Foreward from Johanna Anderson, Executive Director of The Belk Foundation

Since 2013, The Belk Foundation has been focused on early grade reading achievement. Our approach leans heavily on our grantee partners, educators, and experts to guide us toward high impact ways to invest and uphold our mission. Much of our learning in recent years has been understanding the research base, commonly referred to as the “science of reading,” and the ways evidence-based strategies are used in teaching children to read. The body of research is vast, evolving, and highly nuanced. That’s why I was so disheartened to see the recent oversimplified and combative coverage of our state’s momentum related to better applying this research to support reading instruction.

I wanted to write a response to clarify the research, explain why it matters and why we should be hopeful by the collective action in our state towards applying it. As I sat down to write, though, I realized that I’d be repeating a practice I’m trying to confront: not elevating the very experts who are some of our most valuable resources in this work.

Fortunately, three dedicated and knowledgeable experts in reading instruction answered my call to collaborate on a clarification statement on the science of reading. It’s their voices, and the voices of our effective teachers, literacy coaches, school leaders, and faculty, that too often get drowned out in conversations about literacy improvement. I am grateful for their willingness to help present the vast, evolving, and highly nuanced research base in a more digestible way for folks like me. And with that, I pass the pen.

North Carolina, we need a common understanding of what the “science of reading” really means.

In the past week, much has been written and said in reaction to the reference to science of reading in the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021. We’ve heard it called a phonics-based approach, a program, and even the victor in a long-running battle. Let’s be clear: Very few educators in North Carolina are resistant to using rigorous evidence to inform how reading is taught. But there is discomfort among many educators — including educational leaders and researchers — with the way the term “science of reading” has been politicized. Many of us worry that it has been turned into a catchy slogan — a bumper sticker that oversimplifies an immense body of scientific research about one of the most amazing and sophisticated human accomplishments: learning to read.

Learning to read is too important for us to get stymied by politics. Far too much of the discussion so far has misrepresented what the science of reading really offers for improving reading instruction. It’s time to get on the same page. Below, we offer some clarification about the evidence base for teaching reading effectively.

The science of reading is not a narrow program. The science of reading is a vast body of peer-reviewed research from the disciplines of education, psychology, linguistics, and cognitive science, to name a few. The insights emerging from this research are found in numerous publications and reports, including the Educator Practice Guides published by the Institute of Education Sciences. The science of reading is not a program or a simple recipe for how to teach reading. It’s not a product you can purchase in a shiny box. It’s not a name brand or a proper noun. It’s knowledge of how literacy develops that can provide guidance for strengthening student outcomes through a coordinated emphasis on language acquisition, phonological and phonemic awareness, phonics and spelling, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

The science of reading is not just about phonics. An approach rooted in the science of reading supports children in becoming skilled word readers (teaching letters, sounds, and how they come together to make words) and in learning to comprehend text (understand the meaning). Without comprehension, it’s just word calling, not reading. We want to be extremely clear on this point because the position taken by university literacy faculty is often misunderstood or misinterpreted. Acknowledging that phonics operates within a broader arrangement of language and literacy skills is not an anti-phonics position. The evidence is clear that children benefit from systematic, explicit phonics instruction to learn to read words efficiently. Phonics is absolutely necessary, but it alone is not sufficient, and it is not the entirety, or even the preponderance, of the science of reading.

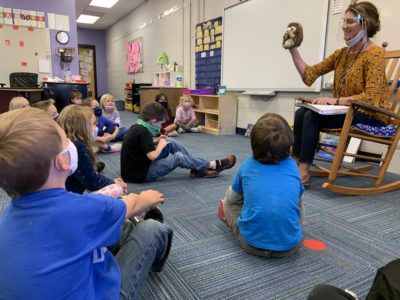

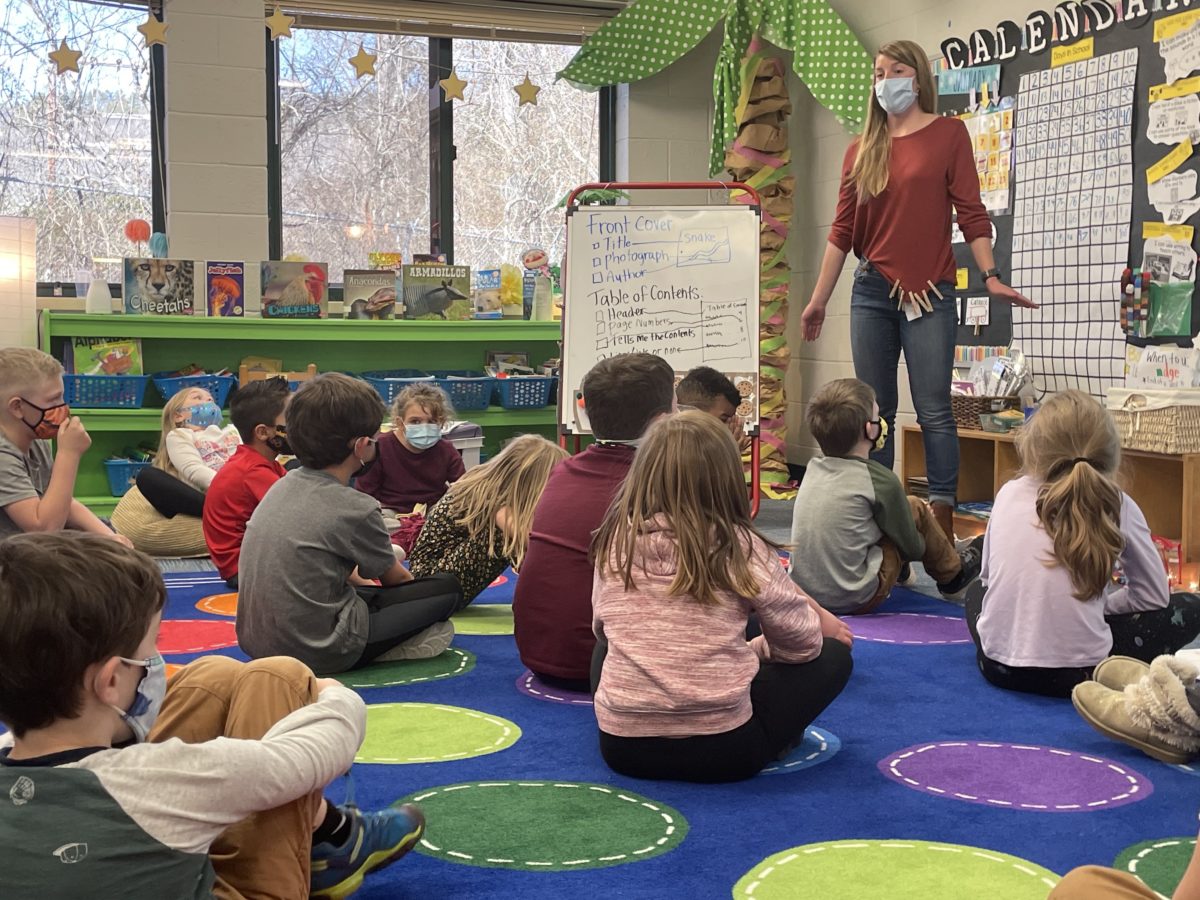

The science of reading does not limit teachers. No student is standard, so no standard approach can reach all students. There is no single science of reading curriculum or program that teachers can follow word-for-word. It doesn’t exist. Teaching kids according to the research requires investing in teachers, building knowledge of how children learn to read and what type of instruction is most effective in the moment for the children in front of them. Part of the difficulty with the current approach in many of our schools is that instruction is overly dependent on the curriculum rather than the teacher. When teachers are smarter than the curricula and programs they use, they can determine how to reach each of their students. An approach grounded in the science of reading puts teachers in charge.

The science of reading does not limit student engagement. An approach grounded in the science of reading depends on student engagement with text. Children have to read more to read better. Children have to want to read to read more. Children need to be exposed to a wide variety of text formats and genres in which they can see themselves and others represented. The science of reading requires classroom libraries rich with authentic, diverse, and engaging literature, as well as informational texts that pique children’s curiosity and build background knowledge.

The science of reading includes writing. Reading and writing are reciprocal processes that develop in tandem. We would not expect an infant or toddler to learn language by only listening and never speaking; we should not expect literacy to develop by only reading and never writing. It’s the exercise of listening and speaking over time that allows for language acquisition. It is no different for literacy development. Writing is a central aspect of the science of reading — though perhaps the nomenclature often makes us forget its critical role in literacy development.

The science of reading is not a magic cure for instant improvements. Just like there is no single science of reading curriculum that teachers can blindly follow, the science of reading is not a “plug and play” set of instructional routines. What science does best is rule out what doesn’t align to evidence, and those practices (like asking children to guess words) should be avoided. Although the evidence base makes a few principles of effective instruction extremely clear (and that’s what we need to make sure teachers know), there are many questions still being examined by researchers about how to best translate these principles into classroom practice.

Over the past several years, school districts and educator preparation programs have been grappling with the reading proficiency of North Carolina children and investigating ways to better support students. At system levels, we’ve had the State Board of Education Task Force on Literacy present a comprehensive set of recommendations, the UNC System Literacy Fellows outline a Framework for Literacy on expectations for preparing teachers to be literacy teachers, and the NC Community College System build their new teacher preparation programs centering on the science of reading. Local school districts across the state are expanding and updating their professional development offerings.

We as a literacy community are actively working to improve the literacy instruction children receive. Declaring that classroom instruction should be aligned to current evidence is a good start, but not the end, of this work. We need to invest in teachers as knowledgeable and capable professionals. We need to provide quality instructional coaching to our teachers as they continue to grow and develop across their careers. These are the investments that will pay dividends for our children and their children. It is not a simple solution — but it is what will work.

Editor’s note: The Belk Foundation supports the work of EducationNC.