Editor’s Note: This article has been updated with information and data from the N.C. Department of Public Instruction.

The number of low-performing schools in North Carolina is on the rise, but not necessarily for the reasons you might think.

For 2014-15, 581 public schools — traditional and charter — met the qualification for low performing, but only because the qualification was changed by the General Assembly in the recently passed budget.

The new definition says that a school is low performing if it receives a D or F and doesn’t exceed academic growth.

Prior to the General Assembly’s new definition, low-performing schools were those that did not meet growth and had less than 50 percent of students scoring at or above Achievement Level III (there are five achievement levels total) on End-of-Grade and End-of-Course tests, according to Tammy Howard, director of accountability services at the state Department of Public Instruction. Basically, that’s grade level.

In 2013-14, when the prior definition applied, only 367 schools were low performing. That means the number increased from 2013-14 to 2014-15 by 214 schools for a 58.3 percent increase.

As already reported, the two districts with the most low-performing schools in 2014-15 were Charlotte-Mecklenburg with 37 traditional and nine charter schools, and Guilford with 42 traditional and two charters.

In 2013-14, Charlotte-Mecklenburg had 16 low-performing traditional public schools and Guilford had 12. Remember, that’s under the old definition.

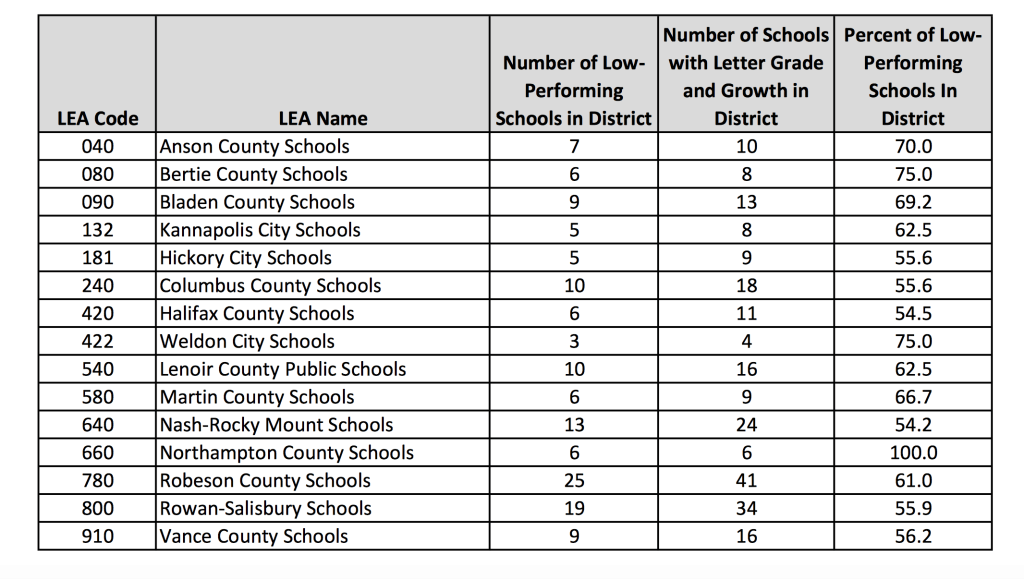

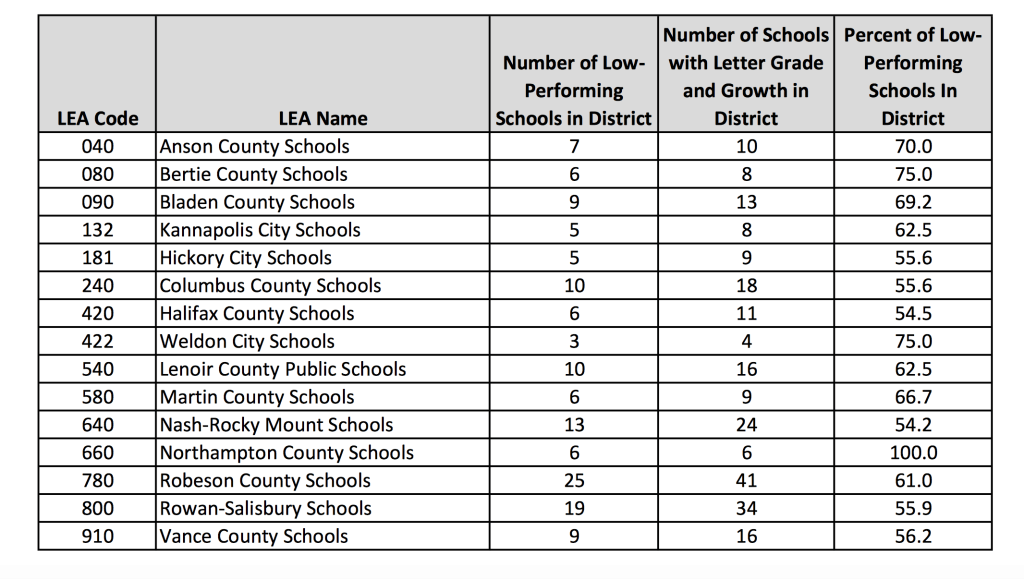

Even with the new definition and increased number, neither of those two districts gets the dreaded classification of low-performing district, reserved for areas where more than half the schools are low performing.

Fifteen districts in North Carolina received that for 2014-15, including Northampton where all six schools measured are low performing, giving it the highest percentage in the state. But using the old definition, Northampton would have had three schools qualify as low performing in 2014-15. In 2013-14, under the prior definition, it also had three.

Another low-performing district, Halifax, has been much reported on at EducationNC. Under the previous definition, it would have only had two schools that qualified as low performing in 2014-15, the same number it had in 2013-14 also under the old definition. Under the new definition, six out of the 11 schools that are measured are low performing for 2014-15. The change in definition not only increased the number of schools that are considered low performing, but also qualified the entire district as such.

If you apply the old definition to the 2014-15 data, only two of the districts — Rowan-Salisbury and Martin — currently considered low performing would be on the list. Here’s that 2014-15 list again with the number of low-performing schools under the prior definition. Recall, more than half the schools in a district must be low performing for the district to be considered a “low-performing district.”

Anson: 4 out of 10

Bertie: 1 out of 8

Bladen: 6 out of 13

Kannapolis: 3 out of 8

Hickory: 3 out of 9

Columbus: 4 out of 18

Halifax: 2 out of 11

Weldon: 0 out of 4

Lenoir: 8 out of 16

Martin: 5 out of 9

Nash-Rocky Mount: 9 out of 24

Northampton: 3 out of 6

Robeson: 14 out of 41

Rowan-Salisbury: 18 out of 34

Vance: 6 out of 16

If all of this seems arbitrary, that’s because it is, according to Terry Stoops of the libertarian John Locke Foundation.

“There is no universal definition of a ‘low-performing school,'” he said. “Criteria used to classify schools have always been, and always will be, arbitrary.”

The ramifications of the new low-performance definition have yet to be seen. The consequences right now include: parents must be informed about the status of their childrens’ schools; the schools or districts must come up with improvement plans; and district superintendents have to take some sort of action against a principal if he or she had been at the school more than two years — the possible options include remediation or dismissal.

State Intervention

DPI has a District and School Transformation division that works to improve educational outcomes in low-performing schools. Efforts by DPI predate the current definitions of low performing and will continue in the future when and if the definitions change.

In Halifax, for instance. Until recently, Halifax was dead last in the state for achievement — 115 — and only just moved up to 113 on that list. And Leandro Judge Howard Manning once said that an “academic genocide” was taking place there.

Halifax also had a large per pupil expenditure of $11,021 per student last year, which exceeds North Carolina’s average of $8,477, as explained by Stoops in this John Locke Foundation article. The large per pupil expenditure is thanks mostly to federal funds granted districts with large amounts of economically disadvantaged students.

Despite the fact that last year Halifax only had two schools qualify as low performing, the state has been intervening with vigorous turnaround efforts in the district since 2009 by consent order under Leandro.

Vanessa Jeter, director of Communication and Information Services at DPI, said that the definition of low performing has a “relationship” with the schools DPI targets for transformation, but the calculus the turnaround department uses is far more complicated.

“…[T]hrough all of the years that we’ve identified low-performing schools, we’ve never really had the resources to necessarily intervene in each and every one identified as low performing. So we’ve had to make selections based on their need, based on their district’s capacity to intervene with that school and issues of that sort,” she said.

Halifax Improvement Plan

“The underlying question is whether parents, teachers, and administrators will use the ‘low performing’ classification as additional motivation to improve student achievement. I suspect that some will,” Stoops said. “Regrettably, others will choose to maintain the status quo.”

At the November 2 meeting of the Halifax Board of Education, the board heard a presentation on the district improvement plan developed by district officials.

The plan aims to transform the way Halifax Schools approach education in an attempt to bring students out of the educational gully some have fallen into. It includes strategies on professional development, purchasing of resources, instruction, better use of data, and more. Review the plan here.

And it has lofty goals for 2015-16:

“Each school will show a minimum increase of 30 percent in its performance composite.”

“Each elementary, middle, and high school will ‘exceed expected growth’ as determined by the State’s Accountability data to prevent from being low performing.”

Halifax assistant superintendent Tyrana Battle said the improvement plan goes “hand-in-hand” with the district’s strategic plan, which outlines even loftier goals.

“By the end of the 2015-2016 school year, schools with a letter grade less than ‘C’ will increase their performance composite to 60% or better AND exceed expected growth; schools with a letter grade of ‘C’ or better will increase their performance composite to 70% or better AND at least meet expected growth.”

While the Halifax Board members who spoke about the improvement plan at the meeting praised it, they also expressed concerns as to whether it would work.

Board member Donna Hunter discussed the role that absenteeism may play in the ability of schools to improve. On average, Halifax Schools have 261 students out on any particular day.

“It’s a good plan. It’s workable. I believe it will work,” she said. “But it won’t work if the kids are at home watching the ‘Young and the Restless.’”

Board member Susie Lynch-Evans said that many plans have been introduced before to improve academic performance in the district, and for one reason or another, they haven’t been successful.

“They have come to us as the godsend to get these kids where they need to be,” she said, adding later. “I just know what kind of obstacles that we’ve been trying to overcome.”

Battle responded to Lynch-Evans’ concerns at the meeting, saying that she thinks the district can get it done.

“The task is hard, but you will not find a more dedicated team than the people that you have here to get the task done,” she said.

However, Battle did acknowledge during the meeting that there are some problems that are outside the district’s control.

“When we look at the resources and those kinds of things, there are some barriers that we’re having to work around,” she said.

Lynch-Evans also criticized the General Assembly’s change in the definition of a low-performing school. She worried that even if Halifax schools did improve, they wouldn’t get recognition for their progress.

“When we start to make gains, then the legislature comes up and changes the rules,” she said.

She isn’t the only one critical of the changed definition.

Low Performance and School Grades

Not all school districts have a large number of low-performing schools under the new definition. Davidson County, for instance, only has one. But Lory Morrow, superintendent of that district, says the new definition “does not match what is happening” at the school — Silver Valley Elementary.

“…[I]t is important to note that the school made Expected Growth during the 2014-15 academic year and made gains in proficiency as well. A school that makes Expected Growth and increases proficiency demonstrates students are continuously learning and growing. Teachers work hard every day to personalize student learning in order to continue student growth,” she said in an email.

The Guilford County Board of Education also takes issue with the new definition. It passed a resolution calling for state lawmakers to repeal the new definition of low-performing schools and the School Performance Grades.

The press release put out by the district says that there is more emphasis from the state on test scores than student learning, and that schools with high poverty are being treated unfairly.

“Citing multiple studies, the board points out that standardized test scores more closely align with the a [sic] student’s socioeconomic status and race than how much they’ve learned,” the press release stated.

In fact, 80 percent of the grade received by a school comes from academic performance. Only 20 percent comes from academic growth. These grades were instituted by the General Assembly, which also decided the ratio that would make up the grades.

The Guilford release also states that the low performance designation puts serious penalties on schools and could make it more difficult to hire or keep good professionals.

“What this law effectively does is say, if you work in a wealthier school, your job is safe, but if you take on a school and students who face greater challenges, even if you do your job and teach our students as much as they are expected to learn, we’re going to come after you,” says Alan Duncan, chairman of the board of education in the press release. “If you’re one of the best principals or teachers, which job are you going to take? We need to find ways to encourage our most talented educators to teach our highest-need students, not discourage them the way this legislation does.”

Duncan went on to say in the press release that it’s important to know when schools are doing poorly so that they can be improved, but that lawmakers’ actions make that more difficult.

Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools waded into the debate in October. According to the Winston-Salem Journal, the school board passed resolutions opposing some of the requirements triggered by the new definition.

Lawmakers took issue with the school board’s actions and called district officials into the Joint Legislative Commission on Governmental Operations November 18. During the meeting, lawmakers were critical of the board and demanded to know if they really intended to skirt the law.

Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger (R-Rockingham) said he had read the Winston-Salem Journal article, and he asked Superintendent Beverly Emory and district School Board Chair Dana Caudill Jones if they intended to follow the law.

“Is it our intent to comply? Absolutely,” Emory said. “Are there differences in interpretations here? Yes.”

In particular, Emory told lawmakers that the requirement to intervene with principals was problematic because she didn’t think that principals at low-performing schools were failing in all cases. She explained that the district recruited some of its best principals to work at low-performing schools, but that sometimes it takes longer than two years to see progress.

“These may be folks who are really great at what they do,” she said.

At one point, Berger asked the two officials how they thought district students would view their actions.

“Don’t you think it’s important for them to understand that if the law requires them to do something, they should do it?” he asked.

Other lawmakers, like Sen. Bob Rucho (R-Mecklenburg), joined in the questioning. He made clear to the officials how he felt about the district’s actions.

“You are expected to comply with changes to try to improve it because the old way did not work,” he said. “And if you keep trying to do the status quo, at some point this is going to be a problem.”

Stoops says that the the goal of lawmakers who changed the definition isn’t a nefarious one.

“Those who believe that this is a way for legislators to stigmatize or embarrass public schools need to take a deep breath,” he said. “This is nothing more than an effort to fully integrate the school performance grades into the school and district evaluation system.”

But Jeter said the new low performance definitions do have an impact on school reputations. And people won’t necessarily dig beneath the label to understand a school or district in all its complexity.

“I think a lot of people just hit the high notes and move on,” she said.

Rep. Craig Horn (R-Union) said in an email that the new definition is an attempt to give struggling schools the attention they need, but he agrees that the emphasis of the School Performance Grades on “performance” over “growth” is a problem.

“NC schools that languish in the low-performing category certainly need additional attention and resources. Although many of these schools have shown growth, they have not attained a sufficient performance level to allow them to work their way out of the Low Performing School category. Under the current school grading formula, performance is the dominate [sic] factor in the grade earned by each school. As a consequence, those schools that have long been in the Low Performing category are at a significant disadvantage in working their way out of that category for their baseline is so far below the performance threshold necessary.”

Horn says the ratio used to determine the School Performance Grades has to change.

“I think we’re wrongheaded on how we’re doing school grading, insofar as putting the dominant weight on performance rather than growth,” he said in a phone interview.

Until the next legislative session, at least, the current definition of low performing and its emphasis on academic performance is here to stay. In the meantime, schools with the low performance designation have to make improvements. And Horn said in an email that isn’t going to be simple.