Go as far west as you can while still being in North Carolina. Then make a couple turns and look for a few trailers beside a community college. Walk into one of them and enter a classroom, unannounced.

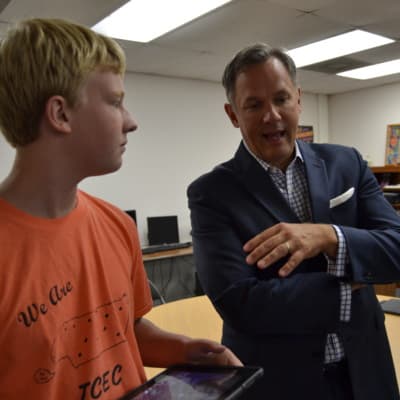

After giving Lieutenant Governor Dan Forest a tour, Tri-County Early College faculty encouraged him to do just that:

Come back, but next time, don’t tell us.

Ben Owens, a physics and math teacher at the high school in Murphy and 2014-15 National Hope Street Group Teacher Fellow, said he would be willing to base his salary off just that — an assessment of his teaching after showing up out of the blue and spending 10 minutes in his classroom.

This confidence stems from the deep-rooted belief shared by a team of 13, led by Principal Alissa Cheek and seven teachers, that they’re onto something special — a way of teaching and learning that exists nowhere else in the state.

Tri-County Early College, a public high school, receives at least 60 applicants and turns down at least 20. The application process works like a lottery after certain factors are prioritized. According to their website, 80 percent of students must be first-generation college-goers or students who are at-risk for dropping out.

During his visit, Forest discussed the school’s strategies with teachers, listened to students share their experiences, and observed students in the classroom.

The school’s curriculum is project-based. Students chose one of two projects this quarter — the math-and-science-focused “The Power of Nature,” or the humanities-based “The Power of Story.” Each has a driving question, but the teams of students are encouraged to be creative with how they answer it. The teams are picked at random and include students from different grades and skill levels. At the end of the quarter, the school has an exhibition to display the students’ final products. Then, the two groups switch and tackle the other project.

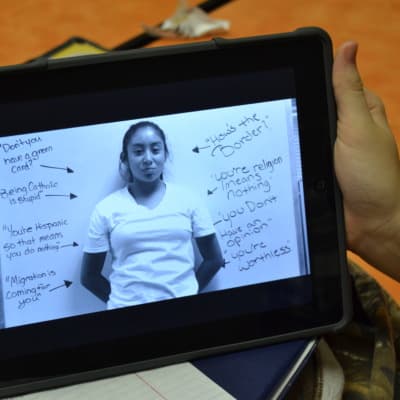

One group of students walked through their “Power of Story” project while Forest visited. They were creating videos that showed their process of overcoming adversity. The first video, they explained, would show who they are and give a glimpse into each of their struggles. They were visibly excited and played what they had so far. Each girl stood in front of white posters with what they saw as their weaknesses and “false labels” written in marker around them. They danced, introduced each other, and one girl narrated the beginning of their stories. There would be another video that shared each of their darkest moments, they explained. One would show how they each overcame those hard times to grow.

In the “Power of Nature” project, a group of students worked on a construction idea for an underwater dome. Forest, a former architect, helped them rethink the design of their model. A student explained that they wanted to power the shelter with hydroelectricity and make sure the material of the dome doesn’t interrupt the ecosystem. They shared the research they had done and thanked Forest for his suggestions.

The learning is both hands-on and connected to the real world. Later, Forest saw a student who was having a problem with a battery not charging for a project. She told the professor she had already tried calling the company, but that, “They weren’t much help.”

“That’s phenomenal,” Forest said. “I’ve never seen that in any school I’ve ever gone to, where the students are taking initiative to do these things on their own.”

As students work on their projects, they each have a checklist of the state’s competencies they must learn. When a student feels ready, he or she can go to a teacher and prove mastery over that bit of knowledge or skill. Students who have mastered a skill are often asked to teach it to a peer. Students move at their own pace, collaborate with classmates, and drive their learning. Teachers act as guides in the process. Cheek said this technique prepares students to be self-motivated for life.

“Our goal is to make them self-directed when they leave us so that, no matter what they’re doing, they’ll know where to go to figure out and who to go to without somebody telling them,” Cheek said.

Forest’s visit to Cherokee County comes in the middle of his campaign against Democratic challenger Linda Coleman. He has been an advocate for this kind of hands-on learning and mastery-based assessment during his last four years in office. Forest said getting in the classroom gives him an idea of what’s working and what’s not.

“You want to take it back and say, ‘Hey, we’ve seen these examples and where this is working really well,'” Forest said. “Let’s take that and then multiply that. Let’s duplicate it as fast as we can.”

Students also have the opportunity to take college-level courses at Tri-County Community College and can earn up to an associate’s degree before graduating high school.

Formal tests aren’t mentioned until the day beforehand. Teachers, jokingly, said they just have to remind students what a multiple-choice test is. Tri-County students, however, do well. The school has 82 percent proficiency on end-of-course tests, a 100 percent graduation rate, and an 88 percent college-staying rate.

In addition, 65 to 70 percent of students graduate with a two-year degree, according to the school’s early college liaison Jason Chambers.

But teachers say there’s something not being accounted for in the numbers, including the school performance grades measured by the State Board of Education and released last month. Tri-County Early College received a B. Eighty percent of this grade is based on academic achievement, and 20 percent is based on the school’s academic growth.

“If you simply look at our metrics, we’re like, ‘Eh, middle of the pack,'” Owens said.

Owens said those measures don’t reflect the environment that can only be experienced first-hand or the benefits early-college students are receiving.

“When they leave here, they can have an adult conversation, they can solve problems, they can collaborate with others, and those are the things that we don’t currently measure,” Owens said. “Or at least we don’t do a good job of measuring them.”

Tri-County has received a great deal of outside recognition this year. In January, Tri-County was named one of 16 Schools of Innovation and Excellence by NC New Schools, which has since closed. Just last week, Tri-County found out they weren’t chosen as an XQ Super School — a contest that awarded 10 innovative public high schools across the country with $10 million over five years. However, out of 3,000 applications, Tri-County landed in the top 50. The money would have been used to implement a renewed vision for the school and to build new and larger facilities.

“The only thing that’s prohibiting us from growing is facilities,” Chambers said. “Period. Hands down.”

He said Tri-County, which was one of the first early colleges in the nation, is now the only early college still in mobile units. “We are just like a balloon that’s about to pop,” Chambers said.

But their passion for their mission remains as strong as ever.

It’s a mission that goes beyond the staff and students of Tri-County. This year, the faculty explained to me during their planning session called Critical Friends Time, they are working on a proof of concept study. They welcome teachers to visit and learn their model as often as possible. The study will help others replicate the school’s model and, they hope, will give them the freedom from the Department of Public Instruction to transition to a complete competency-based model. Because of traditional standards like statewide testing and required seat-time, Owens said they don’t have the flexibility they need.

“If a student can master a subject in three months, then why shouldn’t that student be able to master it in three months?” said Joe Thorley, a civics, American history, and current events teacher.

Despite setbacks, Tri-County Early College faculty is dedicated to spreading its methods as far as they can.

“We want to be a true model of how high school should be done, especially in a rural context, not only in North Carolina, but across the country,” Owens said. “We honestly believe this is the way that we should be training our students for how to be good citizens and how to thrive in the real world.”