There is a slide inside the Durham Public Schools report on suspensions that I suppose is meant to reassure folks.

Ninety-two percent of DPS students received no suspensions last school year, it says, even as districtwide suspensions jumped to 5,552, reversing three years of declines.

It’s good context, but a few days after attending a three-hour workshop in Chapel Hill I’m not sure how much it matters.

The workshop, “Measuring Racial Equity: A groundwater approach,” is one that many community members in Durham and Chapel Hill have taken. I was among about 200 people, mostly white, at the Kehillah synagogue Sunday afternoon.

The workshop started with a fish metaphor. I don’t know what it is about fish. There’s the feminist bumper sticker “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.” And of course, the saying “If you give a man a fish …”

This metaphor started with dead fish.

If you had a fish tank and one day you found one of the fish floating belly up, you’d probably ask ‘What’s wrong with that fish?”

But if, say, half the fish turned up dead, you’d probably start asking, “What’s wrong with the water?”

As news media cover the schools, or crime and policing, or affordable housing, we do this fish thing. We tend to focus on problems without looking at the underlying conditions that cause … well, all of them.

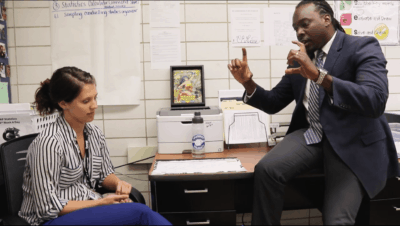

The workshop trainers, Deena Hayes-Greene and Bayard Love of the Greensboro-based Racial Equity Institute, said we even have different words that keep us from seeing the connections. In schools, we talk about the achievement gap. In health care, we talk about disparities. In child welfare we talk about disproportionality. Or we use language to camouflage. Whose “mass incarceration” is it anyway? (Hint: There is no “mass” white incarceration in this country.)

“It’s all different language, but it all means the same thing,” Love said. “It’s just racial inequity manifested in different systems.”

And as long as we talk – and by extension report – about the impact of race on one social system at a time, on schools, or health care or policing, or housing, he added, “we will not see racism for what it really is.”

So what does this have to with suspensions?

I spoke with reporter Zachery Eanes about this Monday night, the weekend workshop still fresh on my mind. A report I’d heard on WUNC that day said we’re at 4 percent unemployment, some think heading toward 3 percent. And I asked Zach how that could be, and of course it’s partly because the one number that gets reported doesn’t include those who’ve given up looking or who are working part time and can’t find full-time work.

And I thought about the suspensions, and how only 8 percent of DPS students got them. And I wondered, because suspensions can take kids out of school, how many suspended kids fall behind, drop out and never find full-time work that pays a living wage. Even a small percentage means hundreds a year, some of whom won’t get counted in those unemployment stats. Are we creating not just a permanent underclass, but an invisible underclass?

Yes, we can’t let one or two misbehaving students interrupt a classroom, but what is misbehaving anyway? And if we think of kids like fish, is the misbehaving kid the problem or the signal it’s time to change the water?

“The thing about white advantage,” Love told us, “is you don’t have to see it to get it; you just do.”

I know this is obvious to some of you. And likely that others stopped reading at the dead fish.

“People say everything’s about race,” co-facilitator Hayes-Greene acknowledged. “Well, it is.”

But if white people don’t think race matters, they should think again, the trainers said, because focusing on gaps and disparities – how people of color are doing compared to white people – just keeps the focus off how much better we all could be doing if those connected systems, if the water in the fish tank, was healthier and more just for everyone.

So that’s one of our challenges in 2018, as we continue to reinvent the newspaper: To look for connections, to find people working toward solutions, to seek out those whose life experiences and knowledge are missing from our stories.

Because until we do that, we’re all missing out.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in The Herald Sun and has been posted with the author’s permission.