Legislators embrace vouchers, charter school expansion, disregard calls for accountability

Since taking charge in Raleigh, conservative lawmakers have been steering public dollars into a range of alternatives to traditional public schools that march under the banner of “school choice.”

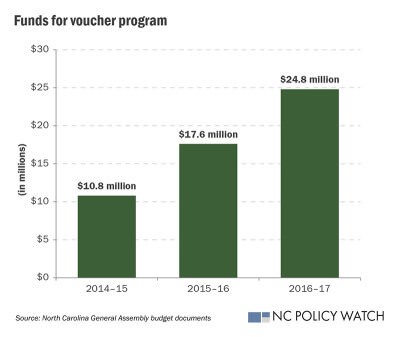

Beginning as a trickle, but with the potential to become a flood, spending is growing for vouchers to pay tuition at private and religious schools; an expanded roster of charter schools run by for-profit companies; and two virtual charter schools operated by a scandal-plagued company.

Meanwhile, those same legislators are squeezing conventional K-12 schools with budgets that place North Carolina near the bottom of national rankings for teacher pay and per-pupil spending. A central rationale for providing these alternatives is that traditional schools fall short in educating children from low-income households and communities, children of color and children with special needs.

But even as they cite end-of-grade test results and other data to demonstrate the shortcomings of conventional schools, the legislators are requiring no such accountability from voucher programs and charters. So far, there is no evidence that at-risk children fare better on average in the alternative settings and an abundance of anecdotal examples in which they are clearly worse off.

Vouchers for unaccountable private schools

In 2013, legislators opened the door for sending taxpayer funds to private schools, 70 percent of which are religious in orientation and sponsorship. And some are home schools pretending to be something more.

Public School Forum President Keith Poston discusses the decline in public school support over the last five years, as legislative support has grown for vouchers and charter schools.

School vouchers of $4,200 a year, formally known as “Opportunity Scholarships,” are touted as a way to help low-income and minority children who are falling behind in their local public schools by providing access to better options in private ones. The program is strongly embraced by conservatives, but there is concern about accountability in their own ranks.

Near the end of the 2015 legislative session, a group of Republicans in the House banded together to block a proposal by school voucher champion state Rep. Paul “Skip” Stam (R-Wake) that would have put the voucher program on track for a major expansion. Among them was state Rep. Leo Daughtry (R-Johnston), who described one school in his district benefiting from the vouchers.

“I went to visit this school,” Daughtry said. “It’s in the back of a church, and it has like 10 or 12 students – and one teacher, or one-and-a-half teachers. I think you need to go slow with Opportunity Scholarships. From what I saw, [it] didn’t seem to be a school that we would want to send taxpayer dollars to.”

Before the voucher program began, there was little concern about the low level of state oversight of private schools because they received no public money. The voucher money is flowing now — $11 million this year, with $24 million budgeted for 2016 — but private schools are subject to minimal requirements for student assessment and none at all for curricula, instructional staff or financial viability. The schools can choose the pupils they want to admit and are free to provide religious instruction.

Only low-income families are now eligible for vouchers, but it is expected that those requirements will ease in the future.

Public school advocates and other stakeholders mounted a legal challenge to the program soon after its inception. They won the first round when Franklin County Superior Court Judge Robert H. Hobgoodruled that the program violated the state constitution.

“The General Assembly fails the children of North Carolina when they are sent with public taxpayer money to private schools that have no legal obligation to teach them anything,” he wrote.

Early this year, the state Supreme Court overturned Hobgood’s order, allowing the voucher program to continue without requiring any additional accountability.

Charter schools expand their market share

In 2011, North Carolina lifted the cap on the number of charter schools that can operate in the state. When first established in the 1990s, the schools were billed as laboratories of innovation, where best practices could be developed and shared with local public school systems. With the expansion, legislators diverted more funds from traditional schools and increasingly into the hands of for-profit operators.

Some charters provide students with an exceptional education. Typically those high performers are well-resourced, with strong community support and often with additional funding from philanthropic interests.

Charter schools that don’t attract extra funding and community support are at risk of poor academic and financial performance. The schools receive per-pupil funding that matches traditional public schools, but they’re not subject to the same oversight and accountability standards. State oversight has become even spottier in recent years because staffing has not grown to keep up with the increased number of schools.

Problems have ensued. A 2015 state auditor’s report found that a Kinston charter school’s CEO mismanaged hundreds of thousands of dollars over several years. The school shut down just a few days into the 2013-14 school year, leaving its students academically homeless.

Three Charlotte-area schools also abruptly closed in the last year because of financial woes and poor governance. In all instances, reviewers of these schools’ applications for charters expressed reservations about the schools’ ability to survive and succeed.

And questions continue to dog Eastern North Carolina charter operator Baker Mitchell, Jr., who runs four charter schools and has received millions in taxpayer money through his for-profit companies, which lease the land to the schools and run their operations. His notoriety spurred a critical investigative report by the national media outlet ProPublica last year.

Virtual charters lobby their way into N.C.

The 2014 state budget contained a provision calling for two online charter school companies to establish a four-year pilot program in the state. Supporters of these virtual charter schools say they’re a necessary option for children who don’t do well in traditional schools because they need remedial help or advanced learning; have health issues; full extracurricular or athletic schedules; or are dealing with bullying.

The report, issued in October by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University, concluded, in part: “The majority of online charter students had far weaker academic growth in both math and reading compared to their traditional public school peers. To conceptualize this shortfall, it would equate to a student losing 72 days of learning in reading and 180 days of learning in math, based on a 180-day school year.”

One of the companies enlisted to open a virtual charter in North Carolina is K12, Inc., which had lobbied for years for the program. A publicly traded company whose CEO earned $4 million in total compensation for 2014, K12, Inc., backs virtual charter schools across the country, including California-based CAVA (California Virtual Academy).

Jan Cox Golovich quit her job as an online high school teacher at CAVA two years ago, having concluded that her students were being cheated out of an education. “CAVA lets students fail,” she said in an interview with N.C. Policy Watch. “They let the kids go a whole year performing poorly in school and then fail. But CAVA has made their money.”

CAVA was also the subject of a critical report by In the Public Interest, a Washington-based think tank. The report found poor oversight when it came to ensuring accurate student attendance, dramatically lower test scores than their traditional public school counterparts and difficulty accessing technology.

Combined, the two virtual schools in North Carolina could receive up to $66 million a year in taxpayer funds by 2017 if enrollment reaches a combined 6,000 students by then, according to the Associated Press.

This article was first published by NC Policy Watch on December 10, 2015.