Words matter.

State education leaders have grappled over the right words to define “high quality reading instruction” for more than five months. Next week, a Department of Public Instruction literacy committee will present a definition to the State Board of Education for adoption.

But the words in the final draft are troubling to some national and local experts. They say the agency’s proposed definition could mean nothing changes in reading instruction across the state.

“There’s nothing in it of substance,” said Barbara Foorman, a national literacy expert who has consulted with the state on improving its approach to reading instruction. “They took out all of the substance. I don’t know why.”

First, a little context

In 2019, the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) convened a B-12 Literacy Committee to examine reading instruction in North Carolina. The department tasked the committee:

“with cross-divisional/cross-area involvement to examine the alignment of policy, legislation, instructional practices, initiatives, and programs to support literacy in NC Public Schools. Subsequently, and in line with the focus to improve student reading proficiency in the early grades, the State Board of Education (SBE) adopted a Collaborative Guiding Framework for Action on Early Reading. … The first action of the framework is to develop a definition of high quality reading instruction that is aligned with the National Reading Panel and current research to guide state policy and practice in reading, from Birth-12th Grade.”

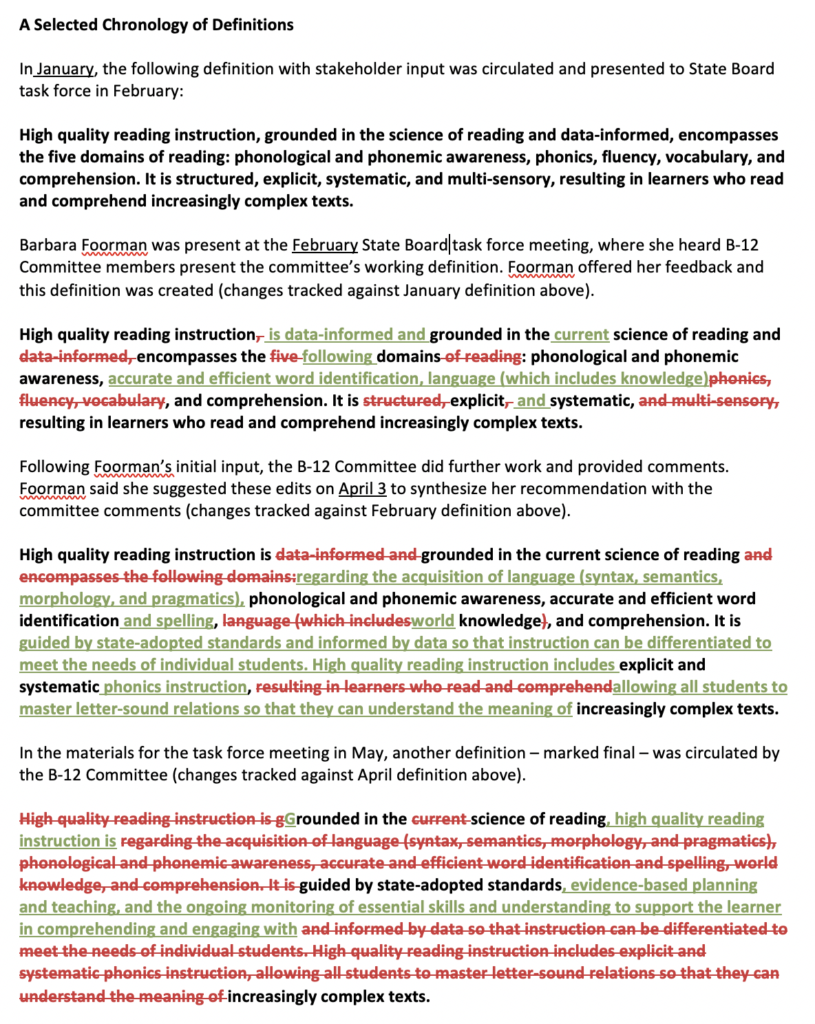

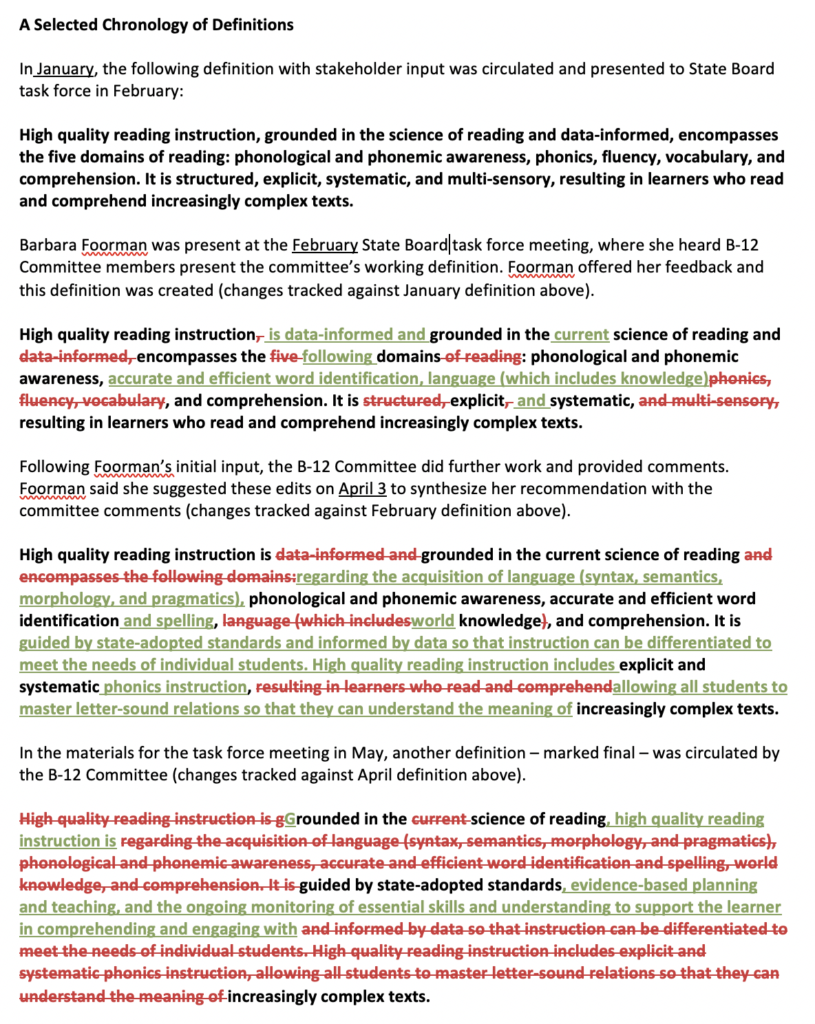

In late 2019 and early 2020, DPI held three regional stakeholder meetings and conducted a survey of more than 1,600 educators to gather feedback on a working definition of high-quality reading instruction. That definition referenced five domains – phonological and phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. These track the domains listed in a 2000 National Reading Panel report.

At about the same time, the State Board established a PreK-12 Literacy Instruction and Teacher Preparation Task Force. The task force membership roster lists Foorman as a consultant.

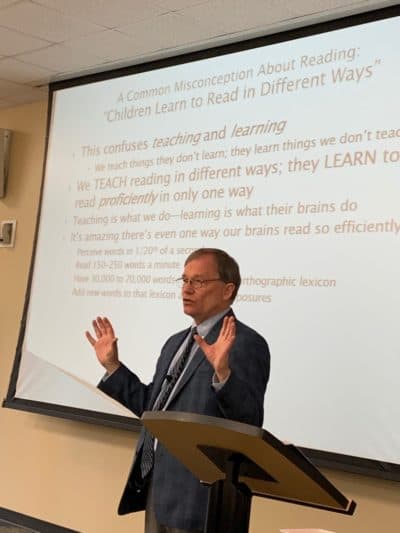

In February, the committee presented its working definition to the task force. Foorman, who contributed to the 2000 National Reading Panel report, was present and provided her feedback.

She said, “we know so much more and have learned much more in the 20 years” since the report. The state should ground its definition in the “current” science of reading, Foorman said, offering a revision to the five domains.

Here is how the proposed definition evolved during the winter and spring:

The committee’s May 2020 update, shared with the task force, includes this proposed definition:

Grounded in the science of reading, high-quality reading instruction is guided by state-adopted standards, evidence-based planning and teaching, and the ongoing monitoring of essential skills and understanding to support the learner in comprehending and engaging with increasingly complex texts.

Concern over the language provided to the State Board

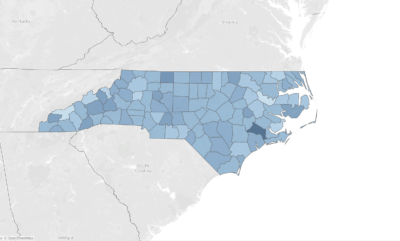

The proposed definition troubles Foorman and Monica Campbell, the literacy department director at Lenoir-Rhyne University’s College of Education. Both say it calls for following the science of reading in name only. In practice, it signals a shift away from making any changes to instruction – a somber thought for many in a state where only 57% of third-graders read proficiently.

“There’s nothing in it of substance,” Foorman said. “They took out all of the substance, and I don’t know why.”

By removing such words as “systematic” and “explicit,” and by deleting mention of specific skills, the definition is overly simplified, Foorman said.

“I think they don’t understand the importance of those domains and how reading instruction should cover them,” Foorman said. “Because there’s solid research – there are meta-analyses, there’s systematic reviews, there are well-designed studies showing how important those domains are. And those studies – the National Reading Panel covered the 20 years prior to 2000, and I’m talking about the research after that, from then until now.”

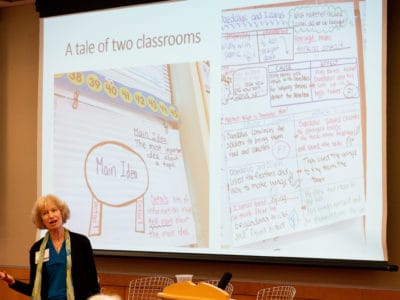

Campbell is also concerned about the definition. A council that scores education prep programs for fidelity to reading science recently acknowledged Campbell’s department as a national model.

Campbell pointed to two ideas retained in the proposed definition – that the science of reading ground instruction and that instruction result in students who can read increasingly complex texts. She said that naming the science of reading means little without any specifics.

“And then, what reading instructors as a community, what we’ve all agreed on — regardless of our philosophy – is that the end goal in reading instruction is comprehending those complex texts which both definitions include,” she said, referring to Foorman’s definition and the proposed definition. “But what’s been so different all along, and what we know from the science and the research and the converging evidence now, is that there are certain things that must be taught – and they must be taught explicitly and systematically.”

“Explicit” and “systematic,” both Foorman and Campbell said, are words that matter.

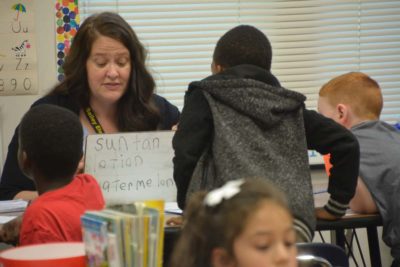

“Explicit” refers to direct instruction from teacher to student about what kids need to know, what it looks like, and how they use that information. It goes beyond a teacher modeling reading practices in front of a class. “Systematic” refers to when different skills are taught, and in what order – an order the research lays out.

“But more importantly, it refers to essential skills,” Campbell said of the proposed definition. “It says, ‘essential skills.’ That’s it. It doesn’t pull out any of what we know those essential skills must be. And those are the things that are included in Foorman’s definition where it talks about the phonological and phonemic awareness, word identification, and language. I love that Foorman included that. The other definition says nothing. I mean, it really says nothing.”

The concern, Foorman and Campbell say, is that the committee’s proposed definition would not require reading instruction across the state to actually change.

“What this would allow to happen is that our state, systems, and schools within our state will continue to adopt these faux [science-based reading research] programs that claim to be aligned with the research,” Campbell said, referring to a white paper recently published titled Whole Language High Jinks. “But they’re camouflaged. So I don’t know how this helps us at all. I don’t know how this definition will help anyone who reads it.”

Dr. David Stegall, DPI’s deputy superintendent of innovation, and Dr. Angie Mullennix, DPI’s director of innovation strategy, did not have time to respond to an email from EdNC seeking comment prior to publication because of the pandemic.

In an email in the evening on May 22, Stegall wrote, “The state board consulted with Dr. Foorman for the literacy task force as a consultant. The state board did not ask any specific individual to write the definition, but instead asked the consultant to help facilitate the discussions, give insight and provide support. The definition received feedback from the field after each iteration – which included reading teachers, higher ed literacy professors, school administrators and others.”

Why the definition matters

The State Board does not intend for the definition to mandate specific instructional practices. However, State Board of Education member JB Buxton said it is a centering point for specific policies and practices.

“The goal of having a definition is that it’s the anchor,” Buxton said. “It’s the anchor for all the professional development, for the way in which districts are doing work, for what we say to universities about what we want to characterize their preparation (of pre-service teachers) or their professional development, for what vendors ought to be offering. It just becomes a clear anchor for all the work we do around early literacy, so we’re all on the same page, speaking the same language, focused on the same things.”

Foorman said the current language in the committee’s proposal would be a poor anchor if the goal is to align reading instruction with the scientific research. The task force, which will make its recommendations at the June board meeting, will use Foorman’s definition.

“What we have to keep going back to is the fact that so many students in our state are not readers; they are not reading at a proficient level,” Campbell said. “And that is not OK. I mean, that has, you know, lifelong impacts on the individuals, and it perpetuates so many cycles.”

In other words, the words in the definition matter.

“I really worry about our state,” Campbell said. “I really am worried about what’s going to happen to the students that are impacted by some of these things.”