Recently the education news waves have been dominated by talk of the impending class size crisis. Across the state, school districts are facing awful choices: cutting arts, PE, and foreign language classes, swelling numbers at 4th grade and above to 40+ students, and holding classes in hallways in order to comply with an unrealistic law quietly inserted into the state budget in 2016.

When public outcry first began over the legislative changes, some state legislators acknowledged the law’s shortsightedness. House Education Committee Chair Craig Horn admitted the mandate was not “fully thought through with regard to unintended consequences.”

But with the quality of our public education at stake, how does a law like this get passed in the first place? And what can be done to prevent it from happening in the future?

With many education professionals right down the road at the Department of Public Instruction and thousands more experienced teachers in the field, every piece of education legislation should be thoroughly and systematically informed by best educational practices in order to yield optimal outcomes for our students. Unfortunately, North Carolina’s General Assembly has a pattern dating back to when Democrats were in power of fast tracking major education initiatives by placing them as special provisions in the budget to avoid the public debate and stakeholder input so vital to the creation of effective policy.

The current class size crisis may be the most recent example of what can happen when a legislature fails to listen to educators, but it’s hardly the first.

The literacy program Read to Achieve — created five years ago — suffered from the same malady. When Read to Achieve was passed in 2012, the legislation was intended to end social promotion and help 3rd graders avoid what Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger has called the “economic death sentence” awaiting students who are unable to read proficiently. According to the legislation,

The goal of the State is to ensure that every student read at or above grade level by the end of third grade and continue to progress in reading proficiency so that he or she can read, comprehend, integrate, and apply complex texts needed for secondary education and career success.

Berger’s intentions may have been laudable, but it’s clear that Read to Achieve’s implementation lacks the educator’s touch. The initiative attempted to improve reading by increasing the volume of assessment in grades K-3 and ratcheting up the threats of retention, essentially punishing children for not being able to read well enough in early grades. That’s not the approach an effective teacher would take. A good educator works to understand where the child is coming from and develop unique supports that best fit his or her individual circumstances. A good educator knows that punitive measures seldom result in long term success.

According to former NC superintendent Dr. June Atkinson, when Read to Achieve was drafted, the Department of Instruction was very candid about the challenges it presented and the impact it would have. DPI warned the General Assembly that the volume of portfolio assessments the legislation added to 3rd grade was too high and that the pace and funding of implementation didn’t provide enough professional development for teachers to effectively transition to the new system. The General Assembly had also slashed pre-K funding 25 percent from pre-recession levels at the time, and DPI informed legislators that quality early childhood education was an important component of building a foundation for literacy. All of that feedback fell largely on deaf ears.

Data from a comprehensive 2014 UNCG study on the first year of Read to Achieve reveals that the program struggled mightily from the beginning as a result of state lawmakers disregarding the advice of education professionals. The survey included responses from 66 district superintendents, 729 elementary principals, and more than 3,000 elementary teachers. Respondents said that “educator input should have been more systematically and extensively sought in the design of the RtA components and statewide rollout,” and indicated a need for more flexibility in using state funds for reading interventions. Eighty percent of K-2 teachers and 93 percent of 3rd grade teachers felt that Read to Achieve had “resulted in a significant loss of instructional time.” Perhaps most concerning of all, teachers reported the number and intensity of assessments were “negatively impacting some students’ attitudes toward reading and their enjoyment of teaching.”

UNCG’s report detailed educator’s feelings about the first year of Read to Achieve, and anecdotal information I collected from elementary teachers in various parts of the state suggests that little has changed. Teachers still report that students and educators alike are overwhelmed by the number of assessments and that Read to Achieve’s inflexible requirements are reducing time spent on other important topics such as writing instruction. As one teacher put it, “We spend so much time testing that we honestly just don’t have the time to teach. If a student doesn’t do well then there is no time to go back and reteach, but instead hope that they have time to tutor after school.” Schools still lack money to be able to provide more reading specialists to work intensively with struggling readers. Pre-K funding has improved slightly, but quality early education is still out of reach for many of our families.

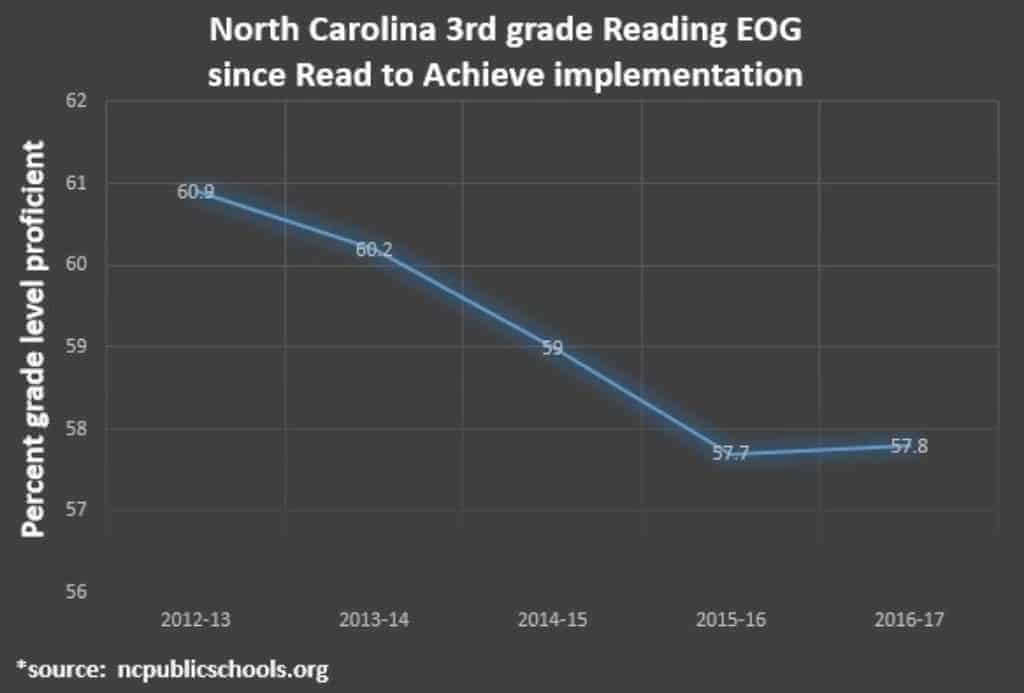

If Senator Phil Berger’s goal was to improve 3rd grade reading, Read to Achieve does not appear to be working. Since the law was passed in 2012, the number of our state’s 3rd graders reading on grade level has actually dropped 3.1 percent:

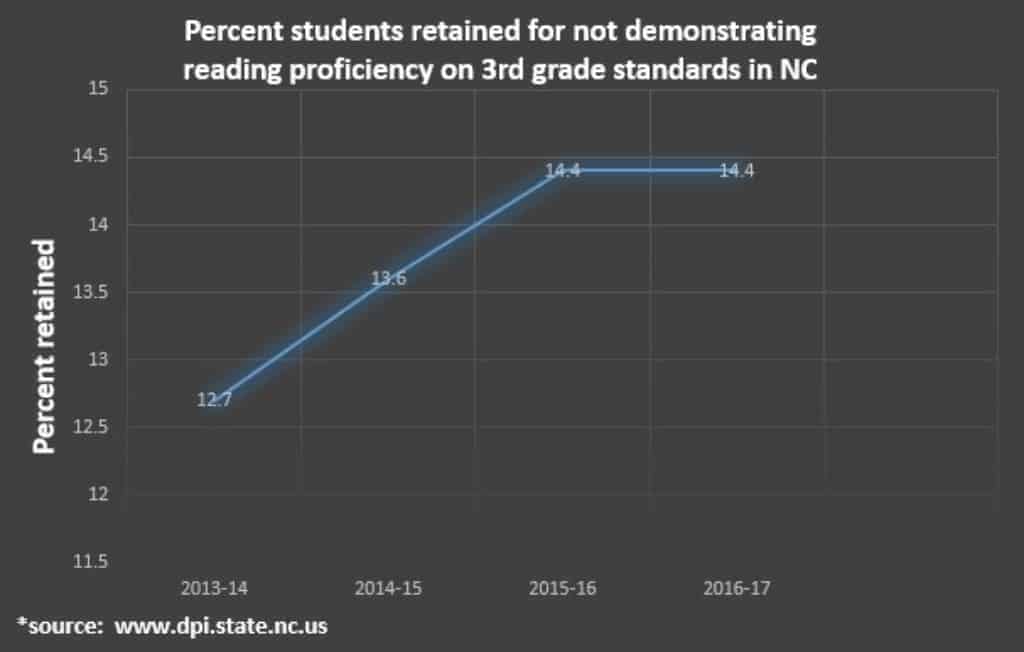

In addition, the number of students retained for not demonstrating reading proficiency on third-grade standards has risen each year since Read to Achieve was implemented, except for last school year when it remained flat. For clarification, students retained do not necessarily repeat the grade but are retained in a third grade accelerated class, placed in a transition class with a retained label, or placed in a fourth grade accelerated class with a retained reading label.

Had the General Assembly truly partnered with the Department of Instruction on improving early grades reading, the results might have been very different. Legislators could have provided the requested high-quality pre-K for more students, allowing them to enter kindergarten with a stronger foundation on which to build. They could have given instructional flexibility to districts rather than burying students from Franklin to Currituck under piles of inauthentic assessments that sap student motivation. If our leaders had been willing to allocate the resources, the law could have provided additional reading specialists and given existing teachers the professional development they need to find new, engaging strategies for supporting our struggling readers. Regrettably, that’s not what happened.

As the saying goes, those who don’t learn from the past are doomed to repeat it. Despite clear evidence that dismissing the advice of professional educators leads to poor results for our students, the General Assembly is continuing that pattern today. What starts out as a decent idea and effective campaign flyer bullet point ends up causing major damage because of poorly informed execution.

In 2016, lawmakers inserted a major class size reduction for grades K-3 into the state budget and passed it with little debate and no funding. Just like with Read to Achieve, the intention behind class size reduction was not the problem — no educator or parent would argue against smaller teacher-student ratios. The major flaw of this legislation was in the execution, in the idea that such an improvement could be had for free with no adverse side effects.

Then-Superintendent Atkinson reports there was minimal discussion between the General Assembly and the Department of Public Instruction prior to the creation of the class size law — a shocking fact given how this legislation stood to change the landscape of our schools. The collaboration was limited largely to the department providing legislators with comprehensive data. The Department of Instruction also reportedly informed the General Assembly that reducing class size was a huge mistake without sufficient dollars, specifically explaining the consequences for North Carolina’s schools if the law was passed but not funded.

After the class size reduction passed, public outrage quickly grew as parents, school officials and teachers became aware of the reality they faced. While our lawmakers waste valuable time alternating between blaming school districts for the crisis and assuring the public there is no need for alarm, 1.5 million students and more than 180,000 staff watch our state inch ever closer to crisis. Parents are faced with the reality of children with no exposure to arts and PE classes so crucial to nurturing creative minds and healthy bodies. Teachers at grades 4 and above are wondering how they’ll be able to teach such large numbers of students — and whether they’ll have to do so in hallways or closets because of the lack of sufficient classrooms.

All over North Carolina, budgets are due to county commissions on May 15, and preparations must begin in earnest for next school year, with year-round schools set to start classes in early July. The most frustrating part of this mess is that it could have been prevented if the General Assembly had chosen to work with the Department of Instruction to set attainable goals on class sizes.

So where do we go from here?

How do we cultivate productive partnerships between educators and legislators so that the laws that impact so many of our children are informed by the experience and perspective that can make them more effective?

Imagine how different things could be if we developed a process for authentic dialogue between the classroom and the General Assembly. Picture a gathering of teachers and legislators in the same room — not for a photo op, but for real talk about specific problems and solutions in our schools. Such convenings could be by facilitated by groups like the Hope Street Group or the Public School Forum, organizations with access to networks of teachers who are eager to engage with policymakers if that interaction can lead to better policy.

A legislator with an education bill in the draft phase could participate in a roundtable discussion with teachers who have experience directly relevant to that particular bill, everything from early grades reading to dropout prevention. Convenings could occur in person initially, then virtually as the bill moves through the process. Another idea could be to create a teacher advisory body that checks in regularly with members of education committees in both the House and the Senate as laws make their way through the committees, helping to ensure their work takes into account best practices and the reality of the classroom. This meaningful collaboration would improve the quality of our legislation and build a valuable bridge between two groups that have been throwing stones at each other instead of working together for far too long.

Teachers, do you have any additional ideas on what more effective partnerships with lawmakers might look like?

Members of the General Assembly, are you open to the possibility of developing a closer working relationship with educators?

The short session is right around the corner. Springtime in North Carolina would be a great time to renew our commitment to trying to do better for our children