My mother was a teacher’s assistant, so I had the whole place to myself in the afternoons.

Long after the buses left and the cafeteria was cleaned.

Long after the gym was locked and the office staff was gone.

It was just me.

Left to wander as my mother wrapped up her work, I would ramble aimlessly around the old school building.

What I remember most is the stillness of the place with no one there, the negative print of a typically bustling and harried school day.

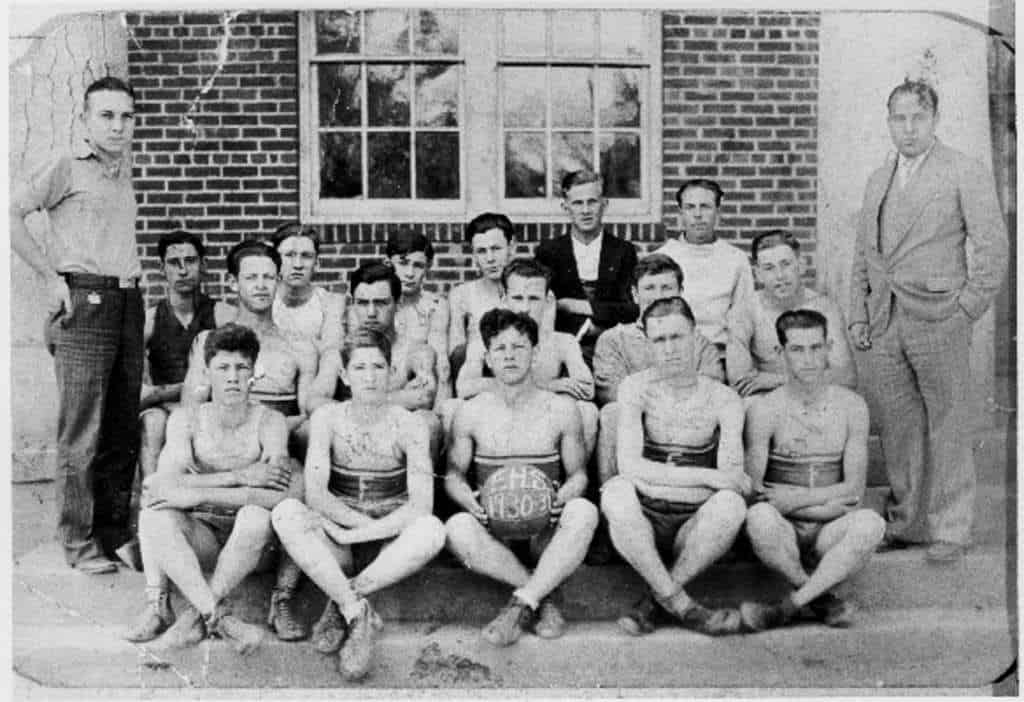

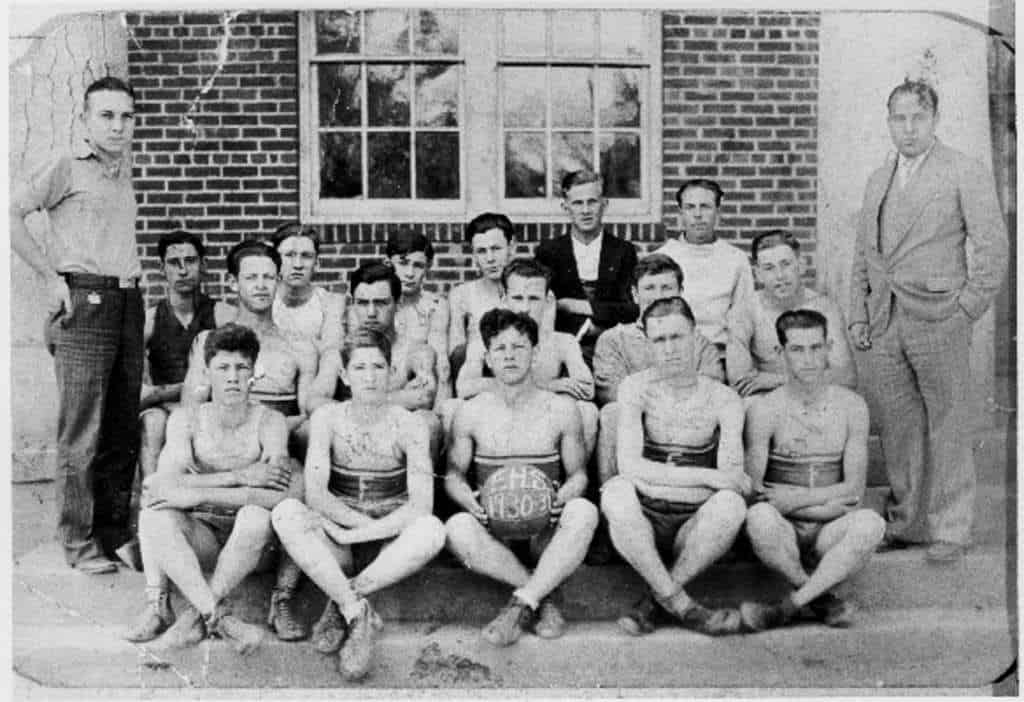

Randolph County Public Library – Randolph Room:

http://www.randolphlibrary.org/historicalphotos.html)

Built in the 1920s but standing as a school for almost a half century before that, Farmer School was the center of the small unincorporated community of Farmer in the southwest corner of Randolph County.

If you were lost in the county and stumbled upon that little unassuming place, it would have been a wholly unimpressive experience. It was nothing more than a general store, post office, school, church, and a green Grange Hall building, which by the time I arrived at Farmer in the late 1970s was beginning a slow dissent into irrelevance and disuse.

But the school was the heart of the place. It was a towering physical presence compared to the modest landscape. The two-story main building where my mother worked was the oldest structure. Expanding out to one side stood a collection of newer, more recent additions: another classroom building, a gym, cafeteria, maintenance building, athletic fields and water tower. It was like a physical timeline unfolding from old to new.

But it was the original school house that fascinated me as a child during those quiet afternoons when it was mine alone to explore. When I sat in the stillness of the light that poured in from the windows lining the building’s high monitor roof.

The floor pitched as you walked in the entrance and gave the visual and physical sensation of pulling you into the stage at the end of the auditorium — the heart and soul of the school that sat dead center under that elevated roof. Around the edges were the classrooms, set in relief, highlighted by an open hallway on three sides.

The layout inspired a certain reverence when someone left a classroom to go to the bathroom or the administrative offices at the front of the school. Reverence not out of respect but from necessity. The open, cavernous space at the center of the building carried any sound, however intentional or unintentional.

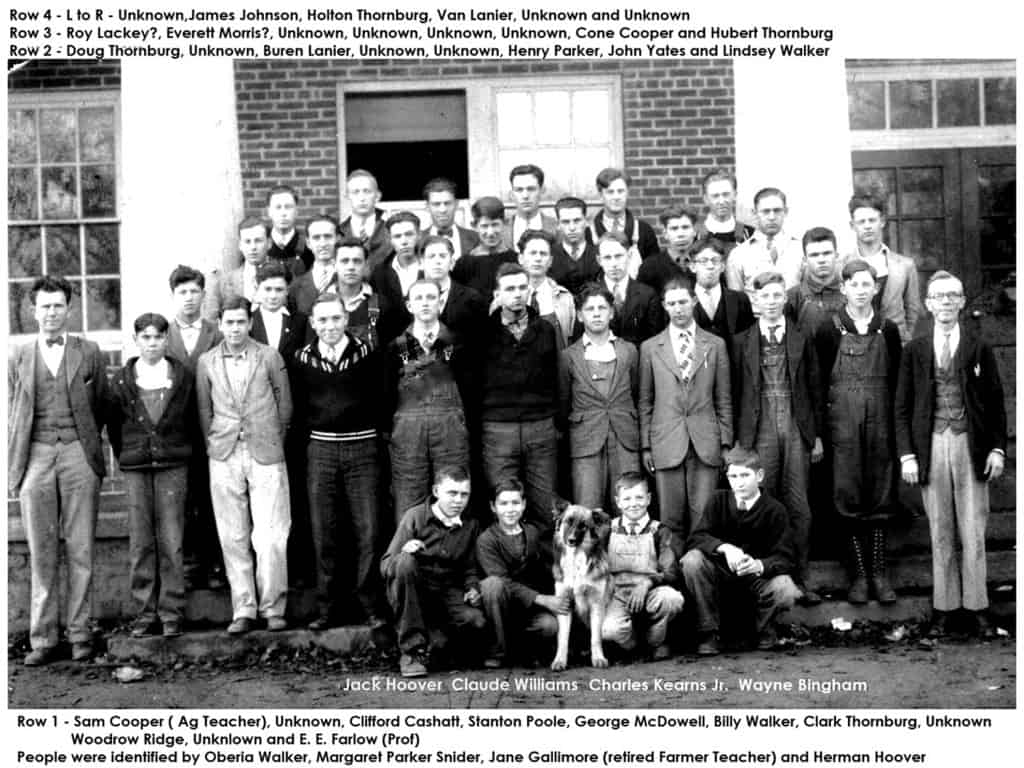

Randolph County Public Library – Randolph Room:

http://www.randolphlibrary.org/historicalphotos.html)

Some years after I left Farmer, a new school was built. It’s farther down the road, away from the old school grounds and the heart of the community. It sits closer now to the more accessible highway, easier I am sure for parents and school buses to navigate. Easier than navigating the twist and turns to the old one-lane Dunbar Bridge we had to cross every morning.

Do they understand what they have sacrificed to convenience? The experience of crossing that old bridge and seeing the slow, murky waters of the Uwharrie everyday.

After the new school was built, the old buildings were left empty and quickly fell into disrepair. The roof partially caved in on the old school building and a fire in the basement left a patch of charred brick on the side.

The post office, general store, and Grange Hall all closed. The structures are still there, but the life is gone.

Last winter, I heard the property had been purchased and was being renovated for a private academy. One weekend home, I decided to stop by and see for myself.

The new owners graciously gave me a tour of the place, showing me the renovations. The walls had been peeled back to the studs, and you could touch the old wood that was put into place almost a century ago.

My host told me that when they tore down the walls, they found the wooden bones of the building to be perfectly in plumb.

That seemed right to me.

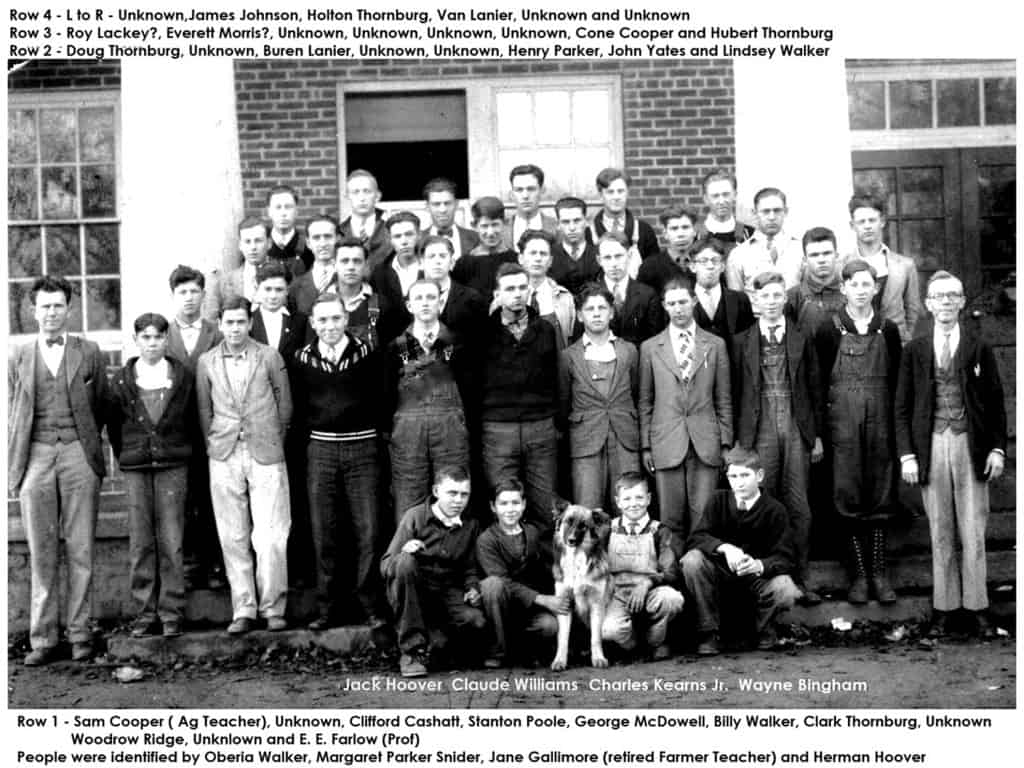

Randolph County Public Library – Randolph Room:

http://www.randolphlibrary.org/historicalphotos.html)

Not long ago, I was describing that building’s physical presence to a friend. After listening to me talk about the diffuse light that entered the scattering of windows from the top arch of the roof and the introspective nature of being alone in a large, still place, she paused and said, “It sounds like a pretty sacred space to you.”

It struck me as odd and wrong. It made me think that maybe I had mythologized the place too much in my young mind, sparking an internal narrative that had stuck with me into adulthood. That perhaps I had projected a feeling on the place that wasn’t based in any physical reality.

Maybe like all perceptions, it was a mental frame that said more about me than the building.

But the more I thought about it, the more I realized she was right. The place has always seemed sacred to me. Maybe it was because I had access to it and a vantage point others of the same age did not. Maybe I was just an unfocused daydreamer as a child and anything of that size would have captured my imagination.

Regardless, the sense has stuck with me throughout my adult life.

But as I grew older, I realized the school’s sacredness was inherent not in its structure but in the role it played in the community.

The very layout of the original school house was communal by design. A common gathering spot beckoned from the heart of the building. The auditorium greeted you first when you walked through the big double doors at the entrance, framed by the large plaster columns in the front.

It was the focal point not only of the physical building itself but the larger community that sat just outside its doors.

For years before me, students walked through those doors and sat in those hard, unforgiving wooden seats, parents watched class plays, kids and adolescents made speeches, minds wandered, and in the gym, young athletes won and lost basketball games against places with names like Tabernacle and Gray’s Chapel.

Who knows the happiness and sadness those wooden seats had seen? Who knows the stories they have to tell?

At EdNC we talk a lot about the importance of schools as physical spaces in our communities. But schools are also a connection to the past, to the lives of the young men and women who came before us, to the lives that defined the communities we were born into, which in turn defined who we are and will be.

In that way, they are a sacred space, a space that reminds us of the importance of community and the stories we share together, of our connection to the lives that came before us and the lives that will come after.

I wonder if that is what the architect was thinking when the plans for the old Farmer School were drawn. When he was working at his desk or looking out his window waiting for inspiration. Waiting for something to speak to him.

I choose to think it was.