Share this story

- Rising challenges are discouraging some leaders from going into the field, the @chiefsforchange report says, or compelling leaders to leave earlier than planned. In NC, 30 of the state’s 115 school districts have superintendent turnover this school year.

- "Whatever school boards can put in place to help the work of the superintendent be less challenging and less fraught, less subject to burn out, accrues to the benefit of the students they serve," said one expert on school governance.

|

|

The K-12 superintendency is more complex and demanding than ever before, according to a report published last week by Chiefs for Change, a bipartisan group of education leaders.

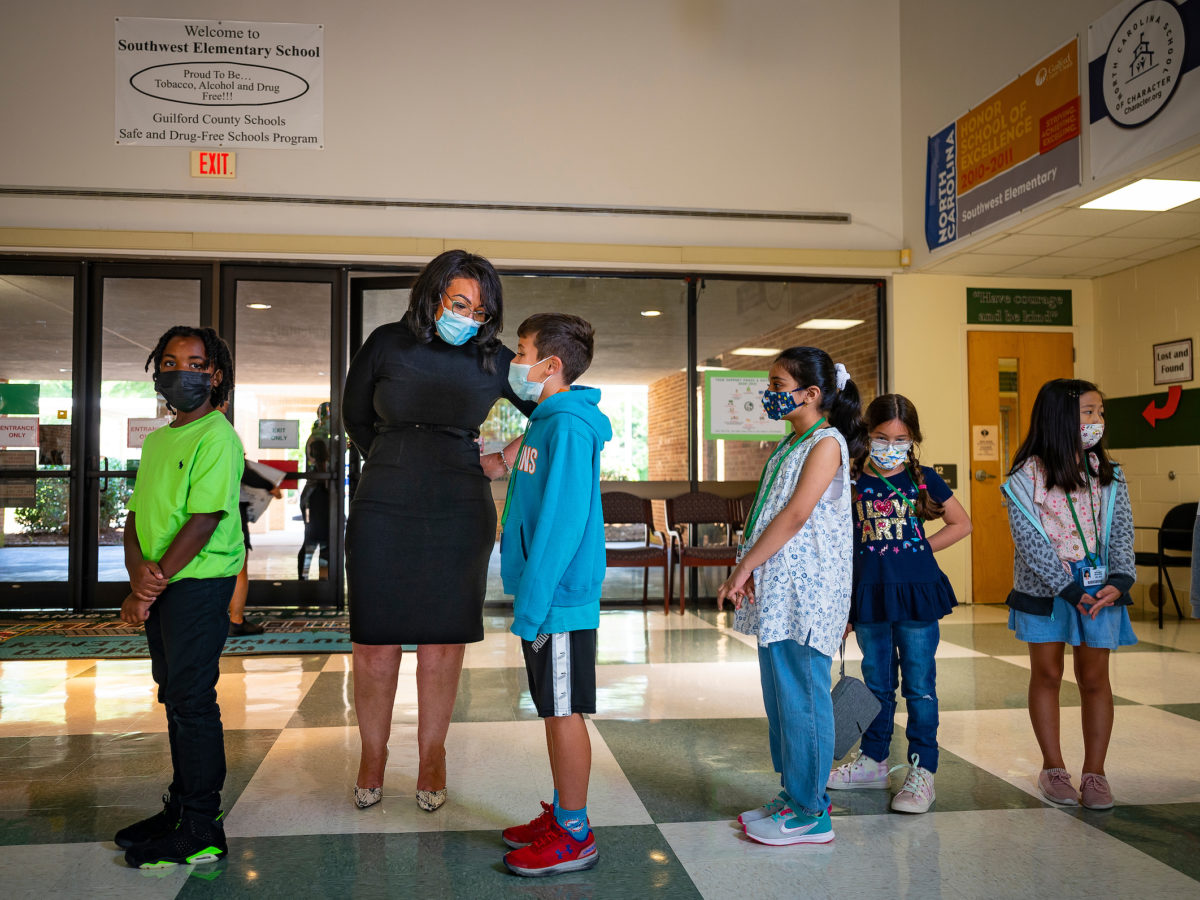

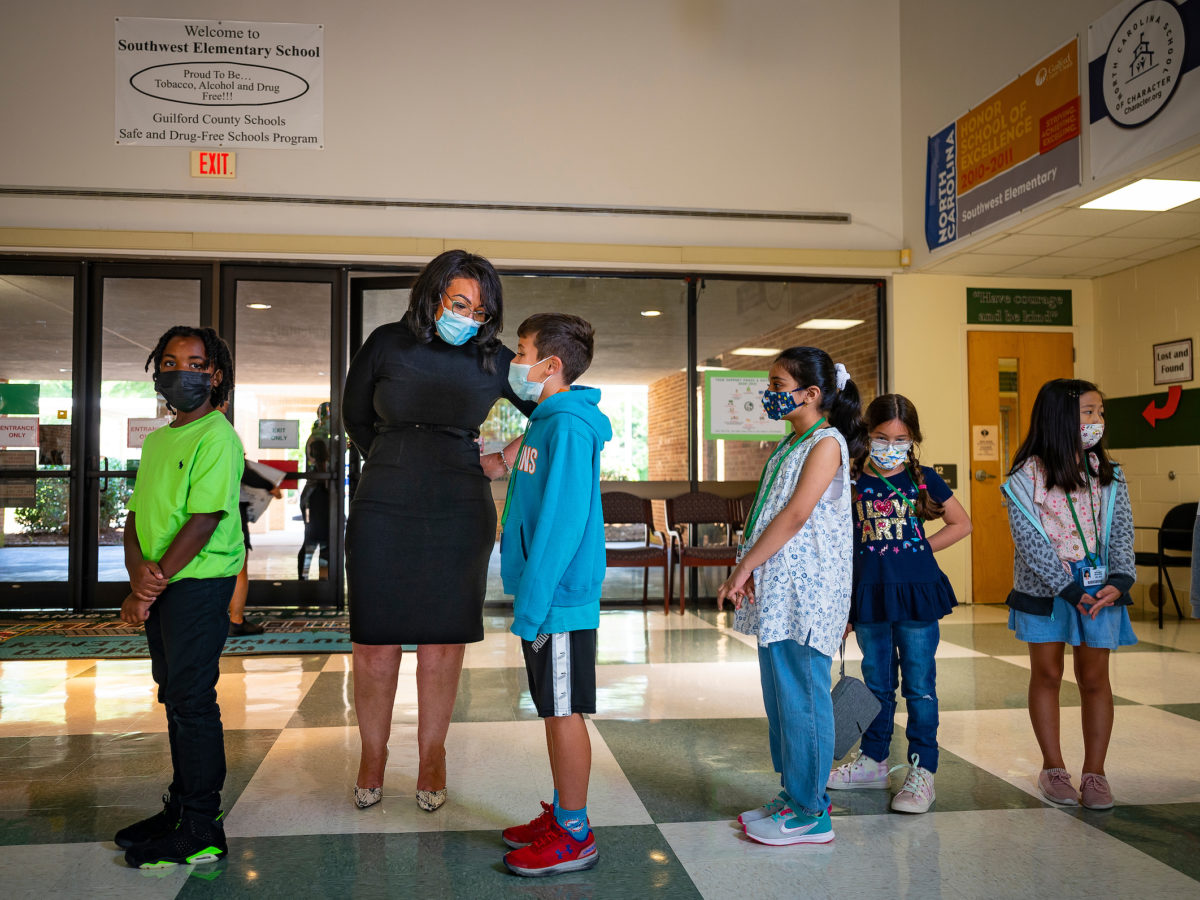

The report, “The State of the Superintendency: Insights on how to navigate K-12 leadership in a challenging and politicized education space,” provides takeaways from six former superintendents – including Dr. Sharon Contreras, the superintendent of Guilford County Schools from 2016-2022. She made history as the first woman, first Latina, and second Black superintendent of Guilford County Schools.

Rising challenges are discouraging some leaders from going into the field, the report says, or compelling leaders to leave earlier than planned. Such challenges include increasingly polarized and politicized environments, the growing dependence on the social safety net schools provide, and changing technology, among others.

“The current environment is very tumultuous for educators, particularly superintendents,” Contreras said. “It is tumultuous and stressful. I think the stress sometimes impedes innovation, and steals the joy that many once had in the profession.”

In North Carolina, as EdNC previously reported, 30 out of the state’s 115 school districts have new or are hiring new superintendents ahead of the 2023-24 school year. That means 26% of N.C. districts are facing turnover this school year – losing 193 years of experience in the superintendency, according to Jack Hoke, executive director of the North Carolina School Superintendents’ Association.

The hiring process reflects persistent gender and racial disparities in K-12 leadership. Of the N.C. districts where a superintendent has been named, eight of 17 are women. Just four of 17 are people of color. And this year, none of the 115 school districts have a Latinx leader.

According to a 2022 RAND report on superintendent turnover and satisfaction, 95% of superintendents agreed or strongly agreed that the job of the superintendent has gotten harder. Still, 85% agreed or strongly agreed that “considering everything, I am satisfied with my job as a superintendent.”

For many superintendents, perpetual and increasing stress contributes to turnover, according to the Chiefs of Change report. Superintendents are stressed about relationships with their school boards – heightened by the political environment – and frustrated by the increasing amount of time spent discussing so-called “culture wars,” rather than discussing how to better serve their students.

As EdNC previously reported, they are also worried about the expansion of school choice, the role of public education in democracy, the influence of social media on the public’s perception of public schools, inadequate school funding, and the educator pipeline.

“As the role of a superintendent has evolved, so too have the skills needed to effectively lead a school system,” the report says. “A superintendent must have a deep understanding of the education landscape; they also need business acumen, political savviness, and communications skills. Furthermore, they are stewards of taxpayer dollars, operating budgets that can be billions of dollars a year.”

Along with Contreras, the report features insight from five other former leaders, listed below. Chiefs for Change also spoke with A.J. Crabill, an author and school governance expert who currently serves as the Conservator of DeSoto Independent School District in Texas.

- Dr. Katy Anthes, former commissioner of the Colorado Department of Education.

- Dr. Chad Gestson, former superintendent of the Phoenix Union High School District (Arizona).

- Dr. Monica Goldson, former CEO of Prince George’s County Public Schools (Maryland).

- Dr. Michael Hinojosa, former superintendent of the Dallas Independent School District (Texas).

- Dr. Barbara Jenkins, former superintendent of Orange County Public Schools (Florida).

You can read the full report at this link.

The future of the superintendency

In 54 of North Carolina’s 100 counties, the school district is the largest employer. The superintendent is the CEO, the report says.

That reality means superintendents are involved in a lot more than the public usually expects, Goldson said.

“As superintendent, I led the county’s largest employer. I would love to say the job was only focused on academics and achievement, but that’s not the case,” she said. “My time was also spent on negotiations with labor unions, creating the first public-private partnership to address our aging infrastructure, and working on community challenges like food insecurity and violence.”

In order to better meet student needs today, the former superintendents said that “leaders who share the mission with stakeholders will increase the odds of success.” Though challenging, leaders said that fostering community engagement with parents, elected officials, the school board, and other stakeholders is necessary to serve all students well.

“Anything we can do to remove any and every barrier for kids to be connected and engaged,” Gestson said.

The superintendent can also be thought of as a “communicator in chief,” the report says. As such, superintendents should communicate early and often – acting as the biggest cheerleader for their district.

Superintendents must have “thick skin,” the report says, in order to not take it personally when people disagree with them. At the same time, according to Contreras, school districts should work to present a unified approach.

“Too often superintendents are out in front alone. The public then thinks that superintendents are responsible for everything,” Contreras said. “I think we have to share this space with our school boards, with other elected officials, faith, civic and business leaders – because so much of what happens in a school system is directly related to what is happening in the larger community.”

The former leaders gave several other pieces of advice on navigating the superintendency well:

- To thrive, earn support from the board, staff, and community.

- Take care of yourself or you can’t effectively care for others.

- Build a capable team and strengthen your skills as an executive.

- Lead with focus, desire, and courage.

- Listen to others.

- Establish a network of professional support.

“We can’t underestimate the value of coming together in support of one another,” Goldson said.

Self-proclaimed “student outcomes evangelist” A.J. Crabill also offered advice on how to build stronger, more positive relationships with school boards.

In North Carolina, this is particularly important as more school boards become partisan. EdNC previously reported that of the 83 school districts that had elections last November, 41 were partisan races – up from 10 districts in 2013. There are several bills seeking to further increase that number this long session.

First, Crabill said, superintendents should remember that the collective board is their supervisor, not each individual member. Some disagreement between board members and the superintendent is healthy, Crabill said.

Superintendents should also encourage their board to adopt an approach to governing that is more focused on student outcomes, he said. Crabill believes at least 50% of superintendent evaluations should focus on student outcome goals.

“It is a critical step in insulating superintendents from having to chase local politics and in helping them stay focused on the main reason for which school systems exist: to improve student outcomes,” he said. “Superintendents must be obsessed with improving the quality of instruction that students are experiencing every day.”

But doing so makes for an “incredibly challenging job,” Crabill said.

“They are constantly being asked to pour out their cup into others, and there is really no one in the organization who is typically making it their business to pour into the superintendent’s cup,” he said. “…So whatever school boards can put in place to help the work of the superintendent be less challenging and less fraught, less subject to burn out, accrues to the benefit of the students they serve.”