“Can I take some home with me? I’ll keep really good care of them and feed them,”

promised Zamire as he turned his attention back down to the plastic blue bin.

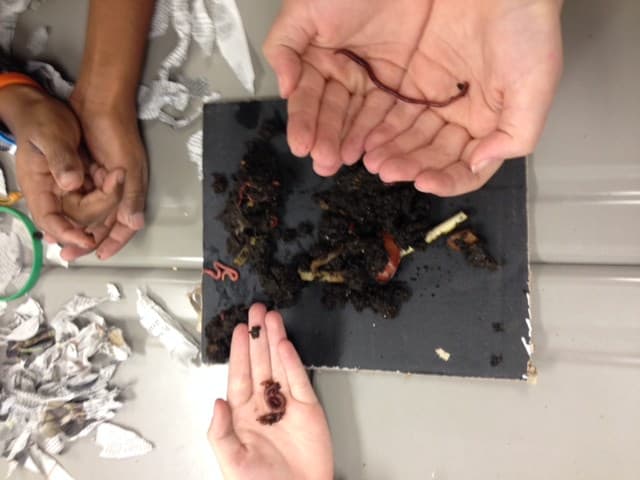

He reached inside and when his hands emerged they were gently cradling a mass of wriggling redworms. “They tickle!” He giggled as he brought his hands to his face to get a closer look. His fourth-grade science class was finishing a lesson on vermicomposting — using worms to compost and create rich soil. The previous weeks’ lessons had been about the importance of healthy soil for humans and plants to survive.

Just outside his classroom window, there’s a chicken coop, muscadine grape arbor, picnic tables, a weather station, and over 15 garden beds used to grow food. There’s a flat with over 50 collard and broccoli seedlings that will be planted later in the school day and during after-school classes. In a little over two months, the students will get to harvest the vegetables, and taste them in their classrooms.

The school district I serve with received a 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CCLC) Grant which helped fund garden programming at Aberdeen Elementary. The outdoor garden classroom itself was created by Good Food Sandhills in partnership with teachers and community members. The 21st CCLC program in my district works with a variety of community partners to provide additional academic programming to students attending low-performing schools who are enrolled in the local Boys and Girls Club.

As a FoodCorps service member, I serve during the school day in an elementary and middle school connecting kids to healthy foods through cooking and nutrition classes and partnering with teachers to reinforce curriculum standards through garden-based education, and collaborate with community members and organizations to implement programs to address academic disparities among students.

After school, I plug into the outdoor classroom and teach STEM classes. We use the garden as a tool to have students apply the math and science standards that they learn in the classroom to real life, hands-on projects. At the same time, they’re learning more about where their food comes from and getting excited in the process (because: worms).

Last year, students studied ecosystems, food chains, and weather patterns in the garden. The three school chickens — Tiger, Snowball, and Midnight — gardened alongside the students and prompted discussions about animal and plant life cycles. They also provided eggs, which the students learned how to (carefully) crack and scramble with spinach to create a healthy breakfast.

I worked with Zamire during this after-school program last year, too. And this year, I also teach him during the school day. I’ve seen that he thrives with the hands-on science activities. This week he helped plant more collard and broccoli plants. Using a square foot gardening template, the students laid bamboo sticks across the beds to create a 4’ x 4’ grid. They calculated how many squares we had total and placed one plant in each square. They added up how many plants they had planted as a group for a total of 48. After watering the newly planted seedlings (and their shoes), they gathered around the arbor to try muscadine grapes. On their way back to the Boys and Girls Club (located at their school), they shouted, “Thank you!” Their knees were dirty, faces sweating, but they all were grinning.

By teaching gardening, students learn interdisciplinary academic and personal skills. They are observing how their environment is shaped by relationships between plants and animals and the weather. Through growing food, they gain knowledge of where food comes from and the components of the food system, a connection that fewer and fewer adults can articulate.

In my experience over the last year, the garden is a great equalizer for all students. Students who struggle in traditional classroom settings can showcase their strengths in a garden classroom. Whether it is demonstrating to the class how to use a garden tool, identifying bugs, or strengthening teamwork skills, each student has an opportunity to feel like they have made an impact and is important to the success of the garden classroom.