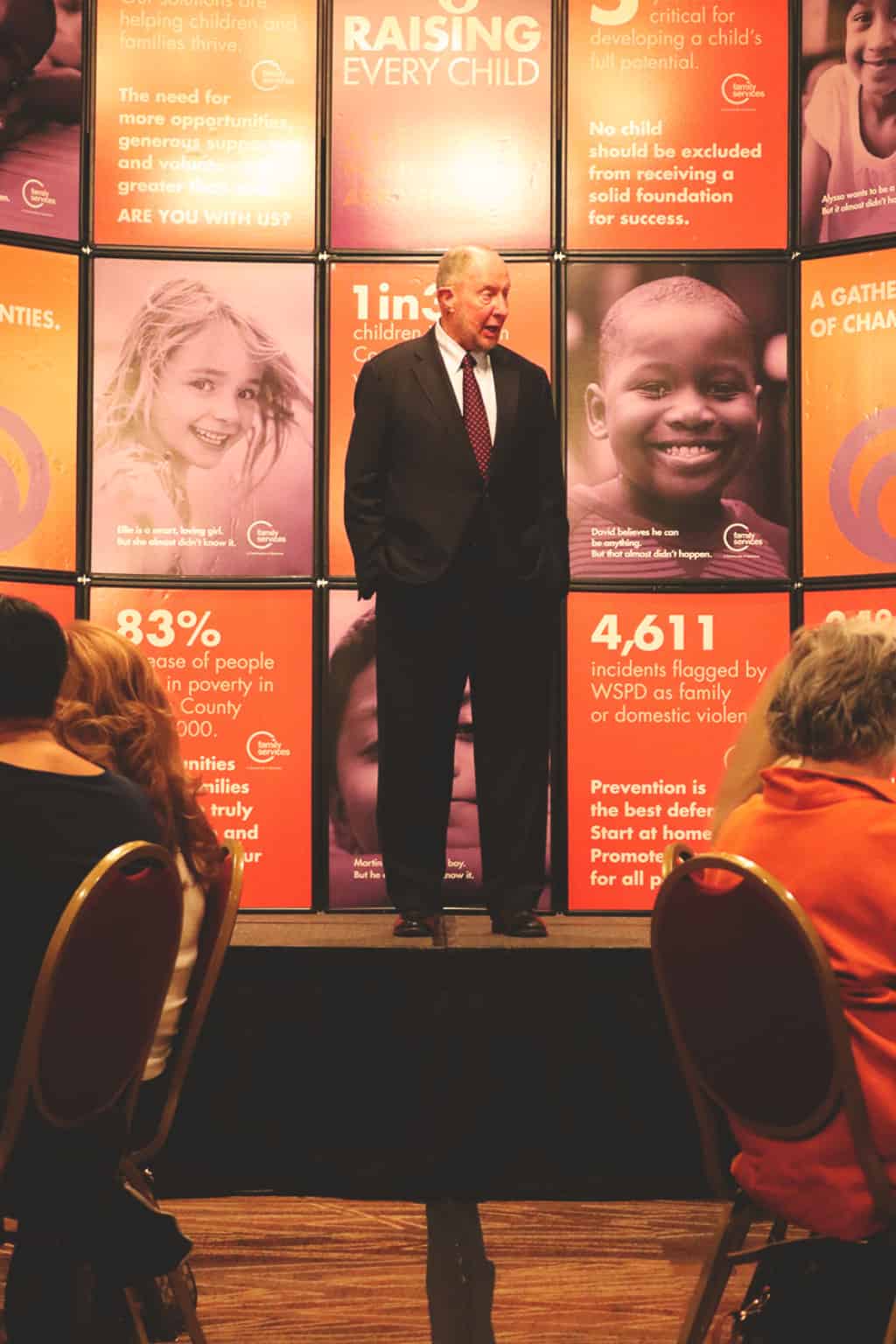

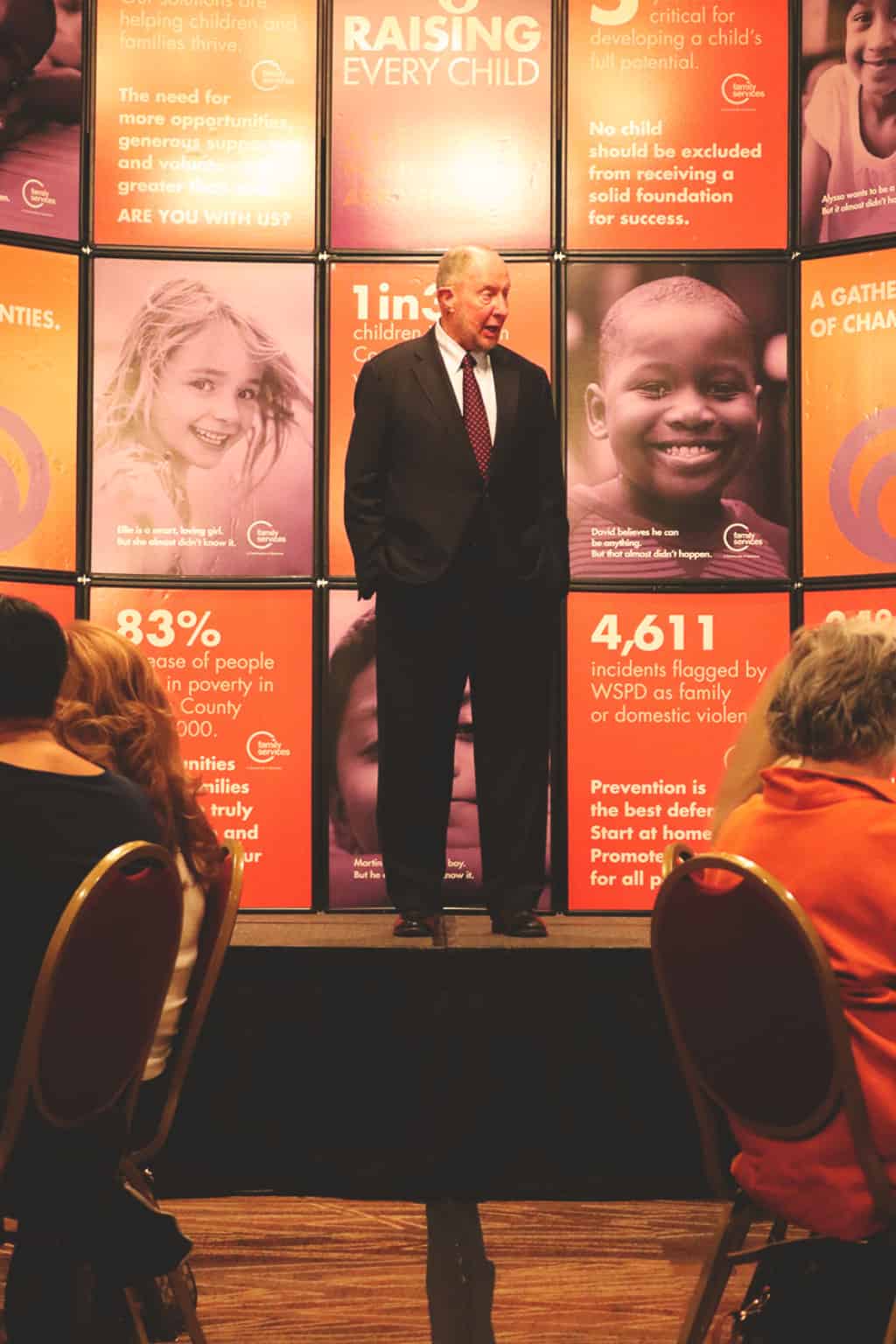

On November 1, Dr. Robert Putnam, author of Our Kids and Bowling Alone, visited North Carolina to speak at the Family Services Raising Every Child benefit luncheon in Winston-Salem.

Room is starting to fill up in Winston-Salem to hear Robert Putnam speak at @famservicesinc‘s Raising Every Child event. @EducationNC pic.twitter.com/aEN3SwBKUu

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

“At the end, I’m going to tell you why I’m optimistic about why I think we can fix this problem in our country and why I think it can be addressed here in Winston-Salem,” Putnam said at the beginning of his presentation. “I’m afraid that between now and that optimistic conclusion we’re going to go through some pretty tough evidence. I want to begin at the 30,000 foot level and ask what has been happening in America over the last 30 to 40 years. Then I’m going to slowly pan down and ask about the implications for our kids.”

Putnam noted that much social progress had been made over the past 40 years in America, citing the increased opportunities for women in the public and private sectors. Opportunities that were not available to his classmates in his hometown of Port Clinton, the setting for his most recent book, Our Kids. He also noted that in race relations significant progress had been made as well.

However, Putnam said much work still needed to be done to advance both gender and racial equality.

“Everyone in this room, for sure, knows that we have not made enough progress on issues of racial injustice and we’ve got a long way to go,” Putnam said.

And while those are still persistent and vexing issues for our nation, Putnam argued a negative cultural shift occurred while progress was being made for women and racial minorities in the past four decades.

“We have become, as a society, more divided by social class,” Putnam said. “More divided by income and by education.”

According to Putnam, the increased social sorting by income and education has set into motion a cycle of economic stagnation for the children and grandchildren of Port Clinton and children across the nation.

“We assume basically that everyone’s getting on the ladder at the same point and if some of us climb higher that’s because we’re better climbers or because we work harder at it,” Putnam said.

Robert Putnam: “Social connections across society are withered.” #raisingeverykid @famservicesinc @EducationNC

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

“Increasingly, our kids’ schools are segregated by their parents’ economic backgrounds,” Putnam said. “Increasingly, rich kids are going to school only with other rich kids, and poor kids are going to school only with other poor kids. Fewer and fewer schools in America have kids from both sides of the tracks in the same classroom. This is of course related to racial segregation, a topic of concern in this country for many years, but it is not just about race. I’m talking not just about race, I’m talking about class.”

Putnam then turned to the story of his hometown of Port Clinton, Ohio.

“I want to tell you about what’s happened to my town over the last 50-60 years,” Putnam said. “I grew up in the 1950s in Port Clinton. Port Clinton was kind of like Lake Woebegone. There was nobody very rich and nobody very poor. It was a pretty modest place.”

In the writing of his book, Putnam reconnected with some of his former classmates from the class of 1959, those who stayed and raised a family in their hometown and those who left. Those who went to college after high school and those who went to work in one of the local factories.

Their divergent stories, and that of their children, was the heart of Putnam’s message.

“Eighty percent of us have done better than our parents,” Putnam said of his Port Clinton graduating class. “Even more remarkable, the kids from the wrong side of the tracks in Port Clinton have done just as well as the kids from the right side of the tracks.”

“I’m not trying to say that Port Clinton in the 1950s or America in the 1950s was a perfect place,” Putnam said. “That’s not what I’m trying to say. My point is, that in social-class terms, this was a remarkably equal opportunity society.”

Putnam then told the story of a former classmate, who stayed in the community and began a well-paying job in the town.

“For much of his lifetime, his annual salary was larger than my annual salary,” Putnam said of his former classmate “Joe.” Joe got married and raised a family, whose children also graduated from Port Clinton High School.

“They had the same start of life their parents had,” Putnam said. “Then the bottom fell out of the Port Clinton economy. All the factories went overseas. The fishing closed up because of pollution. The mines closed. And Joe’s kids never held a steady job.”

He compared the life of Joe’s granddaughter, “Mary Sue,” in Port Clinton to his own granddaughter, Miriam. Miriam attended a prestigious college and spent time studying abroad. She had an upbringing Mary Sue could only dream of back in Port Clinton.

“They both had enormous potential, but only one of them with the accident of birth and zip code is going to live in a different universe than the other,” Putnam said.

Putnam showed the group a map of childhood poverty in Port Clinton in 1990, just after the major factories closed in the area.

Child poverty rate in Port Clinton in 1990. #raisingeverychild @famservicesinc @EducationNC pic.twitter.com/rp2XxmXkFr

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

“Then came the closing of all those factories and the downtown collapse and the boarded up shop windows you know from pictures of the Rust Belt,” Putnam said. “I want to show you how this same graph looks today.”

Child poverty rate in Port Clinton in 2008-2012. #raisingeverychild @famservicesinc @EducationNC pic.twitter.com/YoiYRwCiAl

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

Putnam noted that even though Port Clinton has been hit hard by the economic downturn, it was located on a geographical appealing peninsula on Lake Erie. The shores of Port Clinton are now home to million-dollar mansions that are reflected in the low-levels of childhood poverty in the map above.

“That area on this graph is called Catawba Island. Keep an eye on the child poverty rate on Catawba Island,” Putnam told the crowd when switching between the two maps. “The child poverty rate on that enclave has not changed at all. It’s essentially zero. There are no poor kids in that entire census tract.”

“But the rest of Port Clinton, the child poverty rate is probably 50 percent or higher,” Putnam continued. “There is a road that you can drive out of Port Clinton — East Harbor Road. If you look at the left toward the lake as you are driving along there, the child poverty rate in that census tract is zero. But if you look just to the other side of the road, at the dilapidated double-wides and the shacks, the child poverty rate is 50 percent. This is what it looks like in the tiny little town of Port Clinton.”

Putnam noted this class segregation was not unique to Port Clinton, and could be found all across the country in places like Charlotte, New York, Buffalo, rural Alabama, Atlanta, and even Winston-Salem.

“I don’t know Winston-Salem very well, but I am willing to bet you…we could get on a bus right here and in 10 minutes we’d be able to meet both Miriam and Mary Sue,” Putnam said. “That’s true across the country.”

Robert Putnam: “You can invest in your kids in one of two ways: time or money.” #raisingeverychild @famservicesinc @EducationNC pic.twitter.com/cXiOg9Utvt

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

Putnam then showed the generational effects of economic stagnation and how that can affect the lives of the children born in the two different Port Clintons.

“The amount of money that parents spend on their children per-child, per-year on summer camps, piano lessons, hockey skates, trips to Paris, computer games, and all that kind of stuff, you can see that the amount of money spent on this kind of stuff by affluent folks is rising over there,” Putnam said pointing to the graph above. “While the very same thing is not rising over here and is slightly declining…It didn’t use to be this way. Now these kids [of affluent parents] get about 10 times as much summer camp as these [poorer] kids, 10 times as much piano lessons, and so on.”

On the left-side of the graph, Putnam pointed out the amount of time spent on early-childhood educational activities, sorted by parents’ level of educational attainment.

“The amount of time that parents spend with their kids — you can divide all the time that parents spend with their kids into two forms,” Putnam said. “That is the amount of physical care parents are providing kids. In my research team, we call that diaper time. The other kind of time you spend with your kids is playing and reading and so on. We call that Goodnight Moon time.”

Putnam noted that children like his granddaughter, Miriam, are getting 45 minutes a day more of Goodnight Moon time. “Her parents read to her, her grandmother reads to her, occasionally even I read to her,” Putnam said. “All that time she was getting that, her brain was getting the right stimulation to develop positively in terms of the right social development. Mary Sue [whose stepmother kept her behind a baby gate] was not. We now know that Miriam was getting a lot of exactly the right stuff to develop her brain, and Mary Sue was not getting that stuff.”

Robert Putnam: Poor kids in America increasingly concentrated and alone. It’s a national trust gap. @EducationNC @famservicesinc pic.twitter.com/1CuUrtZr64

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

Putnam then shared a pair of charts tracking the national decline in church attendance, and levels of social trust of children of parents in the top-third in levels of educational attainment and those in the bottom third.

“These poor kids in America are increasingly isolated and alone,” Putnam said. “They can’t trust any institution. They can’t trust their parents because they’re increasingly from fragile and fractured families. They can’t trust their neighbors because they are increasingly concentrating in low-income and high-crime neighborhoods. They can’t trust their schools, because they are increasingly concentrated in low-income schools. They can’t trust their clergy because they are not at church. They can’t trust their coaches because they are not on the fields. They can’t trust anyone and they know that.”

“Think about what it means to grow up in an environment where you can’t trust anybody,” Putnam asked the crowd.

Robert Putnam: Family income matters for college completion. @famservicesinc @EducationNC #raisingeverychild pic.twitter.com/yq3FOlvt8h

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

“What matters more is not how good you are, it’s how rich you are,” Putnam told the crowd after sharing a graph that showed percent of college graduates by social-economic status. “That absolutely contradicts the idea that what we do should be a reflection of us and not our parents.”

Putnam’s graph (above) showed that only about 30 percent of students with high test scores from the low-socio economic families were college graduates. Meaning nearly 70 percent of students with high test scores did not obtain a college degree.

“That is incredibly wasteful,” Putnam said. “As a country, we cannot afford to throw away nearly three-fourths of our smartest kids just because they happen to have parents who make less income.”

And why, Putnam asked, should this bother those of us in the room, those of us from a higher socio-economic status?

According to Putnam, the cost of caring for those children as they grow into adulthood and old age will ultimately fall on people like his granddaughter Miriam.

“It’s going to cost [Miriam’s] generation five billion dollars,” Putnam said. “Young kids over there are learning very poor health habits…that means they’re going to get sicker earlier and more often. Who’s going to pay for that? My Miriam is going to pay for that. The biggest part of it, the bright kids over here [from the low socio economic group] who are not getting the right support or education…if they did get the right support or education, they would be helping the whole economy grow. This is not a matter of altruism, it’s actually costly to not help [those kids], though I do believe it is morally right to help [them.]”

What changed in the 50 years since Putnam and his class graduated from Port Clinton High School?

He shared an anecdote about his own parents and their views regarding their larger community on the shores of Lake Erie.

“If they wanted a swimming pool, it was not just in our backyard, it was at the local high school so all kids could have access to the swimming pool,” Putnam said. “The meaning of ‘our kids’ then meant all the kids in town. Over the last 30-40 years, the meaning of ‘our kids’ has shrunk. The meaning now is our biological kids. If you talk to people in Port Clinton now about Mary Sue, they say that’s a really sad story, but she’s not my kid. She’s somebody else’s problem. Let them worry about it. That didn’t use to be the case in America. That is what is fundamentally wrong. Those kids are our kids, too.”

Robert Putnam: Good news, problem is fixable because we have faced these types of opportunity gaps before, e.g., Gilded Age. @EducationNC

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

“We can fix this,” Putnam said. “We can, because we have done this before. We have changed this gap between the rich and the poor in our own history.”

Putnam noted that at the end of the Gilded Age in the 1890s, the gap between the rich and the poor in America was as high as it had ever been, and would ever be again, until present day.

The collective answer to the income gap at the time: the creation of the modern high school.

Robert Putnam: Example of a past reform in a period like ours was when America invented the High School at start of 20th Cent. @EducationNC

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

“Americans for the first time in American history, invented the high school,” Putnam said. “It did not exist prior to 1910. Small towns across the nation noticed there was a growing gap between rich and poor. They said we’re going to do something about it right here.”

“There were secondary schools, but they were all private,” Putnam said. “You had to pay. This was a big deal and a hard sell. If you were in one of those towns, you had to say to the rich bankers, farmers, and lawyers who had already paid for their kids to get four years of secondary education, you had to say to them that they ought to pay higher taxes so that other people’s kids can get those same four years. It was a hard sell but people bought it. It turned out to be the best public policy decision that Americans have ever made.”

“It’s hard for me to even convey to you what a bold, risky decision this was,” Putnam said. “They knew that high school was good for rich kids and they assumed it was good for poor kids. It was very expensive. They had to invest big sums, hoping it would return, and it turned out magnificent.”

What is 21st Century equivalent of the high school? Robert Putnam says early childhood education. @famservicesinc @EducationNC

— Todd Brantley (@jtbrantley) November 1, 2016

“Now, what’s the 21st Century equivalent of the high school?” Putnam asked the crowd. “My personal opinion is early childhood education. If [Winston-Salem] and other communities around the country say, ‘We’re going to invest big time in this effort. This will raise the productivity of this whole area and it will level the playing field.’ If you do it and talk to all the other communities around the area, if you share your experiences and share your ideas. We will look back in 20 years and people will say, ‘Thank you for leading us to solve that problem.'”

“You should do what I’m hoping you’re going to do, which is invest heavily in early childhood education,” Putnam said in conclusion. “Partly because you feel philanthropic toward poor kids here in town, and partly because you hope that you’re going to help the whole country get back on track.”