Sherry Thomas is working long hours as she moves from conference calls to strategy meetings to webinars to emails to phone calls. The to-do list is long, she says. And it includes staying healthy, because there’s simply no time in her schedule for getting sick.

Thomas is director of the Department of Public Instruction’s Exceptional Children Division, which handles North Carolina’s policy and guidance for special education. Her workload isn’t unique among education leaders during these times — navigating uncharted territory while trying to make the best of the situation.

But as federal guidance boils down to “doing something is better than doing nothing,” Thomas’s task seems, indeed, “exceptional.” Her division serves vulnerable students who have historically had to fight to ensure the “something” they receive is adequate and equitable.

“This is a different problem for us to solve,” Thomas said. “These are our students who are already not used to a teacher standing up and lecturing to them in the course of 90 minutes. These are kids that have more direct, one-on-one and small-group instruction. And so that is more difficult trying to figure that out in a virtual environment.”

Behind the Story

This is the first piece of a two-part report on how the move to remote learning is affecting Exceptional Children. This story focuses on state issues and guidance. The state also is passing information and resources down to districts and charter schools, which are primarily responsible for the standard of remote learning offered to their EC students. In the second story, we’ll see what remote learning for EC students looks like in Cleveland County Schools, and explore some hidden blessings among the challenges.

DPI has a new EC remote learning site

Thirteen categories of kids qualify for special education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Their brains process reading and math differently from what is considered average. Some are deaf, others blind. Children all along the autism spectrum are represented, as are kids with ADHD or emotional challenges.

They are just shy of 204,000 students statewide, according to DPI — mostly in grades K-12 but also including nearly 21,000 kids ages 3 through 5.

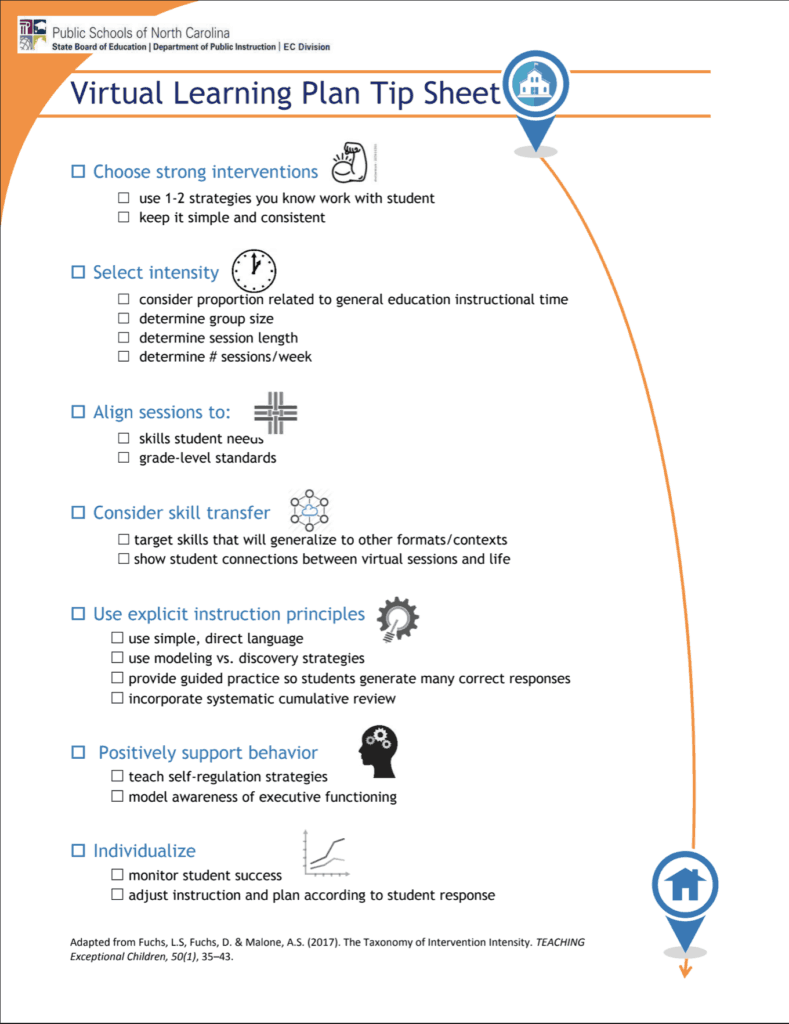

The Exceptional Children Division first released a set of resources to all EC directors at the level of local education agencies. Now a new website featuring EC resources has been released.

In a webinar previewing the new website for EC directors last week, Division Assistant Director Matt Hoskins called for creative solutions. Still, he confessed that instruction aligned to the website’s resources will not necessarily mean compliance with federal laws that guarantee a “free appropriate public education” to students with certain learning differences.

“While these are unprecedented times that pose many challenges for us as we contemplate how to meet the needs of students with disabilities, we also have to think of this as a real opportunity to think creatively in how we can leverage remote learning while remaining accessible and reasonable in light of unique needs of students with disabilities,” Hoskins said.

The resource website will be updated by DPI regularly, the division says. It pulls from resources gathered from the nation’s Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP), Office of Civil Rights and the Department of Health and Human Services, as well as some internally created by the state’s EC Division in collaboration with the state’s Division of Digital Teaching and Learning.

The resources, which the division says have been vetted and reviewed by agency staff, include guidance on virtual Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meetings, evaluations, progress monitoring, and considerations for instructional supports. The site offers curriculum-specific content such as evidence-based virtual literacy and math resources, and also special resources for social-emotional learning, early childhood education and special considerations for those with hearing and visual impairments or significant cognitive disabilities.

“What we have really consistently heard from the US Department of Education and OSEP is that doing something is better than doing nothing, and we’re really taking that to heart,” Hoskins said. “In this case, if we think carefully and collaboratively, we believe in this situation we can do the most good. We may not know the exact, perfect way to do everything, but we can certainly make the effort to do the most good in the given circumstances and to provide, to the best that we can, to students and families during school closures.”

State officials acknowledge that some EC services cannot be offered remotely

While the resources cover a lot of best practices, and are already reviewed for alignment with state standards, there are some issues that remain a challenge with remote instruction. How will the state identify kids who need specially designed instruction? How will it monitor student progress? How will teachers engage these kids online effectively — including those with physical needs and those with attention disorders?

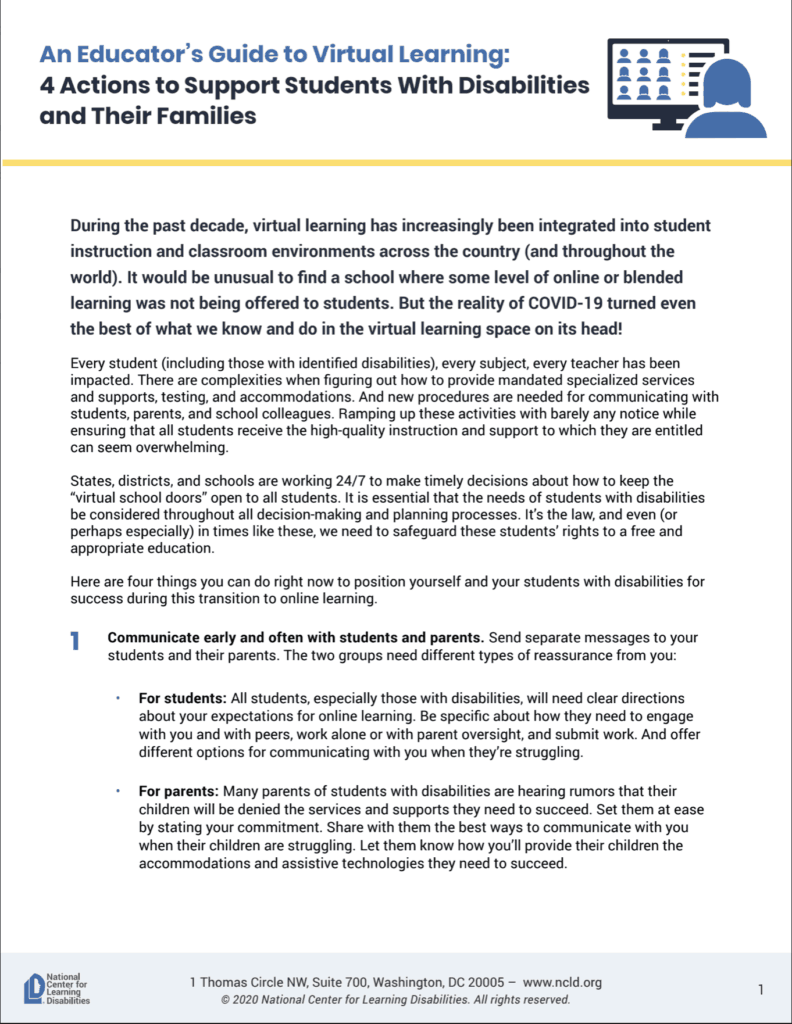

Where IEPs are in place and the IEP team is in agreement with a student’s goals, EC teachers are leaning on the state-provided resources as well as those provided by their districts and some curated on their own. Even some IEP meetings are moving forward either through video conferencing software or by telephone, with draft IEP documents circulated at video conferences or before phone calls.

But across the state — and nationwide — school districts are struggling to figure out how to engage students without access to the internet, how to design temporary instruction when in-school assessments are needed to provide more understanding of a child’s specific needs, and how to fulfill the promises under IEPs or specially designed instruction that are not easily translated to a virtual space.

That’s not to mention doing all of this under federally mandated timelines.

The recently passed Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act gives Education Secretary Betsy DeVos broad authority to waive or loosen standards for compliance with IDEA. And DeVos is hearing from a number of interested parties, including advocacy groups saying that waiver authority for IDEA was unnecessary and a superintendents’ association that says a waiver from special education mandates is vital while schools are struggling to implement new education strategies for all students.

In North Carolina, leaders acknowledge that because of differences in how some of these kids learn, virtual instruction won’t work for some.

“We know, in reality, there are some kids we’re not going to be able to serve, or they’re not going to have access, or parents are so stressed and the kids are so stressed and they’re going to say, ‘We need a little break and then we’ll start back,’” Thomas said. “So we’re trying to be very flexible. I mean, we’ve always had to be flexible, but we’re even more flexible now. And what we’re providing is support and guidance. So as long as districts are making an attempt for each student, providing them with some level of instruction or supplemental instruction, I think that is the best we can do at this very moment.”

The strategy for now is to push out resources from the state agency level to the EC directors and coordinators at each district and charter school. Each local EC director is responsible for executing strategies with the EC teachers under his or her supervision.

Rather then push out information from DPI to a broad audience, Thomas said, the state is operating in this top-down approach in the interest of clarity.

“If a parent reads something and misinterprets the meaning of that, then that creates conflict as far as trying to get that resolved with the teacher, with the principal, with the EC director,” Thomas said. “It really should come from the directors down to the teacher level in every district. That’s how everything else always flows, and we’re trying to keep it in that order. I said early on to my staff, we aren’t changing process or procedures. We are only looking for a different way to deliver all the procedural guidelines we already have in place, and as long as we stay close to our same process, I think we’ll be OK at the end of all this.”

There’s no cure-all; leaders are looking for best-case outcomes

Nellie Aspel is the EC director for Cleveland County Schools. She’s a member representative for the state’s Council of Administrators of Special Education and a regional representative for the Directors’ Advisory Council. She has sat through several webinars and calls about remote learning for special education in the past month. She says that although the situation doesn’t lend itself to an easy fix, the state has acted quickly and responsively.

“I hear lots of praise for the leadership from Raleigh,” she said. “When all of this happened, Sherry immediately got the CASE Board and others together to begin planning. She has had her thumb on the pulse of our state’s special education system during this crisis from day one.

“The Section Chiefs and Regional Consultants have constantly reached out with support and resources. All of them have been responsive … to our questions and concerns. They have given us good technical advice and guidance while at the same time calming our nerves. Over and over we have been told to remember the safety and health of students and staff first.”

Thomas says she knows that in-person schooling won’t be replicated perfectly through virtual instruction. And she’s aware that gaps are emerging, and will continue to emerge, in services that schools can provide to Exceptional Children.

The resources offered are a starting point. Meanwhile, Thomas said, her team is looking for more resources and guidance. If this were a movie or a television sitcom, the story would conclude with the solution tying up all the loose ends and impending gaps in instruction. But that simply isn’t reality right now.

“But our brains are already wired, if you will, on how to do things differently,” Thomas said. “So I have complete faith and confidence in our teachers out in the field that they’re going to find a way to serve their students.”