When Nickey Stamey was diagnosed with breast cancer, she was comforted by the way her community in western North Carolina rushed to help. After Jeff Howell lost his mother, a lifelong educator, he was inspired when the local Smart Start partnership named a literacy program in her honor. And as collective tragedy from COVID-19’s health and economic impacts hits every corner of the state, personal connections are strengthening this rural community’s response.

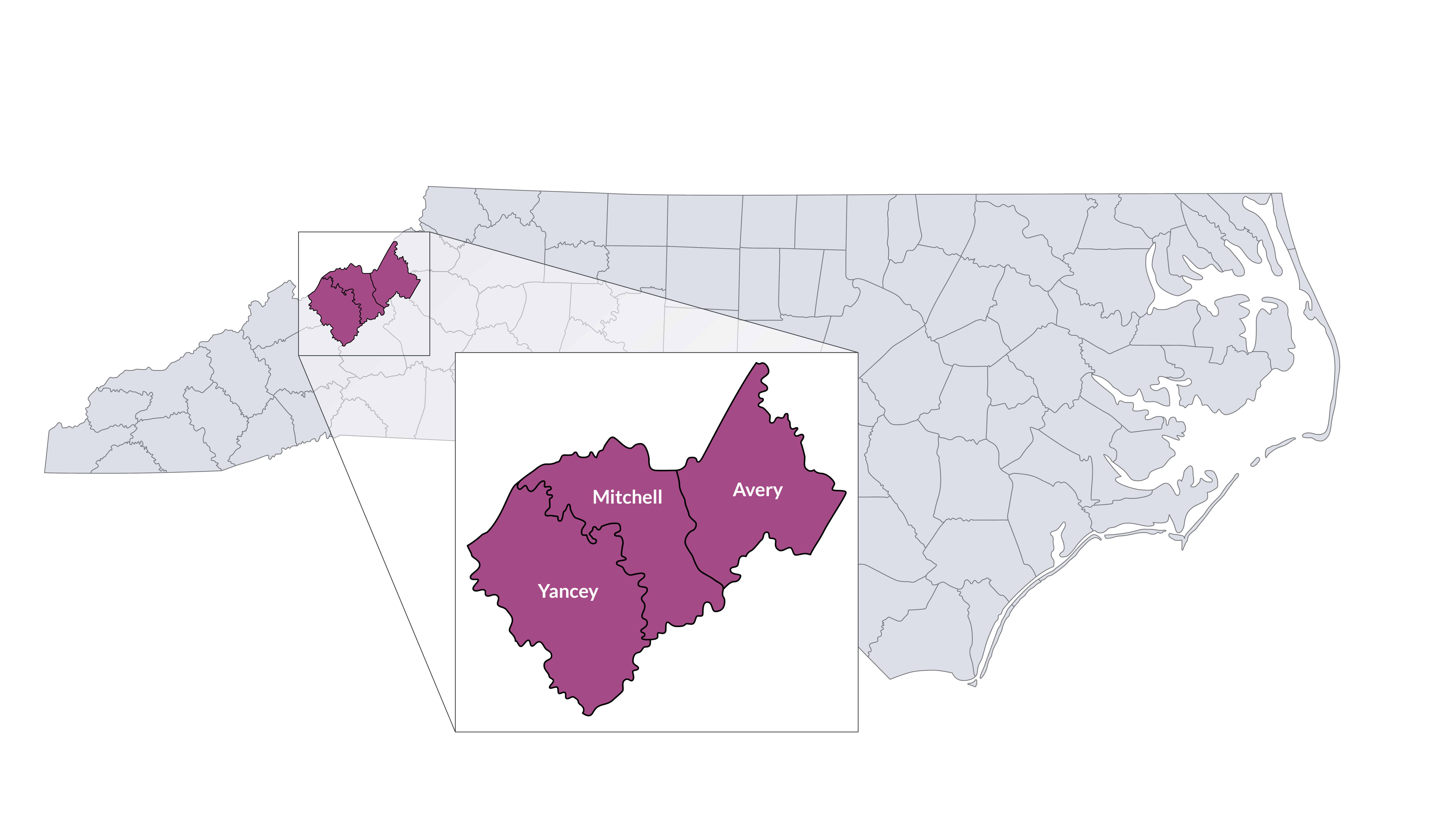

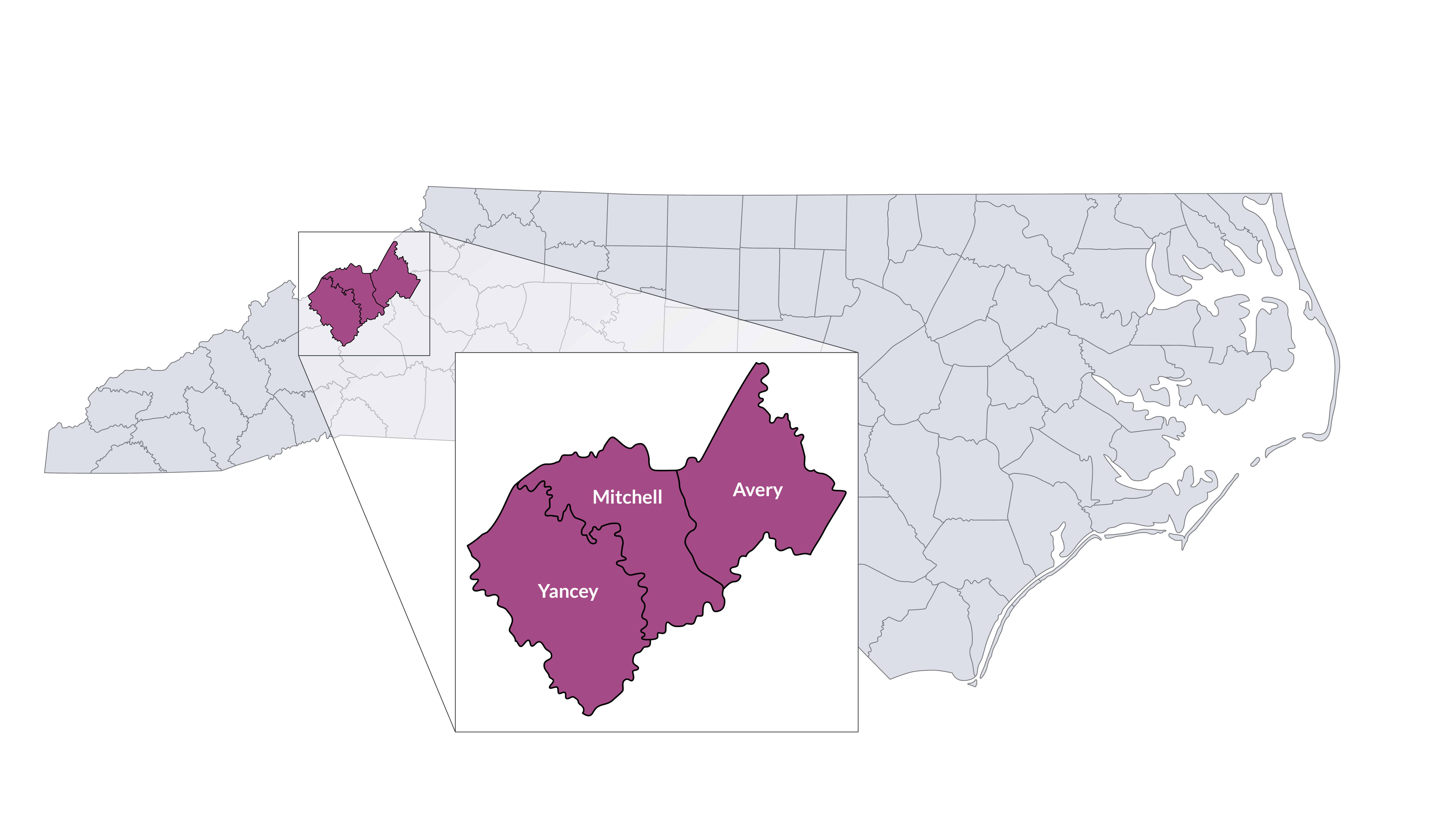

“Us little counties in the western part of the state, we get some pretty amazing things accomplished,” said Stamey, the director of Blue Ridge Healthy Families, a home-visiting program that promotes healthy early childhood experiences for families in Yancey, Mitchell, and Avery counties. “I’m always in awe of the mobilization, and not just, you know, in these huge instances.”

As state leaders issue orders and guidelines on how families and systems should navigate the pandemic, it’s hyperlocal coordination that has kept this corner of western North Carolina connected and resilient. In many ways, the early care and education community has been at the heart of that coordination.

“It’s one of the joys and true pleasures of living in a small town,” said Jennifer Simpson, director of the Blue Ridge Partnership for Children, part of the statewide Smart Start network of 75 local partnerships that provide resources and support for child care centers and families. The Blue Ridge partnership serves that same three-county region in northwestern North Carolina.

Simpson is in regular contact with local leaders from health care, corrections facilities, and emergency management agencies. Her organization keeps track of which child care centers have available slots for essential workers, and is coordinating a child care plan in case coronavirus cases pop up in the area.

Her staff breaks down the available child care slots by location and age group, and Simpson shares the information with leaders of hospitals, emergency management facilities and prisons in case their employees need child care.

She said the demand for child care has leveled out as workers settle into their routines and most people stay home with their children. As of Monday, there were no confirmed COVID-19 cases in Avery and Yancey counties, and Mitchell County had five. No COVID-related deaths had been reported in the three-county region.

But if an outbreak does come, more child care needs would appear, Simpson said. She has been identifying specific centers that have staff willing to work flexible hours. Through a grant from Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, Simpson has also secured extra pay for child care workers who continue to care for children despite health risks and low compensation.

“We’re just wanting to get all of those plans in place so if they do have to move to that surge level, we can be prepared within 24 hours to make that available to those families,” Simpson said.

When all this started more than a month ago, Simpson said, she wanted to do what she could to take some work from the overwhelmed emergency management agency. Like Smart Start partnerships throughout the state, the organization has become the point of contact when child care centers need supplies, such as food or cleaning materials.

“Being a part of the Smart Start as a statewide initiative, you can’t help but compare resources that are available in a larger community versus resources that aren’t available — but what we do have is the relationships and the connections,” she said.

‘Mind-boggling’ impacts

That’s how her friendship with Howell, Yancey County’s emergency services director, came into play. When Howell’s mother passed away in 2017, Simpson changed the organization’s Dolly Parton Imagination Library to “Mary Lou’s Imagination Library.” Howell said his mother’s family and friends raised several thousand dollars in her honor. “It’s because we built that trusting relationship that we’re able to have those really frank conversations,” Simpson said.

Howell has coordinated responses for all types of disaster: ice and snow storms, tornados, hurricanes. “This is a disaster like no other disaster,” Howell said. “There’s so many different factors when you’re throwing in not just the pandemic — the economic impact, the educational impact — it’s mind-boggling. And nobody knows really when it’s going to end.”

Howell said he is sure there are COVID-19 cases in Yancey and nearby counties that just have not been confirmed. With limited tests, he said, the county is only keeping track of people who are part of essential workforces or in serious conditions.

The economic toll may be larger in his county than the health toll, Howell said.

Charlene Ray, a Yancey County native and mother of four, is hoping her work will come back soon. She said she was surprised when her job as an in-home aide for elderly people was not considered essential.

“I’ve been out since March 11. I really don’t know when I’ll be able to go back because we’re waiting on the school announcement,” Ray said on Thursday. On Friday, Gov. Cooper announced schools will be closed for the rest of the school year.

Feeding neighbors

Ray said the community’s support has reduced some stress. The school system delivers meals daily for each of her four children — who are 1, 3, 9, and 15 years old.

Katherine Savage, program coordinator for the Blue Ridge partnership, worked with the public school system to ensure their food deliveries would provide meals for younger children as well. Savage is working with the local Head Start program and with Stamey to stay in touch with families with young children and know their needs.

Savage said the coordination in food services has been made possible by a food council that started meeting last November.

“We actually have a food hub which is pretty darn amazing for a small county,” Savage said. She pointed to such council members as the Reconciliation House, a Christian food ministry, and Dig In, a community garden with a food relief mission. As Savage has tried to locally source child care centers’ menus, she got involved with the council.

“It was clear to us that we weren’t going to solve this with just a grant, that we had to come together as a system of people providing food,” Savage said.

With relationships already in place, Savage said the cross-agency collaboration came naturally in the past month.

Savage said the region still has a lot of work to do to fix problems the pandemic has made more clear.

“The frailties in our food systems are making themselves known,” she said.

“Even though we’re in emergency mode, we’re beginning to see what’s going to be needed long-term to be able to create a reliable food system.”

Home visiting as “a bridge”

Besides receiving meals, Ray, who participates in Stamey’s home visiting program, said a case worker dropped off a laundry basket of cleaning supplies, toilet paper, diapers, and other items that are hard to find in stores at the moment.

“Through all this, they’ve been amazing,” Ray said. Since her husband is still working, she said, going to the store with all of her children has been a struggle. She said some stores are limiting the number of people per shopping cart, so bringing all four of her children has not been feasible.

Stamey said her program has been able to stay in touch virtually with the 40 families it serves — sometimes with fewer distractions than normal visits, yet sometimes with less of the intimacy that in-person contact provides. The program is buying tablets with three months of data to ensure families have internet access to stay connected.

Stamey said the program is based on a national model called Healthy Families America for child abuse and neglect prevention and mitigation. According to the program’s website, the model “is the primary home visiting model best equipped to work with families who may have histories of trauma, intimate partner violence, mental health and/or substance abuse issues.”

Most families are referred to the program through people or such agencies as the Department of Social Services, an OBGYN facility, or the local health department. The program works with families prenatally through the first three years of children’s lives, focusing on nurturing attachment between parents and their children.

In a crisis like this one, Stamey said, the program’s case workers are families’ connection to whatever resources they may need.

“Home visiting is filling a huge gap for families,” Stamey said. “A bridge, really.”

Stamey said families need as many “bridges” to the outside world as possible right now. The program’s case managers have been helping families “identify their circle of support,” she said.

Stamey said some parents are struggling with depression in isolation, some are worried about taking their babies in public to shop, and others are facing challenges with home-schooling.

At the same time, she said, many of the families the program serves already struggle with a lot of the issues others are facing for the first time — such as unemployment and food and housing insecurity. This crisis has taken away some shame from those challenges, she said.

“I see families reaching out more and not feeling bad about reaching out like they may have otherwise,” Stamey said. “The crisis has normalized the need for help.”

Ray, who said she is a “go with the flow” kind of person, remains positive. She spoke on the food services coordination in the county, the support from her home visiting case manager, the surprising way her children have adjusted to new routines.

“I didn’t expect it to go well for any of us, but it has been working out,” Ray said. “We just pray that God helps us through it, I guess.”