I just checked the voter registration statistics for our state. There are 2,623,597 registered Democrats; 1,936,906 registered Republicans; 1,761,742 registered unaffiliated voters; and 26,774 registered Libertarians. As North Carolina finds its way as a purple state, it is important for us to consider policy perspectives from the far left to the far right and everybody in between. But it is just as important for us to consider the policy perspectives that different stakeholder groups have regardless of politics: students, parents, teachers, administrators, and the business community, for example.

As our state collectively considers policy changes, it is often really hard to thread together important issues that are related. It is easier to consider the issues in silos.

And too often education policy has too little to do with education practice on the ground in our classrooms.

Right now, our state is considering changes to the Common Core State Standards, changes to testing policy, and the opt-out movement is beginning to take hold.

Better state policies will be developed if we take the time to consider the different perspectives on each of these issues, how these issues play out in the classroom, and then work to address the issues collectively.

Common Core

Our Academic Standards Review Commission is working to review the Common Core State Standards.

I have empathy for the teachers who love and hate the standards, advocates on both sides who would like this resolved already, and the members of the Commission that are contributing their time to try to help us navigate this process as a state.

It is really important that the stakeholder groups walk away from this process believing that we have robust, appropriate standards that will ensure our students will succeed academically and professionally. Parents across the political spectrum need to feel good about them. Teachers across the political spectrum need to feel good about implementing them. Businesses needed to feel good about the quality of education we provide to students in North Carolina.

South Carolina has recently completed a similar process. It is not easy, but it can be done.

Testing

Testing raises the interest — and hackles — of stakeholders in ways we cannot afford to ignore as a state.

Remember Governor Pat McCrory’s 2015 State of the State Address? He said, “We will eliminate unneeded testing by next year.”

An EdNC intern, Liam Murray, is the author of an article about testing on our site that has the most pageviews to date — 8,138 — and the average time spent reading the article is seconds shy of five minutes. Even more astounding, almost 7,400 actions were taken with this article — you shared it on Facebook, tweeted it, emailed it, etc.

Administering the tests is frustrating for teachers. In an article, How should we measure teaching and learning in North Carolina?, Nancy Gardner tells us what it takes to administer a test at her school:

On Monday, it will be all hands on deck again to administer the tests, which will take the time of 81 certified staff members and 177 certified test administrators. In total, our school will require 247 student test accommodations, 2,627 tests, and 5,254 test booklets and answer sheets, the latter of which must be counted 3 times and then distributed.

We get it. You, North Carolina, you care about this issue.

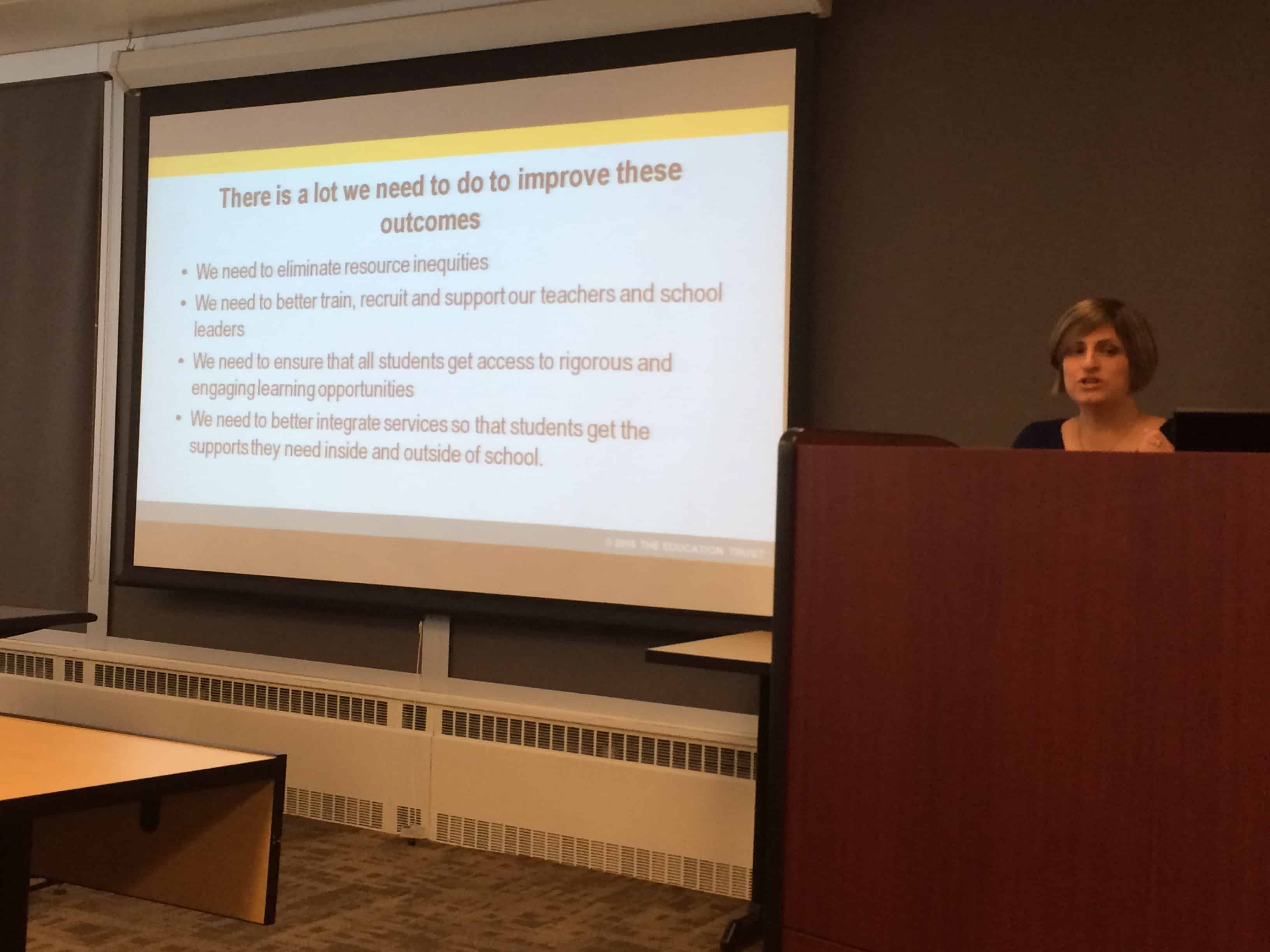

This week, I was on a panel on testing for the Governmental Research Association in Denver, CO. Natasha Ushomirsky of The Education Trust delivered this presentation on recent trends in school accountability.

Back in North Carolina, after months of work on a new testing strategy, The State Board of Education is moving forward with a testing study recommended by the Task Force on Summative Assessment. The general idea is to scrap our end-of-grade tests for grades 3-8 and replace them with 3-4 interim assessments, one of which would be conducted at the end of the year. In high school, there would be a pre-test in ninth and tenth grades and a post-test in grade eleven, serving as a college assessment.

In schools across the state this year, I have seen a wide variety of assessments. Here is an explanation of the difference between formative and summative assessments.

The state’s testing study will unfold as follows:

In 2015-16, the state will carry out a “proof of concept.” Between 3,500-4,500 students in grade five will be tested in math to determine the feasibility of the concept. Another 3,500-4,500 students in grade six will be tested in English Language Arts (ELA).

In 2016-17, a field test on a sample population of students will be administered. Grades 3-8 on math and grades 4-8 on ELA will test items for inclusion in tests.

In 2017-18, a pilot program will be implemented statewide.

Seeming to have learned from the implementation of Common Core, this study is being rolled out, tested in classrooms, phased in, and a communications plan will provide stakeholders with information from the get go.

Opt-Out

EducationNext released survey data earlier this week finding, “A clear majority of the public supports federally required annual testing and opposes those who would give families the right to ‘opt out’ of the requirement.”

In February 2015, the Education Commission of the States issued this report on the opt-out trend nationwide. On page six, you see can North Carolina’s opt-out policy.

In communities where opt-out takes hold, the risk to data collection is real. In Colorado, two rural schools districts have opt-out rates as high as 100 percent for some grades.

Mecklenburg Acts describes itself as a grassroots coalition of parents and citizens working to build community commitment to equity and excellence in all schools. On their website, they have an opt-out petition with 242 signatures to date. Given the state’s policy, the website explains the difference between opt-out and refusal.

As researchers, we need good data to evaluate education policies and think about how they need to be changed to make sure all of our students have access to a high-quality education. We need good data to know how our schools are doing. Teachers need assessments to understand where students are and provide remediation.

We need a testing strategy that as few parents as possible want to opt out of. Researchers need to figure out better ways to get the data out of the formative assessments that students, teachers, and parents seem to prefer.

In the meantime, teachers and parents, please weigh in on the state’s testing study. This is your chance to impact this change in public policy.

The Disconnect

Which brings me back to the disconnect between education policy and education practice.

At a forum I attended in Washington, DC earlier this year sponsored by the Hope Street Group, I was asked to read an article by Rod Paige entitled “Why has education policy produced such little improvement?” Paige was the Secretary of Education under George W. Bush.

In a pertinent part, Paige writes,

Education policy, which consists of the laws, rules, and regulations enacted to govern the operation of our system of education, is primarily formulated in state settings and tends to be heavily influenced by the work of education think tanks, education lobby agencies, education advocacy organizations, and the practical realities of political expediency. Those who actually teach the children, manage the schools, and do the work of school boards are minimally represented in this process. This unfortunate truth creates a dual negative.

First, education policy created in this manner cannot benefit from the perspective of those who know the educational environment best.

…

Secondly, and even more grievously, school professionals who are excluded from meaningful participation in the formation of education policy are likely to feel little ownership of the policy’s success. This leaves the policy void of meaningful practitioner advocacy.

The issues around Common Core, testing, and opt-out all stem in large part from this disconnect between those making the policies and those feeling the brunt of them. If we want changes in education policy to lead to student improvement, it is time to reconsider our process for threading these issues together in our public consciousness and how we work together to address the issues collectively.

As Paige notes, “teachers, principals, superintendents, and school board members are the major arbiters of school improvement….”

Our goal is clear: As Natasha Ushomirsky of The Education Trust said in Denver,

Constructing systems and policies that do the right things for kids.

Additional information

Common Core

Here are the ELA Common Core State Standards.

Here are the Math Common Core State Standards.

Here is Senate Bill 812, AN ACT TO EXERCISE NORTH CAROLINA’S CONSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY OVER ALL ACADEMIC STANDARDS; TO REPLACE COMMON CORE; AND TO ENSURE THAT STANDARDS ARE ROBUST AND APPROPRIATE AND ENABLE STUDENTS TO SUCCEED ACADEMICALLY AND PROFESSIONALLY.

Past meetings, agendas, and documents of the Academic Standards Review Commission.

Here are the members of the Academic Standards Review Commission.

Here are the upcoming meetings of the Academic Standards Review Commission.

Here are press releases from the Academic Standards Review Commission.

Testing

Report to the State Board on Testing Recommendations by the Task Force on Summative Assessment.

Testing Proof of Concept Study.