Share this story

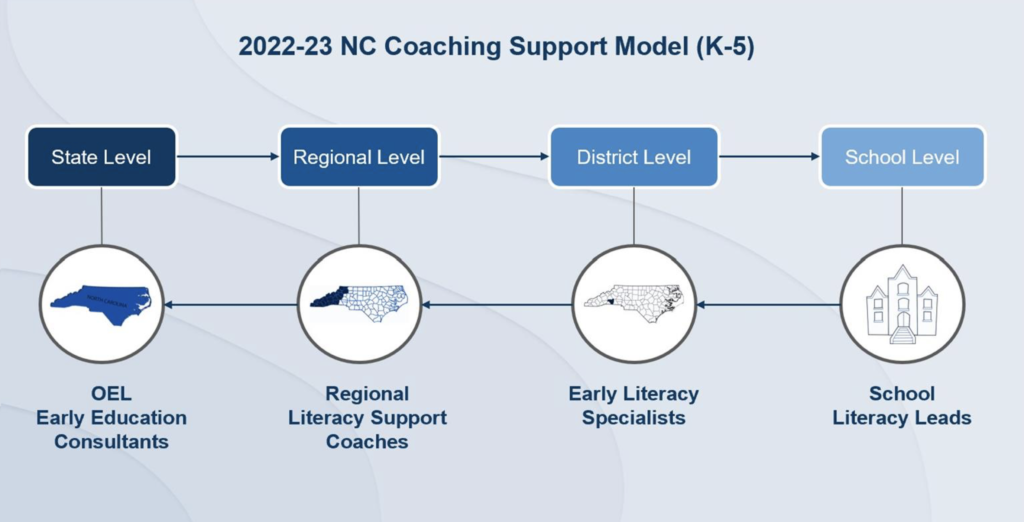

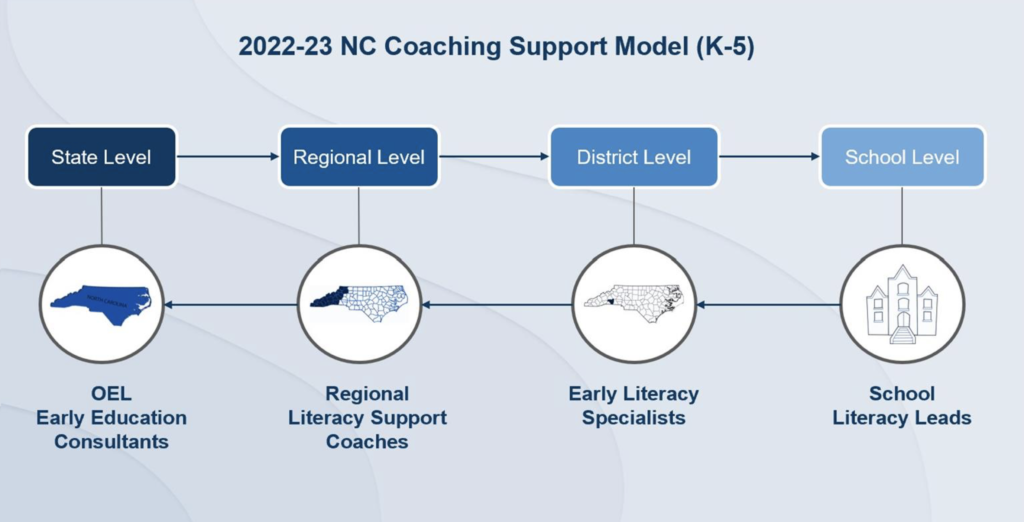

- The Department of Public Instruction unveiled a statewide literacy coaching model that would include hiring 115 new district literacy specialists and two new regional literacy support coaches. #nced

- The plan would bolster state regional literacy supports and put literacy specialists in each district. #nced

The Department of Public Instruction (DPI) unveiled a statewide literacy coaching model that would include hiring 115 new district literacy specialists and two new regional literacy support coaches.

DPI designed the model, officials said, to build capacity in schools to help teachers convert knowledge from literacy training into instructional practice. The coaching plan would also benefit roughly half of the highest-needs schools in the state, DPI said on Thursday.

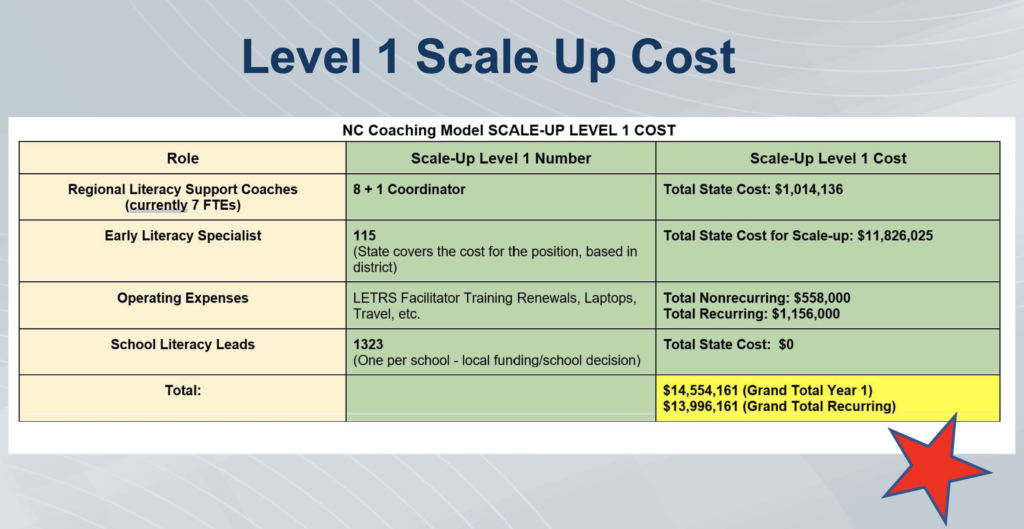

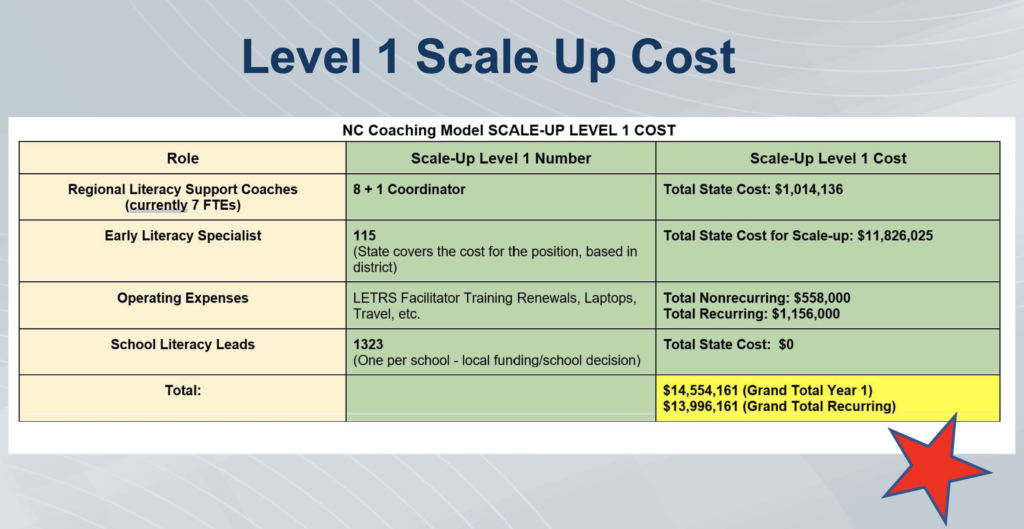

The plan, co-presented to the State Board of Education by Office of Early Learning Director Amy Rhyne and District and Regional Support Director Cynthia Martin, is contingent upon a legislative ask of $14 million in recurring funds. The General Assembly will consider the proposal when it gavels in its short session on May 18. The bill-filing deadline for the short session is Monday.

The model, Rhyne said, would provide each district with an early literacy specialist who would work with the district’s designated literacy team or “literacy lead” — a designation each district submitted to DPI when Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) training began last year.

The early literacy specialists will work with DPI and the district to support the aligned implementation of science of reading, while also providing support to coaches in schools identified as low performing.

“This will allow every district to have high-quality representative to attend virtual or in-person meetings, monthly, led by the Office of Early Learning as we continue to provide ongoing supports and resources for aligned and effective district and school implementation practices,” Rhyne said.

Why coaching — and why district-level instead of school-based?

Rhyne began her presentation to the State Board by stressing the importance of coaching in translating theoretical knowledge gained from professional development and training into sound classroom instructional practices.

The notion is based on research dating back to the 1980s conducted by researchers Bruce Joyce and Beverly Showers. That research addresses the advantages of bolstering a teacher’s theoretical learning with modeling, practice, and coaching. However, much of this research is based on studies that observed school-based coaching — meaning coaches working directly with teachers in the classroom.

Mississippi used that approach when it showed significant progress in reading proficiency from 2013-2019.

Rhyne said Mississippi’s model wouldn’t translate directly to North Carolina, which has nearly 500 more elementary schools and nearly twice as many schools designated as low-performing. In Mississippi, the state hired, trained, and deployed school-based literacy coaches — but it placed these coaches only in schools designated as “low-performing.”

Rhyne said it would cost $133 million to place coaches in every elementary school. While DPI’s proposal declines to do this, Rhyne said she hopes it still provides broader support than models that don’t provide support in every district.

Martin, whose office would receive eight turnaround coaches if the joint DPI and State Board legislative asks are granted, said some of the 115 early literacy specialists could also support schools designated as low-performing by the state.

Rhyne said DPI would look for coaches with skills to support teachers in both literacy and school turnaround, and place them in those districts that may already have strong literacy coaching supports in most schools.

That would leave early literacy specialists with bandwidth to also help with turnaround coaching at the classroom level. Martin said these low-performing schools would still need district- and principal-level support.

Coaching proposal changed based on feedback

Initially, Rhyne said, her team developed a model based on existing funding. Without enough existing funding to provide each district with a literacy specialist, the original plan was to ask districts to add this role onto the plate of an existing educator.

DPI changed course and asked the General Assembly for funding support after discussions with several different stakeholder groups — a network of twelve districts that were farthest along in science of reading implementation, district chief academic officers, superintendent and principal representatives, and a group of state and national literacy experts.

These stakeholder groups worried about the inequities that would arise in coaching support if the positions depended on local funding.

“One superintendent said … ‘Are we going to repave the road or are we going to build a new road?'” Rhyne recalled. “Right now, we’re building a new road. So as we’re building this, we need to make sure the right pieces are in place.”

The coaching model is the latest in DPI’s efforts to implement the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021, passed last year to align pre-K through fifth-grade instruction with the body of research called the science of reading. The law provides for a four-year implementation schedule, with the state now beginning year two.

So far, much of the public attention has focused on LETRS training. However, the law also contains mandates for educator preparation to ensure future teachers graduating from state institutions of higher learning are trained in scientific reading research. It also asks that DPI provide literacy instruction standards — or science-aligned practices mapped onto the existing English Language Arts standards course of study — as well as feedback on district literacy intervention plans.

The law also requires DPI to create a model literacy implementation plan to guide districts in choosing curriculum. It does not require DPI to provide a list of approved curriculum, as some states like Tennessee and Colorado have done in their efforts to align instruction with the science of reading.