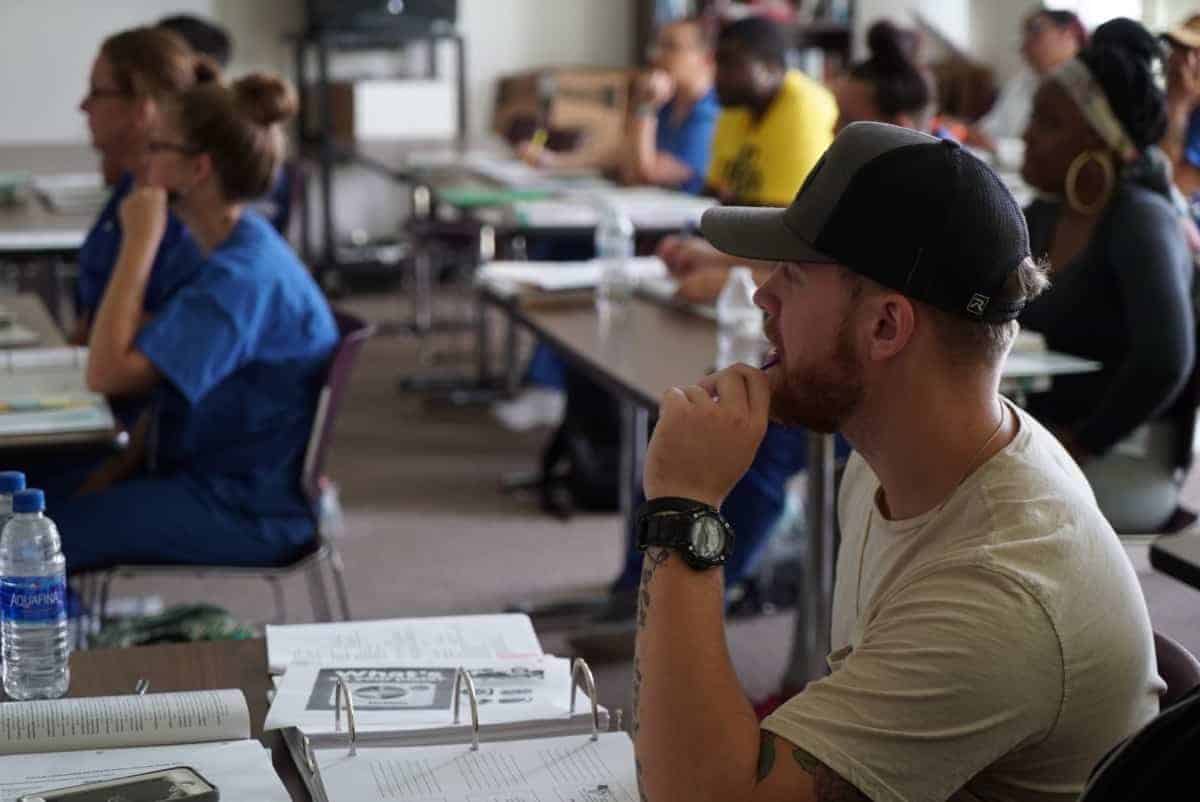

Kelli McKenzie is a student at Haywood Community College.

“I work full time and I go to school full time. I am a mom too – a single mom,” she told us in February.

McKenzie received a hot spot from the college to help her stay on top of her online coursework.

“Before I had a hot spot, I struggled. We live so far out and the internet is spotty that some evenings I would have to go to my aunt’s house and use her internet. And sometimes I would have to do some of my schoolwork while I was at work,” she said.

Over the past year, students like McKenzie have struggled to complete online classes, stay enrolled, and balance the added responsibilities pandemic life threw at them.

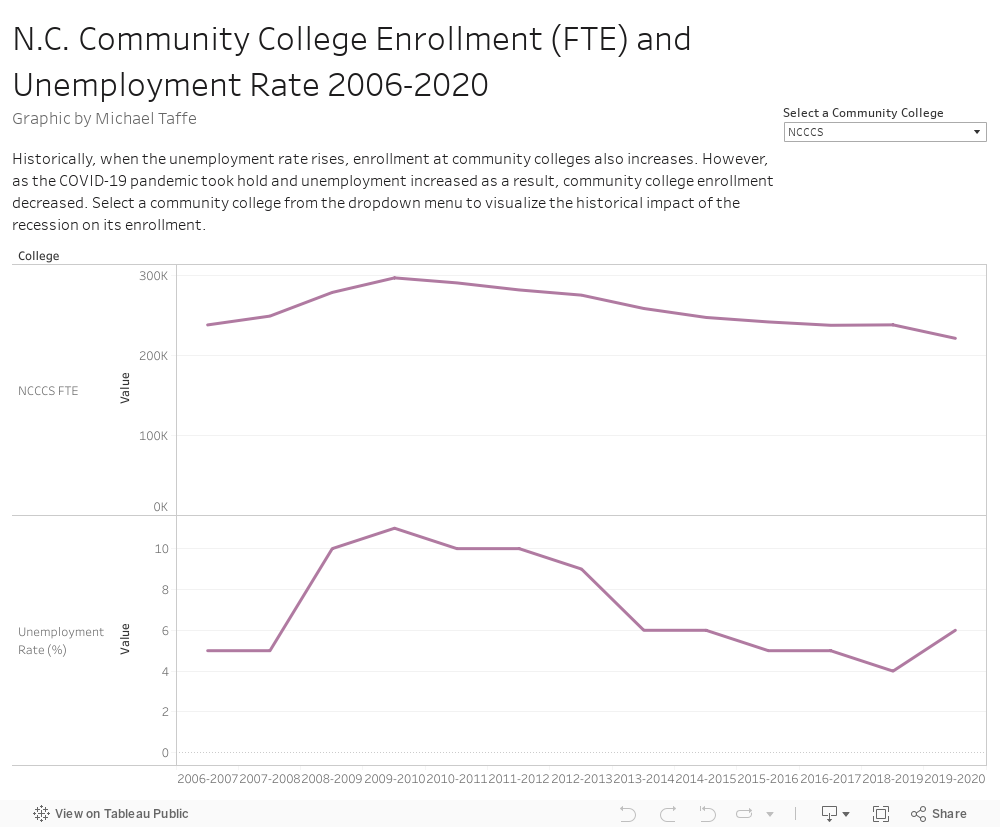

For colleges, that has meant a sharp decline in enrollment this year. Statewide, community college enrollment fell 11% in fall 2020 compared to fall 2019. All but four of the 58 community colleges — Isothermal, Caldwell, Davidson-Davie, and James Sprunt — experienced enrollment declines between fall 2019 and fall 2020.

Enrollment declines were largest among workforce training and basic skills courses: Workforce training dropped 22% from the previous fall and basic skills dropped 51%. Curriculum programs saw a 6% decline from fall 2019.

For many, the enrollment decline came as a surprise. As late as June 2020, state and community college leaders were predicting an increase in enrollment due to the economic downturn from COVID-19. Historically, community colleges have experienced enrollment increases during recessions.

“Any time unemployment takes off, enrollment at community colleges takes off,” said former Sen. Harry Brown, R-Onslow, during a Senate committee last spring.

Use the slider to view year-over-year enrollment changes for the 58 community colleges from 2006-07 to 2019-20. Note the increases in enrollment during the 2007-08 and 2008-09 academic years as the Great Recession took hold.

“This economy doesn’t make sense. It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen before,”

Jason Hurst, president of Cleveland Community College

“You have millions of Americans suffering right now,” Hurst continued, “but it also appears that there are many more that are doing great — enjoying renovations to their homes, buying new cars and new homes. There seems to be quite a bit of disparity among Americans right now.”

Community college leaders say there are several reasons causing enrollment declines.

Select a community college from the dropdown menu to view enrollment changes over the years.

Impacts of COVID-19

Historically, community colleges serve more diverse populations – often those who have traditionally been underserved in all facets, including the education system.

Pre-pandemic, food insecurities were as high as 49% at two-year institutions, compared to 40% at four-year institutions, according to a 2019 report. And rates of housing insecurities among students ranged from 41%-59% at two-year schools, compared to 25%-47% of students at four-year schools. Also pre-pandemic, many students didn’t have internet at home and relied on school facilities to complete coursework.

The pandemic exacerbated these challenges for community college students. Students lost internet access, lost jobs, and had to take care of ailing family members or children now trying to do school at home. For those hit the hardest, many had to make the difficult decision to reduce course loads or press pause on their academic careers.

“Students are balancing teaching at home, having to change hours because of either being laid off or their job responsibilities changed. There are just so many variables in their life that changed, and they couldn’t manage school anymore,” said Hurst.

Fear of the virus is also keeping students away, said John Gossett, president of Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College. Despite colleges putting in safety measures, some students are still choosing not to attend.

“They are hunkering down,” Gossett said.

Broadband challenges remain

Last spring, community colleges moved the overwhelming majority of courses online. While colleges set up systems to distribute devices and hot spots, broadband access continues to be a barrier to enrollment for many students.

“[Students] don’t have access to high speed internet — either they can’t afford it, they can’t get it because of their location, or they don’t have a device at home to access their classes,” Gossett said.

A 2019 report by BroadBandNow showed that only 39% of North Carolinians have access to affordable internet, which they define as $60 per month or less for wired broadband internet.

Adequate devices in the home have also been an issue. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, “Nearly 20% of North Carolina households do not have access to a meaningful device.” For 4.4% of households, a smartphone is the only “computer” that they own.

“Many of our students are parents, and if that child is at home completing their school work, there may only be one computer in the house that now three or four people have to share,” said Gossett.

Not all classes can be taught online

While most programs moved to an online format, some classes just couldn’t be completed entirely online.

Courses that require labs and clinics are difficult to host in an online setting. There are also courses in continuing education, like welding and automotive repair, that have been challenging to move online because they require more hands-on learning.

For the equine program at Martin Community College, online teaching can only go so far.

“I haven’t quite figured out how you can teach breaking a horse virtually,” said Wesley Beddard, president of MCC.

One of the programs that has suffered from not being able to move online is the prison instruction program. The pandemic upended community colleges conducting occupational and basic skills training in prisons, which greatly impacted enrollment numbers.

“You’re going to see a disproportionate decline at colleges that offer prison instruction since there has been no return to the prison since March 2020,” said Dale McInnis, president of Richmond Community College.

According to Brad Deen, communications officer for prisons at the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, “Safety and security needs have taken precedence over in-person instruction.”

Instructors had the option to provide recorded lessons online or upload them to a disc or flash drive if the prison could accommodate that method of learning. Some instructors were able to provide written materials as well, Deen said.

“As we begin to see daylight after a challenging year, we have taken cautious steps toward reopening our facilities to community college personnel,” said Deen. In early March, testing administrators re-entered two prisons, Pamlico Correctional Institution and Swannanoa Correctional Center for Women.

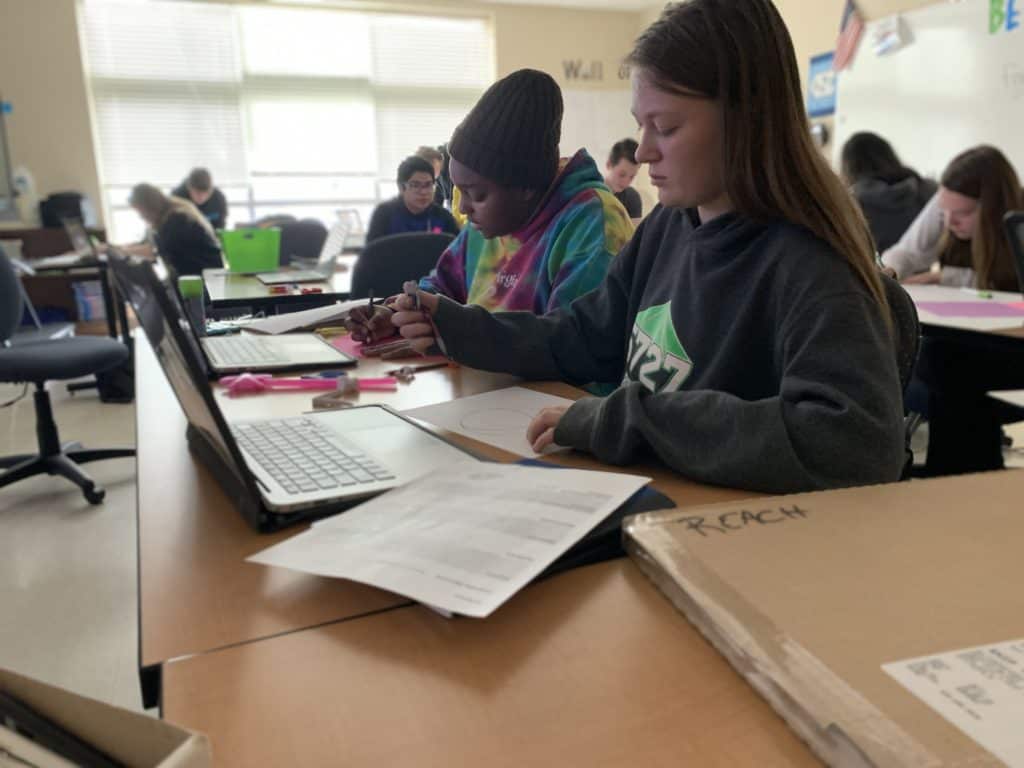

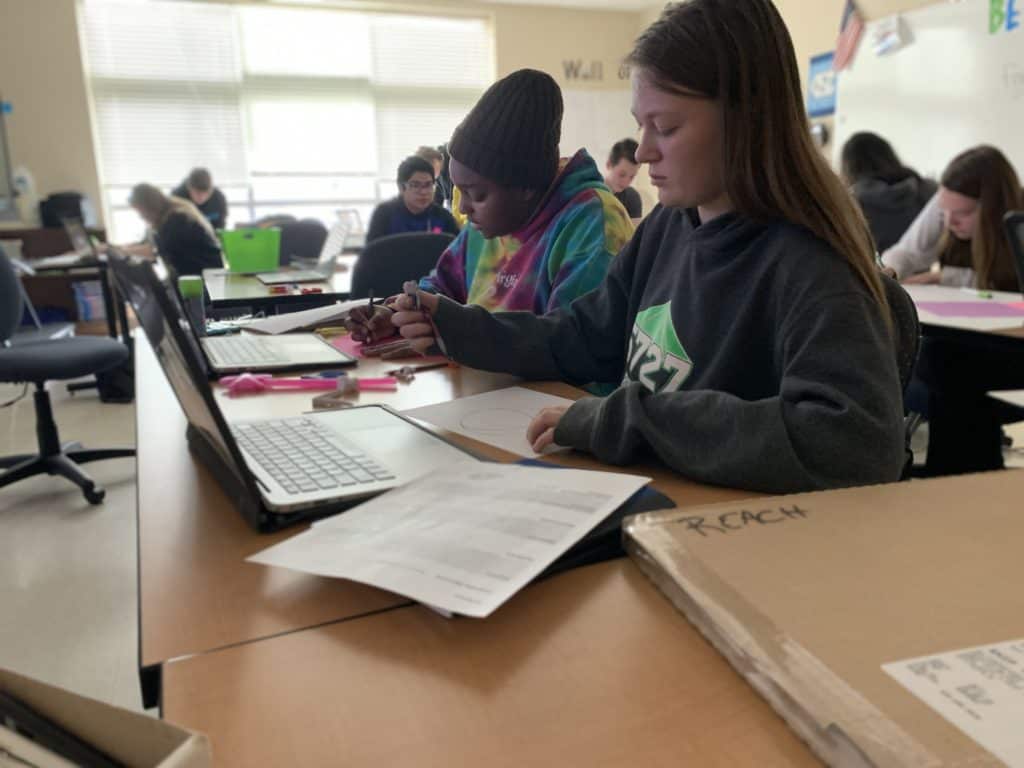

Virtual high school impacts College and Career Promise enrollment

College and Career Promise (CCP) is a program designed for qualified high-school-age students to pursue college classes, tuition free, while in high school. Almost every community college president we spoke with talked about the significant drop in College and Career Promise (CCP) enrollment.

“CCP enrollment was the biggest drop we’ve seen,” McInnis said.

“CCP is all about building relationships, making contact. I’ve got a wonderful team that really understands and cares for students in K-12. Normally they have access to these students and they’re able to go to the high schools and see them personally, and even help build the schedule, but when that personal contact is not available, you really can’t build the structure these kids need,” he continued.

Gossett added, “CCP students enrolling in fall 2020 did not have the same push as they did when they were at the high school taking our classes online, or when they were here on campus. So a lot of work wasn’t getting done, grades were dropping. I would argue the grades were not reflective of the intelligence of those kids, it was more a reflection of time management skills.”

The dropping grades caused concern for colleges’ K-12 partners.

“They realized those grades were less than what they wanted, and they started pulling kids out of CCP to save their high school GPA,” Gossett continued.

The pandemic also seems to have upended students’ plans for the future.

I’ve taught public speaking online to mostly high school students at community colleges for the past five years. One assignment I give to my students asks them to reflect on their past, present, and future.

Since 2020, those speeches have a very different feel to them. When they get to the part about their future, I see concern on their faces. Where I once saw enthusiasm, I now see sadness or uncertainty.

One student used a blank paper with a question mark on it to represent her future because she said she just wasn’t sure anymore. Students used to have a plan for their next steps, whether it be college or a career, but now I am hearing a lot of “ I hope” or “ I am not really sure.”

– Emily Thomas, EdNC policy analyst

Why enrollment matters

Lower enrollments this year could have a significant impact on the number of students that community colleges will credential over the next few years. Ensuring 2 million North Carolinians have a high-quality credential or degree by 2030 — the myFutureNC attainment goal — may prove to be an uphill battle for the state.

“We know that delays in enrollment or the need for individuals to halt their higher education pursuits can decrease the odds that a student will earn a degree or credential,” said Cecilia Holden, CEO and president of myFutureNC.

“With 72,500 fewer students enrolled in our community colleges, we are going to have to see significant increases in years to follow or this year’s declines will translate into fewer graduates with the credentials or degrees needed, further widening the gap that previously existed.”

Cecilia Holden, CEO and president of myFutureNC

Lower enrollment also has a big impact on colleges’ budgets. State funding is the largest single source of funding for North Carolina’s community colleges, and the overwhelming majority of that funding is based on enrollment. Since 2013, state funding has been allocated to colleges based on enrollment from the previous two academic years.

So what happens when enrollment declines? Funding decreases. And when funding decreases, colleges face difficult decisions. For some community colleges, those difficult decisions could mean cutting programs and positions.

The newest COVID-19 relief bill contains $40 billion in funding for colleges and universities. Colleges must use half of the funding for emergency student financial aid grants, but they may use the other half for institutional costs, including lost revenue.

The community college system is also asking for $61 million in non-recurring funds to stabilize their budgets after the steep enrollment declines this year and funding for community college faculty and staff pay raises.

“Federal funds, at this point, have been primarily categorical. The strings on how we can spend it have been fairly restrictive. We can’t use any of that money to increase pay. And if we did, it’ll eventually run out and we’d have to reduce pay,” said Gossett.

“Budget stabilization will help smooth those waters as we come out of COVID and over the next two to three years as the economy begins to even out,” Gossett added.

In a Joint Education Appropriations Committee meeting in February, community college system president Thomas Stith addressed enrollment declines as part of a request for budget stabilization funds.

“Community colleges across the country have been impacted from an enrollment point of view. Our system is not immune to that. While we don’t see some of the same impact as you see across the country, there has been an impact in the state of North Carolina, and it will require support financially as we move forward through recovery,” Stith said.

What does the future hold?

“Educational attainment is the short-term recovery strategy and the long-term resiliency plan for our state’s economy. A better educated North Carolina is the gateway to economic prosperity and upward mobility for all citizens, ” said Holden.

The pandemic has changed higher education as we know it, and North Carolina’s community colleges are taking notes as they think about recruitment and retention efforts for the future.

“Consistently and effectively providing more flexibility for our students will allow our residents whose economic status is most negatively-impacted by the pandemic to get education to assist with entry-level positions, both for those entering the workforce for the first time and also for those whose jobs have gone away and who therefore need to be prepared for different jobs available now and in the future.”

Lisa Chapman, president of Central Carolina Community College

McInnis shifted Richmond Community College’s spring semester start date from January 8 to January 28 to try to stem enrollment losses.

“We had a conversation with our local health director in December,” McInnis said. “They were projecting a post-holiday spike in the virus in our region. The health director said that we were going to have to go online or we were going to have to shift our start date. So we asked for a temporary change to the reporting date,” said McInnis.

The college went from a potential enrollment loss of 13% for the spring semester to a loss of around 4% compared to last year’s spring semester.

At Cleveland Community College, Hurst is discussing a potential pilot program that would allow students the flexibility to take a single class in a variety of formats.

The college would offer a class face-to-face, virtually, and hybrid, letting students choose how they would like to attend the course.

“One week they may take the course online, the next week they may attend in-person,” said Hurst.

Beddard at Martin Community College is laying the groundwork for the college’s first ever admissions office.

The prisons are even exploring the feasibility of online remote learning.

“Last month at Hyde Correctional Institution, 10 students/offenders (free of COVID-19, masked, and socially distanced) began an agribusiness technology course taught off-site and online by a community college instructor,” said Deen.

As colleges begin to map out what education will look like in the future, EdNC will follow along. In future pieces, we will look into the recruitment and retention efforts colleges are implementing this year in response to enrollment declines. Let us know what your college is doing.