Release of the first letter grades for North Carolina public schools on February 5 led to predictable debate over their fairness and usefulness. Whatever their limitations, though, the letter grades sent a clear message about what North Carolina needs to do to improve outcomes for kids.

In a nutshell, we need to figure out how to break the link between poverty and achievement in our schools.

In a nutshell, we need to figure out how to break the link between poverty and achievement in our schools. A crucial first step is to support policies and programs that directly address the particular challenges that poor students bring with them to school.

The most striking pattern that emerged from the letter grades from the NC Department of Public Instruction was the near-perfect correlation between letter grades and economic disadvantage. The News & Observer reported that 80 percent of schools where at least four-fifths of children qualify for the federal free or reduced lunch received a D or F grade, whereas 90 percent of schools with fewer than one in five students on the subsidized lunch program received As or Bs.

This pattern comes as no surprise.

The fact that, on average, students from disadvantaged households perform less well in school than peers from more advantaged backgrounds has been documented at all levels of education.

Sean Reardon of Stanford University has shown that the achievement gap between children from very high- and low-income backgrounds has grown dramatically during the past 50 years and now far exceeds the gap between white and black students. Likewise, results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress show that average achievement levels are far lower in states such as Mississippi and Arkansas, where child poverty rates exceed 25 percent, than in many New England states, where child poverty rates are less than half that level. Even within countries such as Finland and Korea whose students score near the top of international tests, those from disadvantaged homes do far less well, on average, than their more privileged peers.

… for the first time in recent history, a majority (51 percent) of students in the nation’s public schools come from low-income families.

The urgency of addressing the impact of poverty on achievement was highlighted earlier this month when the Southern Education Foundation released data showing that, for the first time in recent history, a majority (51 percent) of students in the nation’s public schools come from low-income families. In North Carolina the proportion is even higher – 53 percent.

When it comes to making effective education policy, the issue is not whether family background is correlated with educational achievement. The question is how we choose to deal with this empirical reality.

The ideal policy response, of course, would be attack poverty itself. Achievement gaps did narrow in the years following Lyndon Johnson’s “war on poverty” in the 1960s. But doing so would take a long time.

A second possible response would be to put one’s head in the sand and simply ignore the relationship. Unfortunately, that is exactly what the dominant federal policy initiative of the Bush and Obama administrations’ No Child Left Behind policy has done. NCLB sets the same high – and ultimately unreachable – achievement expectations for all students, and it then holds schools accountable for assuring that all students meet them. The inherent futility of this approach – echoed in the criteria that guide North Carolina’s system of letter grades for schools – helps explain why the administration has had to grant waivers to many states.

Policymakers often rationalize their denial of the relationship between poverty on achievement because they sincerely believe that schools should offset the effects of low socio-economic status. Others fear that setting lower expectations for some groups of students – what President George W. Bush called the “soft bigotry of low expectations” – will become a self-fulfilling prophecy. But in both cases, simply wanting something to be true does not make it true.

Absolutely no evidence exists that the few success stories can be scaled up to address the needs of large proportions of disadvantaged students.

Still other policymakers cite examples of schools serving low-income students, such as some of the Knowledge as Power Program (KIPP) charter schools that have managed to “beat the odds” with disadvantaged students. Consistent with such exceptions, according to The News & Observer, about 5 percent of North Carolina schools where at least three-fifths of students qualify for subsidized lunches, received As or Bs as letter grades, some of them charters. But such successes are often largely attributable to these schools’ success in attracting students from the high end of the ability or motivational spectrum, or to substantial supplemental funding from foundations, or to extremely hard work of their teachers. Absolutely no evidence exists that the few success stories can be scaled up to address the needs of large proportions of disadvantaged students.

The consequences of the failure of recent federal and state education policies to confront the important role of family background in student achievement have been profound. While failing to narrow the achievement gap, the policies have inflicted widespread collateral damage in the form of narrowing the curriculum, low teacher morale, and in some cases outside of North Carolina, cheating by teachers and principals facing pressure to achieve impossible goals.

So if poverty reduction is off the policy table, and denial of the important role of family background is unproductive, how should policymakers deal with the impact of poverty on educational performance?

A third … approach is to acknowledge that while we are not going to be able to eliminate poverty any time soon, we can find ways of targeting the specific ways in which poverty hampers learning.

A third – and far more preferable – approach is to acknowledge that while we are not going to be able to eliminate poverty any time soon, we can find ways of targeting the specific ways in which poverty hampers learning. Put another way, we can address the particular challenges that disadvantaged children face as they pursue their education.

Fortunately, we already know a lot about these challenges. A wide body of research has demonstrated how poor health care – both physical and mental – and the lack of quality early childhood education translates into low cognitive performance. Research by one of the authors, Helen Ladd, and two colleagues has shown that quality early education programs reduce the need for spending on special education later on.

Other research has documented how poor children often have limited access to the language and problem solving skills that serve as springboards to future learning. We know how family poverty also translates into limited access to books and computers at home or to the enrichment that comes from vacation travel.

Incidentally, to say that schools need to address the context in which their students live is not, as many critics charge, to “let schools off the hook.” We need to set high performance standards and expectations for schools, including those serving large proportions of disadvantaged pupils, staff them with competent teachers, and pursue school improvement efforts with vigor. The point is that schools cannot address these challenges all by themselves.

The challenge for policymakers is to look for ways to minimize the impact of the particular challenges that many disadvantaged children face. We should, in short, look for ways to provide children from low-income families with the same sort of education-enriching experiences and resources that middle-income children take for granted.

At least three types of interventions offer promise:

School-based health clinics and social services. Most other developed countries are far ahead of the U.S. in addressing the health and developmental needs of their children and thereby assuring that students are physically and mentally ready and able to learn. Ways to do this include locating health clinics in schools and forming school-based teams of nurses, counselors, and teachers that meet on a regular basis to address the challenges of individual children.

Early childhood and pre-school programs. A huge body of research in the U.S. and elsewhere has demonstrated that high quality early childhood education pays off not only in terms of future school achievement but non-academic factors such as higher graduation and employment rates, higher income levels and less involvement with the criminal justice system. A realistic goal is to assure that every child who enrolls in kindergarten has had a quality pre-school experience.

After school and summer programs. Research has shown that children in low-income families experience far more learning loss during vacations, especially over the summer, than do their peers from more affluent families. Providing quality enrichment activities during non-school time can go a long way toward improving academic performance. The key word is quality.

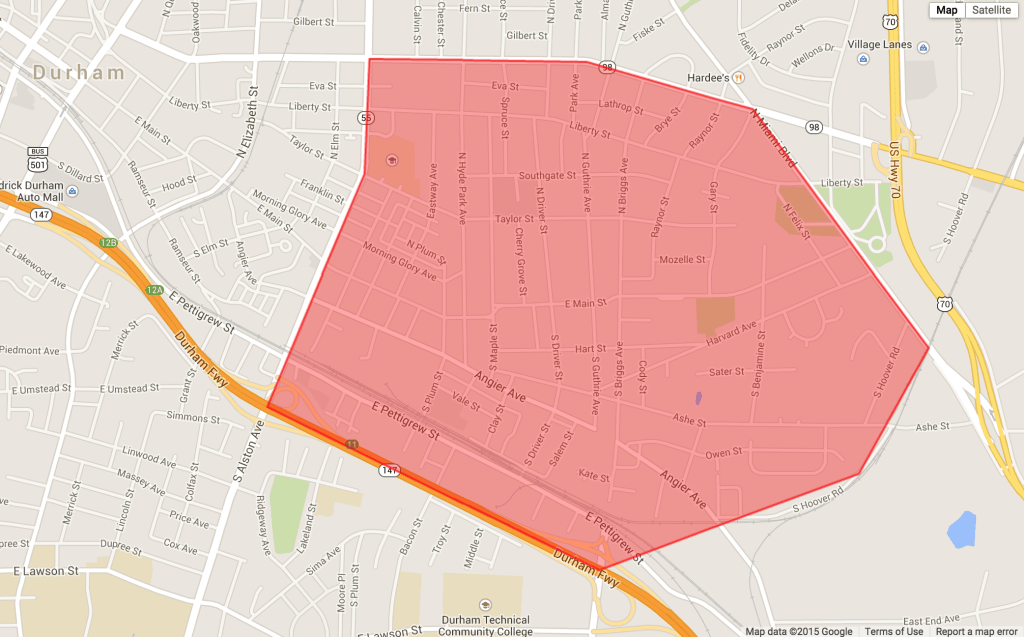

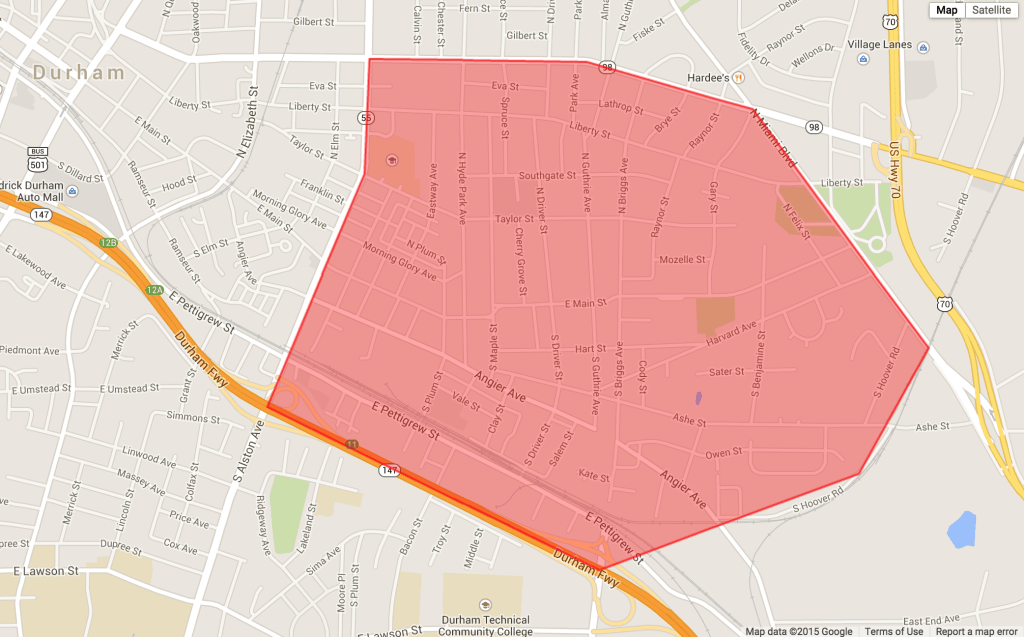

A good example of how to address the special challenges that low-income students face is the East Durham Children’s Initiative (EDCI) in Durham, NC. Loosely modeled on Geoffrey Canada’s well-known Harlem Children’s Zone in Manhattan, EDCI provides “wrap-around” education, health, counseling, and social services to children and families in a 120-block section of one of the city’s poorest sections.

EDCI does not seek to create its own programs or accumulate real estate. Rather it works to coordinate – and magnify – the work of 20 “community partner” organizations already operating in the zone. These range from Durham Public Schools and the Durham County Health Department to Duke University, the Kidznotes music program, and the Inter-Faith Food Shuttle. Only when a need seems to be going unmet does EDCI step in to establish its own program, such as its summer lunch program. It also pays for four “parent advocates” who function as liaisons between an elementary school and its families as well as two early childhood parent advocates.

The beauty of the EDCI approach to reducing the impact on poverty on achievement is that it has the potential to be replicated in any urban area.

The beauty of the EDCI approach to reducing the impact on poverty on achievement is that it has the potential to be replicated in any urban area. Leaders can come together to define a geographic target area, do a canvas of the educational and social agencies already working in that area, and develop a mechanism by which they can work together, in effect, to create a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts. The major preconditions for such an effort are strong community leadership, a vigorous nonprofit sector, and a local culture that promotes cooperation rather than competition among various public, nonprofit, and private organizations and agencies.

The release of letter grades by the Department of Public Instruction has made it impossible for policymakers to continue to ignore the impact of poverty on student learning. It’s time for North Carolinians to make serious efforts to support the many programs that, like EDCI, address the special challenges that students from low-income backgrounds bring with them to school.