In 585 BC, the Central Asian Medes and Lydians fought the Battle of Halys. In 1919, Sir Arthur Eddington proved Einstein’s theory of relativity. In 1979, I was born. And on August 21, 2017, teachers from around the state gathered at the North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching.

What do all these things have in common? A total solar eclipse.

In 585 BC, a solar eclipse ended the 15 year war between the Lydians and the Medes. The sight stunned the battling armies and led them to lay down their weapons.

In 1919, Eddington was able to show, using an eclipse, that gravity can warp light, proving a portion of Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

In 1979, while I was a bump in my mother’s belly, portions of the United States experienced a total solar eclipse.

And today, another total solar eclipse appeared over parts of North Carolina and elsewhere in the country.

NCCAT hosted a program called, “Once in a Lifetime: Astronomy and Experiencing the Total Solar Eclipse” for teachers from around the state. The goal was both to prepare them for witnessing the event, and instructing them on how they could use the eclipse to teach science in their classrooms.

In the morning before the eclipse, Jake Evans of Morehead Planetarium and Michelle Benigno of North Carolina State University’s Science House taught the teachers what they could expect during the eclipse, how they could stay safe, and what they might see.

“Remember, you have less than two minutes of totality,” Evans told the teachers, reminding them that they needed to take the time to appreciate the experience. Don’t take photos, he said. Just soak up what nature offers.

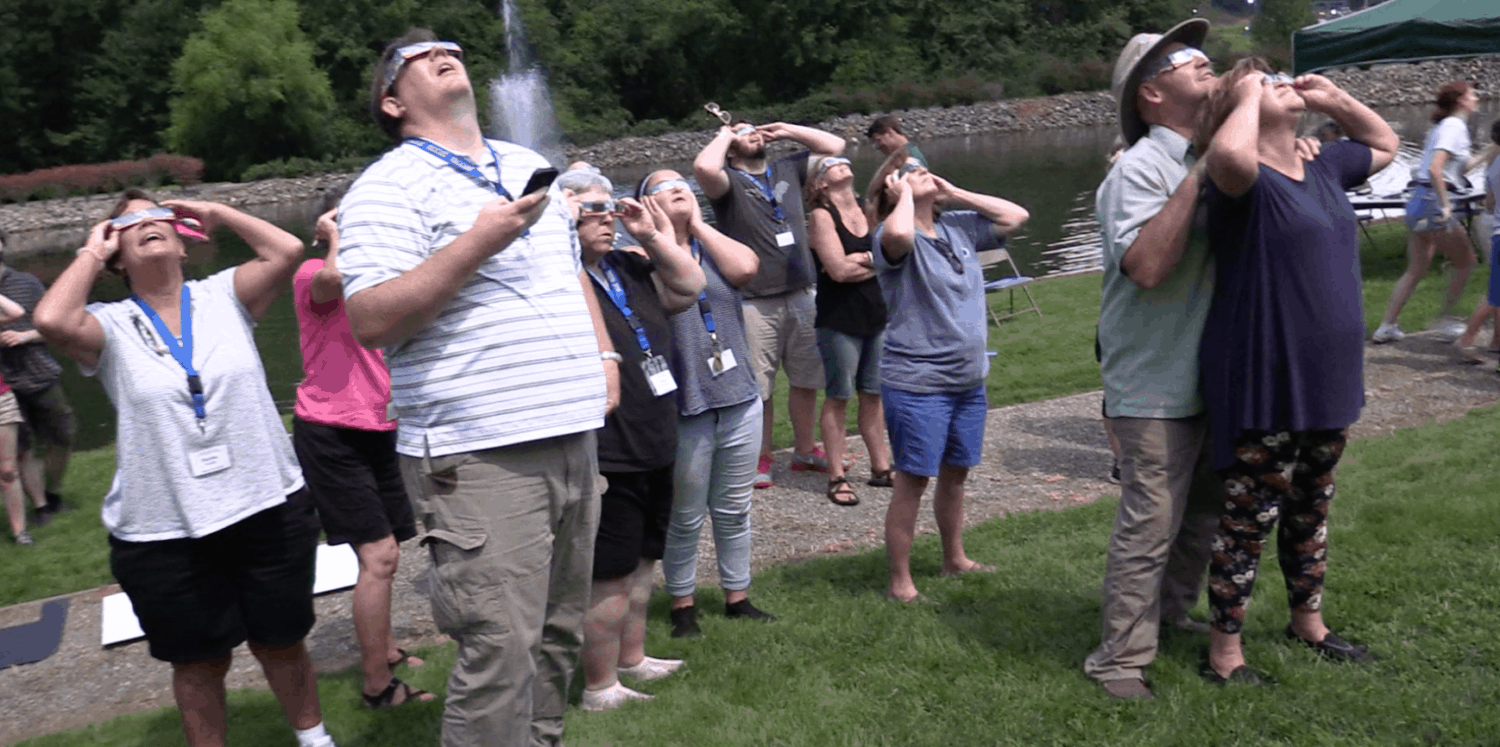

There was a lot of talk about the danger of looking directly at the sun. Evans taught the teachers the best way to put on and take off eclipse glasses was to look away from the sun when doing so.

Teachers concerned about the safety issues were assuaged when Evans told them that men ages 16 to 20 were the most likely to be injured during an eclipse thanks to their tendency to throw caution to the wind. “Shocker,” he said.

During the moment of totality, when the moon completely covers the sun, Evans explained to the teachers that then, and only then, could they take their eclipse glasses off. He also explained that as soon as the moment of totality passed, they had to put their glasses back on.

Some teachers were worried that they would not get their glasses back on in time. Benigno said there was an app that would tell them audibly when to take their glasses off and put them back on.

“I really don’t want you to worry. And you know what we’re going to do?” she asked. “We’re going to broadcast it over three speakers while we’re outside.”

Today’s eclipse was the first visible one in the United States since 1979. The path of totality — the path where the total solar eclipse can be viewed — was a line that nearly divided the United States in half. Only certain parts of the Tar Heel state fell within the zone of totality.

Tracey Reason, a first grade teacher at Williamston Primary in Martin County, said she knew that she would only get a partial eclipse in eastern North Carolina and wanted to come to the path of totality.

“I knew we were going to get a lot of valuable information, it was going to be a lot of fun to do it because I’ve been to NCAAT before, and I know how they…made things exciting, and I wanted to get a lot of information for my students.”

Before the big event, the teachers learned about things they could see during the eclipse — the strange behavior of animals, a ringlike sunset visible in the horizon, a decrease in temperature, and more. They could use this knowledge to teach science in the classrooms.

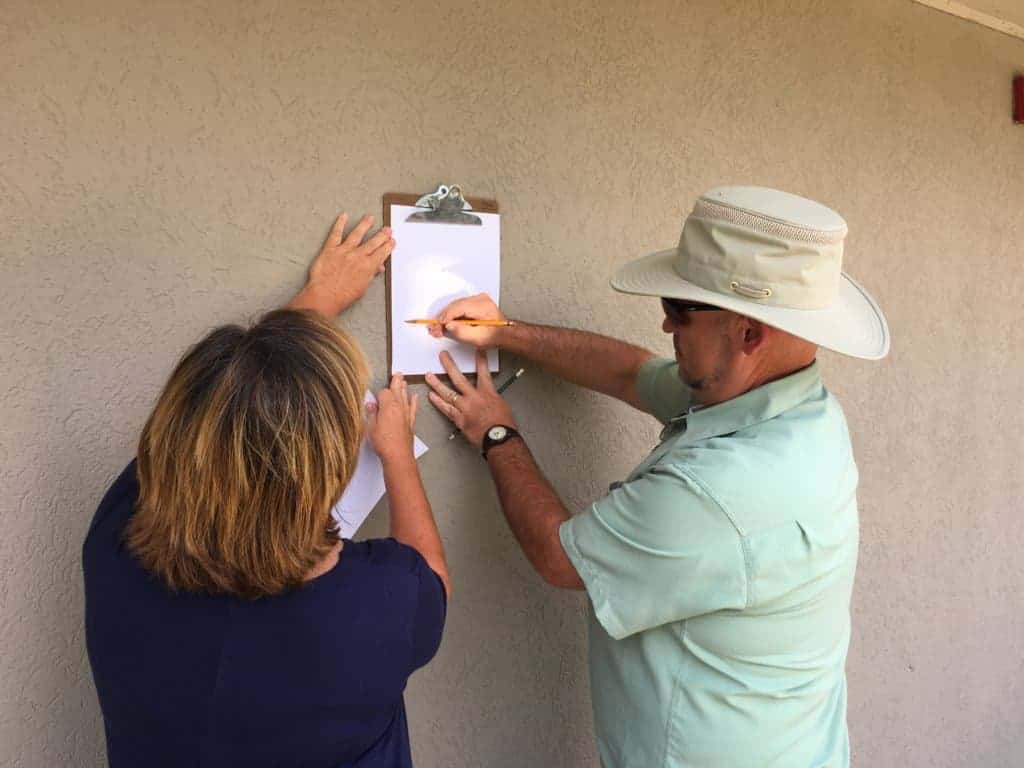

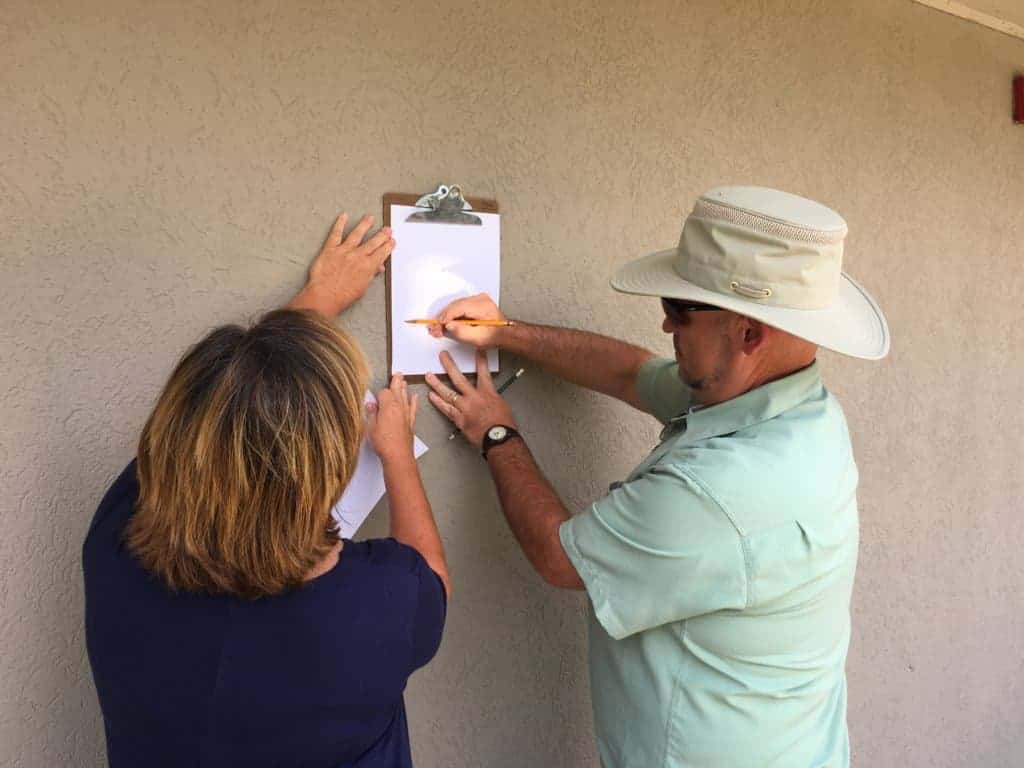

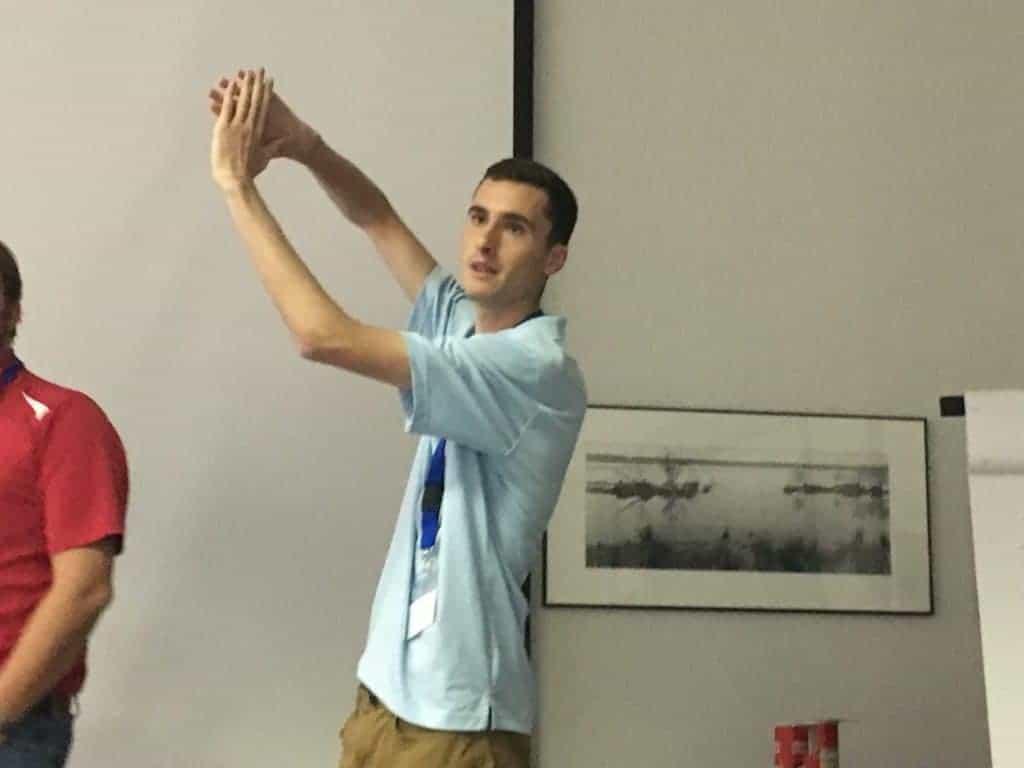

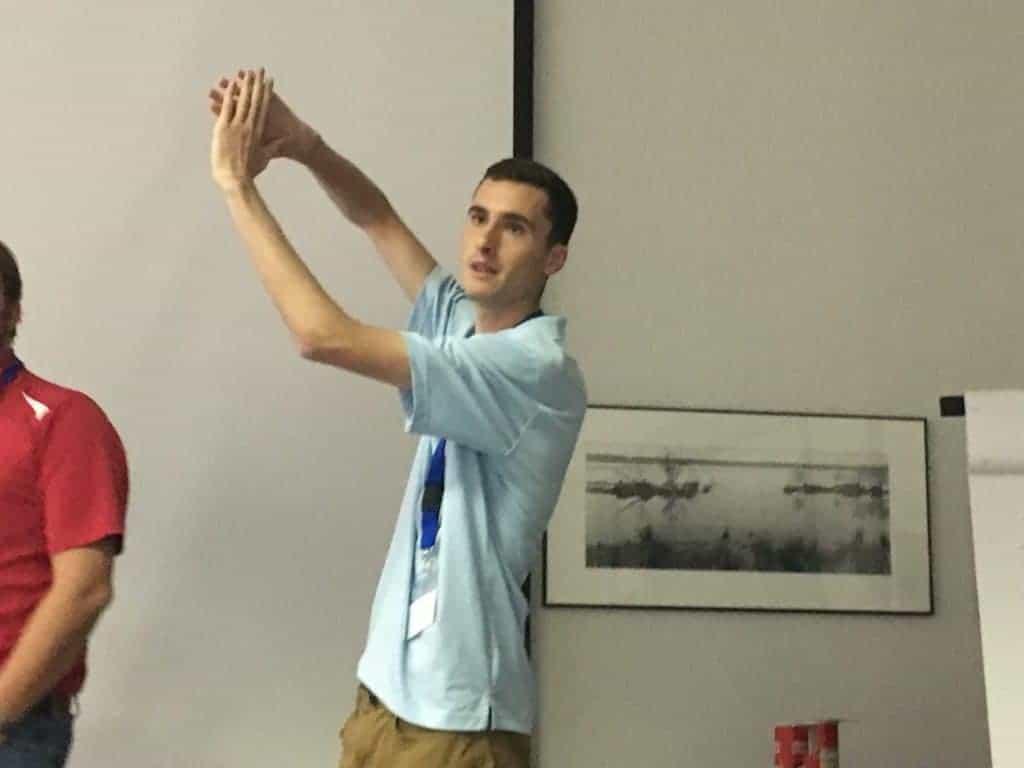

They made pinhole cameras which can be used to project an image of the sun onto a flat surface. This is one way to view the eclipse without glasses. A hole is poked in an object, like the bottom of an empty Pringles can, and the sun shining through the hole will put an image of the sun on the ground underneath it. During an eclipse, the globe will appear as a crescent. You can also do the same thing by meshing your hands together.

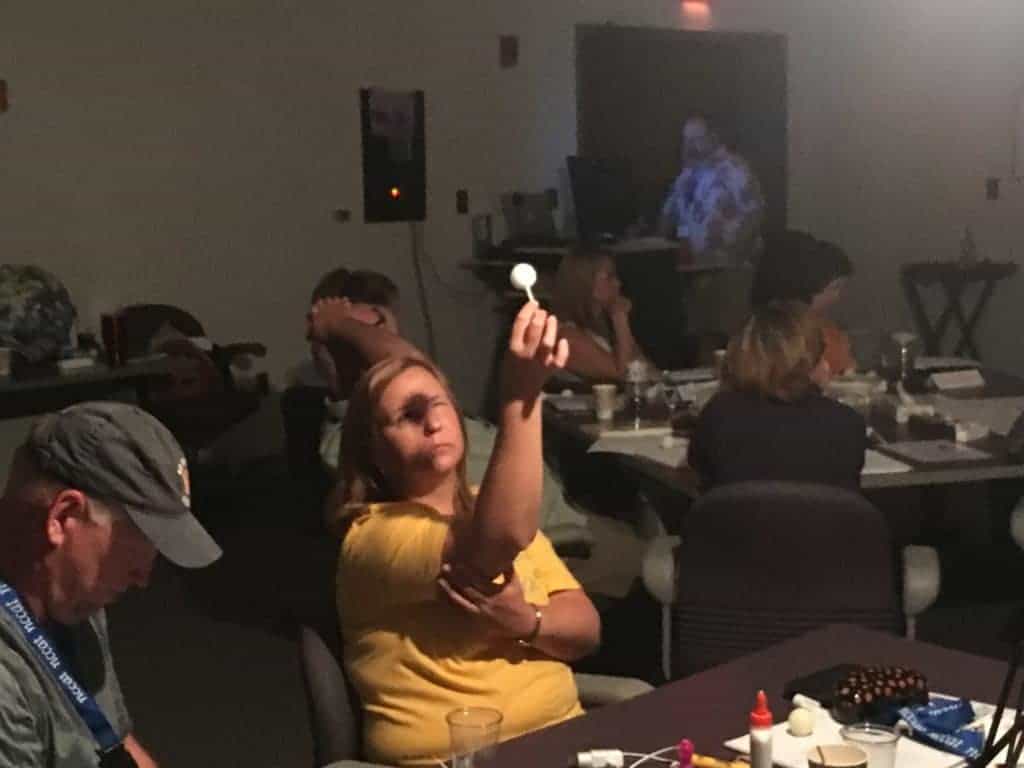

Teachers learned about a phenomenon called Baily’s beads where, as the moon covers the sun, little beads of sunlight appear around the edge of the moon. They duplicated this effect in a room in NCCAT by using ping pong balls and a light bulb.

Parts of the instruction also included some of those stories mentioned earlier: the proving of the theory of relativity, the Battle of Halys, and the discovery of Helium — which also happened thanks to a solar eclipse.

Teachers were given articles explaining these stories and shown how they can have students explain the facts they read in the story, communicate what the information in the story means, and instruct the students on how to understand the significance of what they’re reading.

Tanya Scott, a sixth grade science and social studies teacher at Newport Middle School in Carteret County, was one of the teachers attending the event. When asked why she came, she replied, “To see one of the best viewing spots around,” she said. “It’s just a great opportunity.”

She said she hopes being there will help her teach about eclipses more authoritatively in the classroom.

“I think with anything, being able to have a first-hand experience in something, your kids sense your excitement in something,” she said.

Chris Campbell, a middle school science content coach for Durham Public Schools, was another attendee. Until very recently, he was a sixth grade teacher at Neal Middle School in Durham.

“I was going to make sure I could bring back my experiences to my sixth grades classroom,” he said. “However once I accepted my new position, I was like ‘Oh I can expand this around the whole district now so I’m not just contained to one classroom.'”

But while the teachers learned a lot about eclipses in the morning, nothing could prepare them for the experience of actually witnessing the event that afternoon.

“It was fabulous. I mean, words are…uh, speechless really. It’s definitely something I’ll never forget. It’s already, I mean, you can see me right now. I’m lost for words. It’s an experience that can’t be replicated,” Campbell said.

“It was way cooler than expected,” Scott said. “I didn’t expect it to be so dramatic.”

Check out the reactions of the crowd during totality below.:

Brock Womble, executive director of NCCAT, said he decided to have the program after a conversation with Jackson County’s school district superintendent.

“As soon as he told me about it, it immediately sparked interest,” Womble said.

He also said that given how fortunate NCCAT was to be in the path of totality, it was something he could do to give back to the teaching community.

“It was really just an opportunity to take the location where we’re at…and be able to share it with the teachers of North Carolina,” he said.