Contents

- African American Education Under The Peculiar Institution

- Black Education During the Civil War

- Postwar Progress: Presidential Reconstruction

- Radical Reconstruction: A New Dawn for Black Education?

- Rise of the Democrats and the Advent of Jim Crow

- Outside Influences: Rosenwald Schools and Philanthropic Societies

- A Watershed Decision and the Black Response

- Klan Violence and Desegregation

- The Civil Rights Act and the Fallout for Black Educators

- A Hyde County Affair

- The Swann Decision and Desegregation

- Resegregation and the Case of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools

- Today: The Promise of Freedom Hill

This is the companion report to “E(race)ing Inequities: The State of Racial Equity in North Carolina Public Schools” from the Center for Racial Equity in Education (CREED). Find all content related to “Deep Rooted” and “E(race)ing Inequities” here.

In the summer of 1865, newly liberated enslaved people from all corners of Edgecombe County gathered on a knoll just outside of Tarboro, North Carolina. There, Union officers informed them the Civil War had ended — their Day of Jubilee had finally come. They immediately decided to create their own settlement, separate from their former owners, just across the Tar River from Tarboro. Named after the hill where they’d learned of their emancipation, the community of Freedom Hill was born. Freedom Hill was later incorporated as the town of Princeville in 1885, named after a local carpenter.1 As the first town in the United States founded by freedpeople, Princeville epitomized both extreme socioeconomic inequality and unwavering perseverance in the face of systemic racism.

Freedom Hill was not, in fact, a hill, but a low, swampy area on the south bank of the Tar River — the only land available to its residents in 1865. As a result, Princeville has flooded at least seven times since 1800.2 Residents have rebuilt after each disaster because Princeville represented too much to abandon. Initially a refuge from intolerant and potentially hostile white society across the river, Princeville grew to symbolize a legacy of black autonomy in a state still struggling with the cultural and institutional legacy of slavery. Moreover, the efforts of Princeville’s founders act as a lens, revealing which aspects of freedom were most important, not just to residents, but to blacks throughout the South during early Reconstruction: land ownership, economic independence, religious freedom, control over their own lives and the lives of their families, and education.3

Other than land ownership, freedpeople in the South just after the Civil War considered education perhaps the most critical vehicle towards autonomy; both rights had been denied them for centuries.4 Indeed, the storyline of Princeville, with its elements of resilience, self-reliance, outside aid, segregation, racism, and white backlash, reflects the dynamics of racial inequity and education in the state. But to understand the yearning for education and the inequality that followed in North Carolina’s African American communities like Princeville, one must first examine the status of black education during the colonial and antebellum eras.

African American Education Under The Peculiar Institution

Slavery was present in North Carolina from its inception as a colony in 1663. John Locke wrote in his draft of the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina that “[e]very freeman of Carolina, shall have absolute authority over his negro slaves.”5 From the outset, the Lords Proprietors of the colony established a headright system granting “fifty acres of land for every slave over fourteen years old imported into the colony.”6 As land and opportunity for whites grew scarce in the more established regions of the Chesapeake and Charleston low country, white immigrants poured into the northern Carolina colony, bringing an increasing number of enslaved people and a firm devotion to the institution of slavery.7

North Carolina’s slave system was not as advanced as those of Virginia and South Carolina during the colonial era. Other than Wilmington, the colony lacked a deep-water port and was hugged by a rugged coastline known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic,” where many ships perished due to rough seas and ever shifting shoals. Furthermore, North Carolina made little progress during the colonial period in terms of internal improvements, which hindered the economy and the creation of a slave regime on par with the Chesapeake or the rice coasts of South Carolina and Georgia. The colonial slave population was mainly concentrated in the eastern part of the colony where a relatively small number of wealthy planters established plantations reliant on slave labor. White settlers in the backcountry of colonial North Carolina lacked the economic means to procure large numbers of enslaved persons. Nonetheless, slavery lay at the foundation of North Carolina society and was foundational to the colony’s economy.8 According to historians Marvin L. Michael Kay and Lorin Lee Cary,

“Although not the principal labor system in all regions of North Carolina in the generation before the American Revolution, slavery formed an important source of wealth, prestige, and power almost everywhere in the province.”9

Chattel slavery in North Carolina relied on violence, coercion, and negotiation — including whippings, threat of sale, sexual violence, and an ever-changing legal framework — to control enslaved communities. Yet, despite the extraordinary lengths slaveowners went to preserve this racial hierarchy, the enslaved resisted, in acts that can be seen in virtually every aspect of life. Subtle examples included feigning illness, breaking tools, playing dumb, or working slowly, while more extreme examples included arson, running away, and revolt. As with most slave societies, the struggle for control over enslaved Africans by their white owners was constant.10 In other words, anecdotal stories of benevolent slaveholders watching over fields of content slaves do not align with the experience of those enslaved.

One of the most threatening acts of resistance — and a serious threat to the social order — was the education of both enslaved and free black people. Literacy brought opportunities for slaves to forge passes and free papers, to access and spread abolitionist literature, and to read the Bible, which was thought to encourage visions of freedom. Educated slaves threatened the very ideology surrounding slavery.11 Says historian Heather Andrea Williams,

“Reading indicated to the world that this so-called property had a mind, and writing foretold the ability to construct an alternative narrative about bondage itself. Literacy among slaves would expose slavery, and masters knew it.”12

Slaveholders in colonial North Carolina also associated literacy with the potential for uprisings and unruliness by slaves. For example, in 1762 two Virginia men noted the prevailing sentiment among slaveholders was that “it might be dangerous & impolitick to enlarge the Understandings of the Negroes, as they would probably by this Means become more impatient of their slavery & at some future Day be more likely to rebel they urge farther from Experience […]. [T]he most sensible of our slaves are the most wicked & ungovernable.”13

Testimony from the enslaved themselves is also revealing. During the Great Depression the Works Progress Administration employed people to canvas the country to find and interview people who had been enslaved before the end of the Civil War. WPA interviews of formerly enslaved people in North Carolina show both the yearning for education and the backlash from slave owners. For instance, a formerly enslaved woman named Hannah Crasson said, “you better not be found trying to learn to read,” explaining that “our master was harder down on that than anything else.” Patsy Michner recalled a similar experience, saying,

“You better not be caught with no paper in your hand; if you was, you got the cowhide.”14

Despite the risk, many enslaved people secretly taught themselves. A North Carolina woman named Charity Bowery said, “I have seen the Negroes up in the country going away under large oaks, and in secret places, sitting in the woods with spelling books.”15 When Robert Harris, a free black man, joined the American Missionary Association (AMA) to teach freedpeople in Fayetteville, he said, “I have had no experience in teaching except privately teaching slaves in the South where I lived in my youth.”16 He claimed his brother had taught slaves in Fayetteville as well.

The rare opportunities for free blacks to receive an education in North Carolina existed most transparently in the apprentice system. “Had it not been for the apprentice system,” says historian John Hope Franklin, “it is safe to say that the educational achievement of the free Negroes would have been far below the level that was attained.”

From 1762 until 1838, master craftsmen were required to teach apprentices to read or write, regardless of race.17 Moreover, some religious organizations, such as the Quakers, promoted teaching enslaved people and free blacks, but not in significant numbers.18

During the 1830s, whites in North Carolina cracked down on slave literacy and free black education. In 1829, David Walker, a free black native of Wilmington living in Boston, published his pamphlet, Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. Filled with rhetoric calling for the enslaved to revolt against their owners, Walker’s Appeal spurred a wave of anti–black education legislation across the South. Education and the “contagion” of abolitionism were finally fused in the minds of white North Carolinians, spurring declarations like this one from the North Carolina General Assembly in 1830:

“…the teaching of slaves to read and write, has a tendency to excite dissatisfaction on their minds, and to produce insurrection and rebellion, to the manifest injury of the citizens of this state.”19

Under a law enacted at the time, “Any free person, who shall hereafter teach, any slave within this state to read or write, the use of figures excepted, or shall give or sell to such slave or slaves any books or pamphlets, shall be liable to indictment in any court of record in this State.”20 Neither could slaves teach each other to read or write. If convicted, white offenders would be fined $100 to $200 or prison time, while free blacks faced fines, prison time, or whipping. A slave convicted under this law could receive “thirty nine lashes on his or her bare back.”21

Around the same time, calls for white education in North Carolina grew louder. In 1832, Reverend Joseph Caldwell, the first president of the University of North Carolina, said, “To one this destitute of opportunity and education…heaven is out of sight and hell but a note in language.”22 Caldwell was speaking only about whites. According to historian Harry Watson, in order to ease class tension among whites, reformers pushed for universal white education in the South to rid the white poor of their “blackness,” or ignorance.23

White education in the state slowly began to improve. In 1825, the North Carolina legislature created a state literacy fund and later offered matching grants to passed taxes to support primary schools. Furthermore, North Carolina became the first state to offer publicly funded universal white education.24

According to the Census of the United States in 1850, in North Carolina there were 553,028 whites, 27,463 free persons of color, and 288,538 enslaved persons for a total population of 869,039.25 By 1850, there were 100,591 whites and 217 free blacks attending school in North Carolina. Twenty-five counties had at least one free black enrolled in school, with Wake County being the highest at 52 students. According to John Hope Franklin, there were 12,048 free black adults in North Carolina, of which 5,191 (43%) were literate. Obviously, free black in the state were learning to read and write regardless if they were officially enrolled in school or not.26 In the mid-1800s, North Carolina’s slavery-based social structure lay at the root of inequity in education in the state — but that social structure soon would begin to crumble as the nation hurtled toward civil war.

Black Education During the Civil War

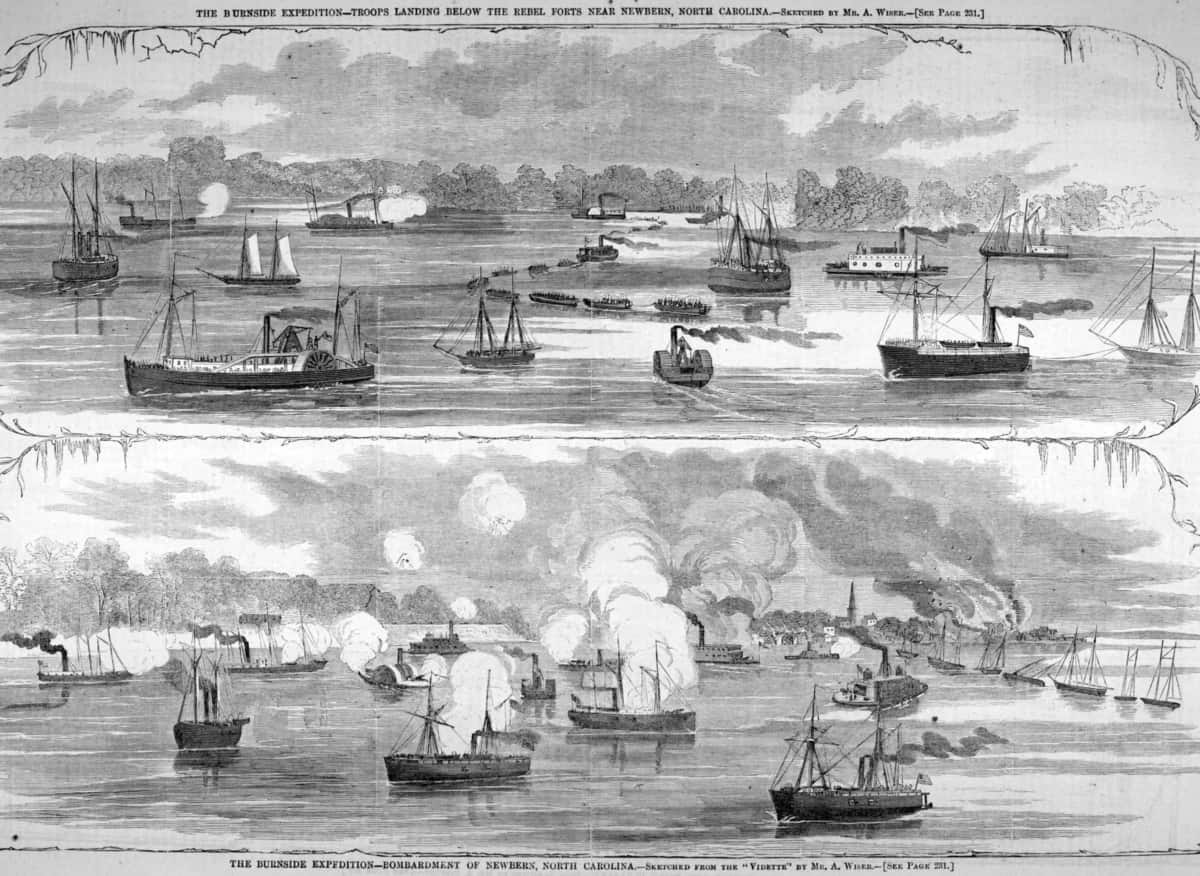

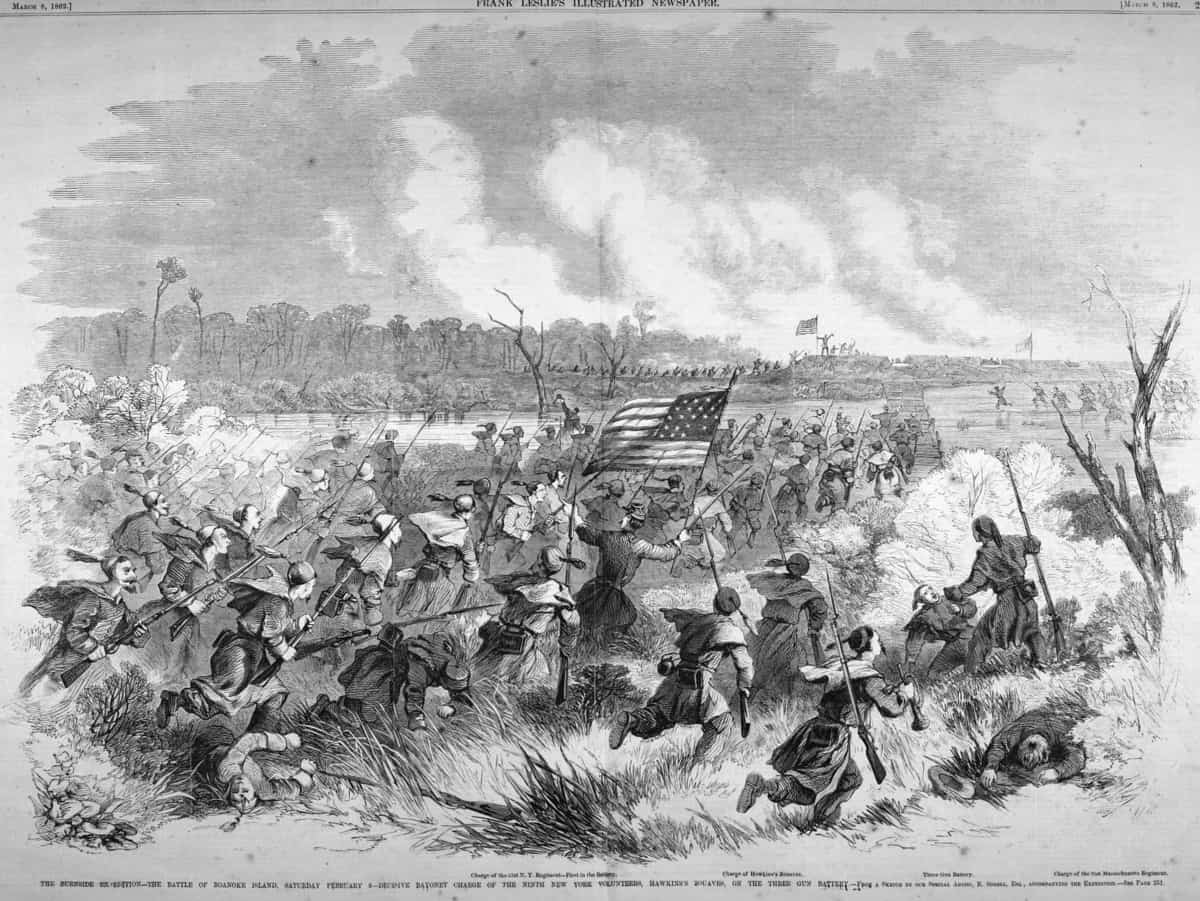

Much of eastern North Carolina fell under Union occupation early in the Civil War. Under the command of General Ambrose Burnside, Union forces captured New Bern on March 14, 1862, and sacked Beaufort 11 days later, giving the Union army a foothold in eastern North Carolina for the remainder of the war.27 Enslaved people across the eastern portion of the state flocked to Union-occupied territory for protection and to aid in the war effort for the North. One of the first aspects of free life for formerly enslaved people in Union-occupied North Carolina was access to education, which helped them distance themselves as much as possible from their former status.28 A Union soldier from Massachusetts alluded to enslaved people’s success in learning, saying, “[A]bout one in fifteen of the men, women, and children could read. We find many learned or began to learn before they were freed by our army — taking their instruction mostly ‘on the sly’ and indeed in the face of considerable danger.”29

Educated free blacks, Union soldiers, and northern aid societies in the region all contributed to African American education during the Civil War. Northern teachers almost immediately entered eastern North Carolina. Many of them had never seen a person of African descent before and were astounded at the efforts of freedpeople to further education and establish their own places of learning. Contrary to popular belief among whites at the time, African Americans were talented, eager students despite generations of enslavement.30 In September 1863, a teacher in New Bern with the AMA wrote that, to African Americans in the area, obtaining an education “seemed to be the height of their ambition.”31

In the months following the war, John W. Alford, the Freedmen’s Bureau’s national superintendent of schools, noted that

“[t]hroughout the entire South an effort is being made by the colored people to educate themselves. In the absence of other teaching they are determined to be self-taught; and everywhere some elementary textbook, or the fragment of one, may be seen in the hands of negros.”

Alford described a black-run school in Goldsboro, North Carolina, where “[t]wo colored young men, who but a little time before commenced to learn themselves, had gathered 150 pupils, all quite orderly and hard a study.”32

Makeshift schools occupied a variety of spaces. One teacher described a schoolhouse “…in a barn fitted up with seats for nearly four hundred persons.” The same teacher went on to describe very cold conditions during the winter months, but freedpeople still attended.33

When black men were permitted to enlist in the Union Army after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, they set up schools in the army barracks. Local black leader Abraham Galloway wrote to the Liberator, “The badge of slavery is superseded by the US uniform and the reading book and the slate are the accompaniments of these former victims of ignorance wherever they go. They hunger for the ‘forbidden fruit’ of knowledge with a zest of appetite which imparts marvelous powers of acquisition.”34

Yet the threat of local white backlash remained very real. In May 1862, military governor Edward Stanley ordered black schools in New Bern to close, citing state slave codes forbidding teaching blacks to read or write. The schools were closed, but later reopened.35 In 1864, three white men set fire to a black schoolhouse and threatened “the female teacher with violence unless she promised to ‘never again teach niggers to read.’”36 Despite such setbacks and racist attacks, the Union army’s presence largely allowed black communities in occupied eastern North Carolina to thrive. For example, By the end of March 1864, New Bern had 11 freedmen schools, while Beaufort had three. Nine more existed in other occupied parts of the state. In July 1864, there were about 3,000 African American students in school throughout the region — but the war’s end set the stage for enormous challenges.37

Postwar Progress: Presidential Reconstruction

In 1865 and the years that followed, freedpeople in the South began constructing their new lives and communities — like Freedom Hill, later Princeville — enabled by emancipation. One of the first things they did was to build schools. In many areas, freedpeople organized to pay for school buildings, supplies, and teachers.38 The Raleigh publication Journal of Freedom reported in October 1865,

“The Freedmen…has got a disease for learning. It is a mania within him.”39

The following year, delegates at the Freedmen’s Convention in Raleigh created a constitution for the Freedmen’s Educational Association of North Carolina to help improve African American education in the state.40 Observations from northern teachers in North Carolina under organizations such as the AMA and the Freedmen’s Bureau confirm this “mania.” Harriet Pike, a white woman teaching blacks in Wake County, observed, “Old and young are very eager to learn. Very often mothers in the midst of their children” learn from them what they had been taught that day. Moreover, Pike observed “men and boys who have to work in the cotton-fields from sunrise till dark, sitting under a tree studying a Primer during the few moments of rest they are allowed after dinner.”41

Along with the efforts of freedpeople themselves, the Freedmen’s Bureau and organizations such as the AMA provided crucial aid to black education in the South during the early months of Reconstruction. Education was one of the main avenues taken by the Bureau to reform southern society, and they had much to work with already. Schoolhouses built by freedpeople dotted North Carolina; those, along with financial aid and teachers provided by the AMA, were corralled by the Freedmen’s Bureau to create a “loosely organized, if still vulnerable educational ‘network.’”42

During the period of Reconstruction, North Carolina was embroiled in fierce political conflict between white Democrats, determined to hold onto the pre-Civil War racial hierarchy, and the bi-racial Republican party championing racial progress. Using violence to maintain control, white Democrats often resorted to violence and intimidation directed towards freedpeople. This racially motivated political violence was so endemic throughout the South that the Republican-controlled Congress passed the Enforcement Acts in 1870-71 to try and persecute white terrorist organizations.43

Whites burned down four schoolhouses in early 1866 and two more the following year.44 Also in 1866, two black men in Duplin County were forced to close their school after whites threatened to burn it to the ground. During the same time period, a northern teacher named Thomas Barton was dragged for miles by a white mob who called him a “G-d d—d Yankee Nigger school teacher” and said, “The Niggers were bad enough before you came, but since you have been teaching them, they know too much and are a damn sight worse.”45

Other whites, mostly elites, tolerated black education to an extent, believing “instruction for blacks should be aimed at creating a peaceful, hard-working black population which knew its proper place in southern society.”46 Upper-class whites realized a menially educated black workforce could be good for business, but felt overeducation of freedpeople might spur destruction of the southern racial hierarchy. Northern teachers were a main target of this fear. Said the Raleigh Sentinel, northern teachers were dangerous “because of their almost universal disposition to mingle, upon terms of social equality, with the blacks” and their teaching blacks ideals “intensely hostile to the peace and harmony of the races.”47

The General Assembly abolished the universal school system created for whites before the war. The majority of the General Assembly stated the decision was simply a fiscal necessity, but Union County state senator D.A. Covington pointed to another reason: white North Carolinians feared “[t]he Freedmen’s Bureau might force colored children into [the schools],” he said, “to which our people would never consent.”48 Still, the efforts of freedpeople and various agencies increased the number of schools for African Americans from 100 in December 1865 to 156 in March 1867. Likewise, the number of teachers rose from 132 to 173, while the number of pupils rose from about 8,500 to 13,039.49 Progress would continue, thanks largely to the efforts of freedpeople — but violence from native whites lay on the horizon.

Radical Reconstruction: A New Dawn for Black Education?

Congress passed the Military Reconstruction Act in 1867, ushering in a new era of Reconstruction in the South. North Carolina was required to draft a new constitution and adopt the Fourteenth Amendment, giving black men the right to vote. The progressive Republican party seized political control of the state in 1867, the year before a new constitutional convention would be held.

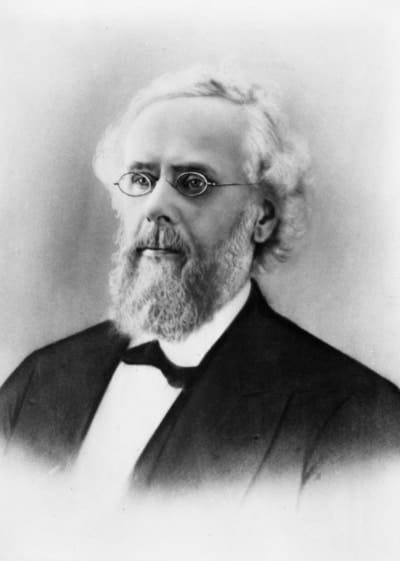

The Freedmen’s Bureau superintendent of education, F.A. Fisk, was sure that education would one day extend access to the ballot for black men, eventually allowing them to exert political and economic power to become first-class citizens.50 For a brief historic moment, Fisk’s prediction appeared to be a possibility. The state constitutional convention of 1868 proved to be a revolutionary moment for public education in North Carolina, officially adopting black education and creating a new universal public school system for blacks and whites to operate at least four months out of the year. A state superintendent would preside over the school system, while a state tax for schools would fund it.51 The first superintendent was Massachusetts native Reverend Samuel Stanford Ashley, who came to North Carolina with the AMA in 1865 and remained an ardent supporter of the education of freedpeople until his departure in 1871.52 While many white North Carolinians accepted black education to some degree, whites generally feared the intentions of northern teachers and wanted to control the curriculum in order to, as a Fayetteville newspaper put it, “develop in him a useful and profitable laborer.”53

The 1868 convention bypassed whites’ perceived threat of integrated schools using vague language. A resolution for segregated schools passed but failed to make it into the final draft.54 White backlash soon broke out across North Carolina. The Wilmington Daily Journal proclaimed: “Think of it, you men of families. You may die soon. … After you are gone, your children may be forced to go to school…with negroes.”55 Equal education threatened social order; whites and blacks alike knew the connection between education and the right to vote and participate in civil life. Thus, giving suffrage to black men and education to black children was bad enough, but the conservative Wilmington Daily Journal concluded that in the new state constitution African Americans could not be “excluded from occupying any place in a public church, public school, public hotel, or assemblage; he or she may claim, under the vital principle of the Constitution, the right to intermarry with a white person…”56

To conservative whites, black education led down a slippery slope — one they would not go down without a fight.

By 1869, as the Ku Klux Klan infiltrated North Carolina, racial violence targeting black education exploded. White teachers were beaten and threatened. Freedpeople grew warier of sending their children to school, especially at night. That year, Alamance and Orange counties alone saw 55 whippings, three hangings, one drowning, one shooting, three houses shot into, and two houses torn down. Later, a congressional investigation committee found 260 Klan visitations had occurred in 20 North Carolina counties by mid-1870.57 In this violent context, the state lost 49 schools, 511 teachers, and 1,683 students from the peak of the 1868–69 school term to the peak of the following year.58

Rise of the Democrats and the Advent of Jim Crow

In 1870, the conservative Democrats gained control of the North Carolina legislature and forced Superintendent Ashley out. His replacement, Alexander McIver, did not believe in integrated schools, nor did he seem to care about African American education in general. Democrats immediately adopted an amendment mandating segregated schools and enacted legislation that transferred public school funding from a state tax to a county tax, crushing the previous Republican system.59 The efforts of white supremacy within the Democratic party were gaining steam.

School segregation was a topic of heated debate during the Constitutional Convention of 1875. White Republicans abandoned African American legislators in the state General Assembly, leaving them no choice but to acquiesce in order to preserve the rights they had.60 White Republicans pushed instead for “mutuality,” essentially arguing that African Americans should have control over their communities separate from whites. Mutuality later morphed into a Democratic argument for segregation. Voters ratified the new state constitution in 1876, legally mandating segregated schools.61

In the early to mid-1880s, the education system in North Carolina remained ineffective for both African Americans and poor whites. Nearly half the state’s population was illiterate. Racial and class conflict bred a general animosity towards education, especially publicly funded education. Whites, in particular, did not want their taxes to help fund black education, feeling, as the Greenville Eastern Reflector wrote in 1887, that educating blacks “ruined a field hand.”62 Sharecropping had, in effect, replaced slavery and guaranteed a reliable black labor force, but education could threaten everything.

In 1881, the federal government began offering aid to states that met certain requirements under the Blair Bill, which “called for a direct appropriation from the national treasury, to be distributed to the states based on illiteracy.”63 The Republican-controlled state senate championed a series of Blair’s bills over the next decade, but the Democrat-controlled house blocked their efforts every time. While Democrats did support the idea of federal aid for education, they did not believe the federal government should place requirements on that aid, especially tax increases.64

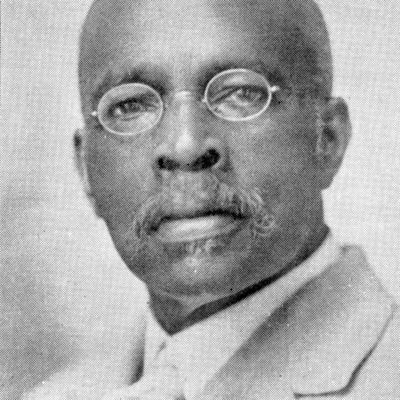

The most ardent supporters of federal aid for education were African American legislators and educators. For example, James E. O’Hara, an African American state legislator, introduced companion legislation to the Blair Bill in 1886 that died in committee. African American educator and editor Charles N. Hunter convinced Blair himself to speak on the subject of education at the Negro Fair in Raleigh on November 11, 1886. In his speech Blair proclaimed that freedmen needed “land and education” and that “the first quality of a freeman is knowledge, for knowledge is power.”65

Political debates over federal aid raged throughout the 1880s; meanwhile, the state system of educational funding through taxes became highly unequal. In 1881, the General Assembly passed a bill providing property taxes from white landowners to fund white schools and from black landowners to fund black schools. Because whites made up the vast majority of landowners in North Carolina, this bill was a boon to white schools. For example, in 1886 in New Bern, per-pupil spending at the local public schools was $11 per white student, but $5 per black student.66 Said the Democratic Raleigh News and Observer: “Each race should be responsible for the education of its children.”67

Though segregation and Jim Crow continued to strengthen in the state, in 1886 the state Supreme Court found the 1881 tax law unconstitutional, citing the discrepancy in public education funding based upon race.68 White backlash over this decision reverberated throughout the state, as shown when a local paper in New Bern said,

“A constitution that will not allow the white people to tax themselves for the benefit of their schools, after they have contributed liberally to negro schools, is not the constitution that the white people of North Carolina want.”69

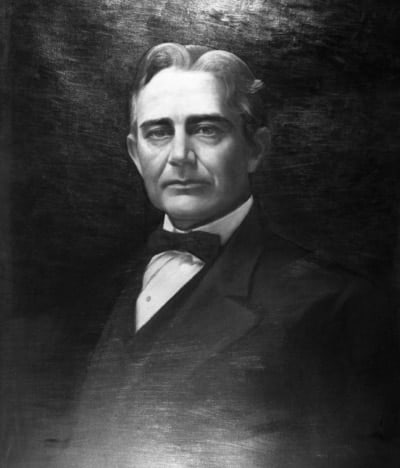

During the gubernatorial campaign of 1900, Charles B. Aycock tapped into the racism of white North Carolinians and used it to his political advantage. Aycock, a Democrat who had been lauded as the state’s “education governor,” ran on a platform of black voter disenfranchisement and universal education. After his electoral triumph in 1900, Aycock and the Democrats soon etched obstacles to voting into the state constitution.

Indeed, Aycock was no progressive southerner when it came to education; his intentions were directly connected to suffrage and white supremacy. According to North Carolina’s grandfather clause, all white males whose ancestors could vote in 1867 would be allowed to vote, whether they were literate or not. Most African Americans could not satisfy such criteria, since free blacks were banned from voting in North Carolina in 1835, while newly freedpeople did not gain the right to vote until 1868. Moreover, any white man who could read and write by 1908 would be able to vote thereafter, yet black men faced more difficult challenges to voting, such as the threat of white violence, even if they were literate. Thus, Aycock began advocating education for poor whites in order to ease illiterate whites’ fears of disenfranchisement.70

The Aycock administration also changed the tax code as it related to education funding, placing a higher tax burden on African Americans while disproportionately allocating funds towards white schools. James Y. Joyner, a staunch ally of Aycock and the North Carolina superintendent of public instruction from 1902 to 1919, traveled the state advising local districts on how to allocate education funds to favor whites. In one letter to a local superintendent, Joyner wrote: “In most places it does not take more than one fourth as much to run the negro schools as it does to run the white schools for about the same number of children. The salaries paid to teachers are very probably much smaller…if quietly managed, the negroes will give no trouble about it.”71

The gap between black and white public education in North Carolina increased dramatically. From 1904 to 1920, annual spending per white school averaged $3,442 but only averaged $500 for black schools. School terms were longer in white majority counties that levied local taxes than in black majority counties. For example, in 1914 the average term for locally taxed white counties was 137 days, compared to 120 days in black counties.72 Funds for rural black schools in North Carolina often went instead to rural white schools: Charles More, field organizer and inspector of rural schools in North Carolina at the time, wrote the State Department of Education that,

“thousands of dollars earmarked for black education had actually been spent to build schools, hire additional teachers, or increase the school term for whites.”73

Funding discrepancies created daunting obstacles for African American teachers and students. Most African American teachers were women because their lack of education, plus the opportunity to make more money in industrial and agricultural labor, steered many African American men away from the profession. Even educated black women had few professional options, so many became educators, despite significant challenges. Historian Valinda Littlefield found that African American teachers in North Carolina were paid an average of $20 less per month than white teachers, regardless of education or experience. Black teachers faced much larger classroom sizes and were given highly inadequate resources compared to white teachers.74 According to one contemporaneous African American teacher in North Carolina, named Lola Solice,

“[T]he only supplies black teachers received from the county were a broom and a bucket [….] [T]extbooks for the black schools were rented by African American parents, and they were always second hand books from the white schools.”75

Conditions were so poor that white northern philanthropists, pitched by Booker T. Washington and other black southern education leaders, began to send aid to southern black schools.

Outside Influences: Rosenwald Schools and Philanthropic Societies

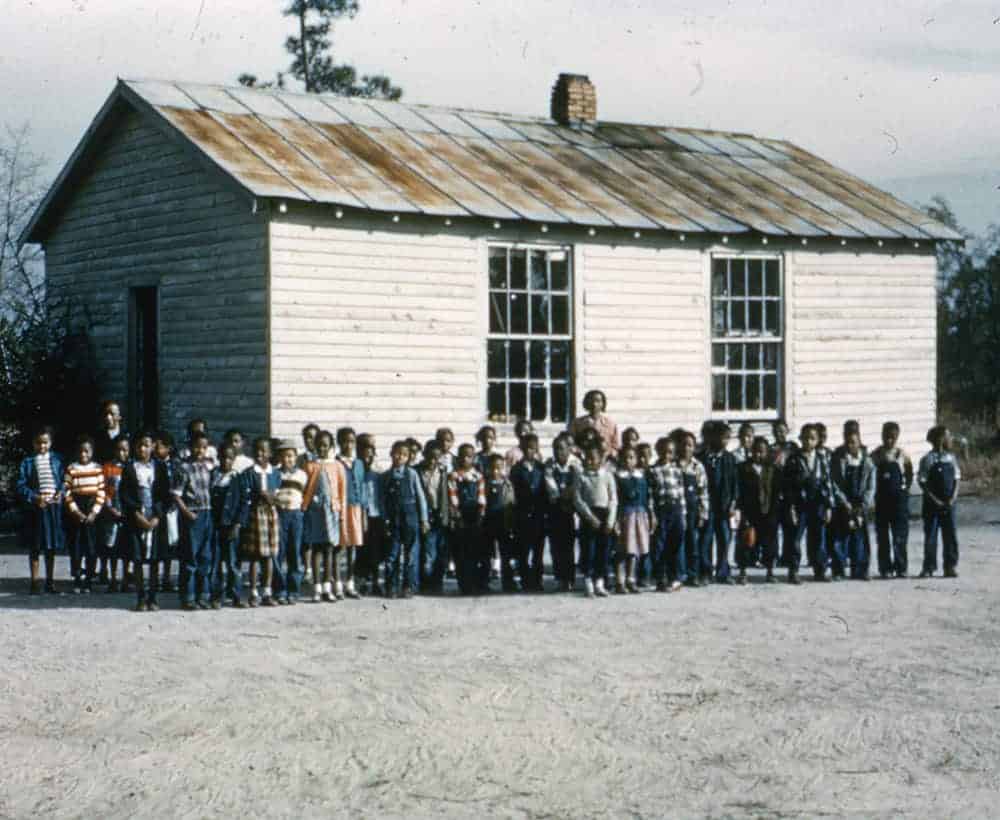

Northern white philanthropic efforts towards southern blacks date to the Civil War and the American Missionary Association. Such groups dwindled after Reconstruction. But the legacy of northern philanthropy was revived in 1910 when Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck, & Company, acceded to pressure from Washington and provided matching grants to rural southern communities that agreed to build black schools. Officially created in 1917, the Rosenwald fund dramatically improved North Carolina’s black educational facilities.76

The Rosenwald fund not only supported the construction of hundreds of black schools but also demonstrated black North Carolinians’ dedication to education. By 1932, when the fund dissolved, more than 800 Rosenwald buildings stood in North Carolina, more than in any other state.77 Many of the female African American teachers who taught in Rosenwald buildings were trained and paid by another northern philanthropic society, the Anna T. Jeanes Fund. In addition to teaching, Jeanes’ teachers, “went into the community to instruct residents in modern healthcare, child rearing, and home economics.”78 These efforts did not go unnoticed, as Nathan Carter Newbold, the North Carolina Director of Negro Education (created in 1921) later remembered:

“School Superintendents, Jeanes teachers, General Education Board Agents, County Training School Principals, and people, all seized upon the Rosenwald school as something visible, tangible, an evidence of progress in Negro education that could not be gainsaid. It probably was the ‘missing link’ all agencies needed to round out a complete program for Negro schools.”79

Difficulties remained: for instance, one student who attended a Rosenwald school in Mecklenburg County in the 1930s recalled, “When you got here [in winter], it was terrible. You’d be so cold your fingers, they’d just ache like a toothache.”80 Nevertheless, the Rosenwald fund injected much-needed support into black education in North Carolina.

The state’s investment in black schools increased from $1.28 million during the 1919–1920 school year to $4.53 million by the 1927–1928 school year. Investment in white schools grew even faster, exacerbating funding discrepancies. During the same period, the value of white schools rose from $10.69 million to $50.05 million. Disparities in per-pupil spending increased as well. For example, during the 1914–1915 school year, the state spent $2.77 per white student, which rose to $3.11 per white student in 1932. During the same period, spending per black student remained steady, at just $1.00.81

African American communities used white disregard for black education as an opportunity for community cohesion and autonomy. According to historian Barry F. Malone, “As blacks labored to invest time, materials, and money, the community developed a real sense of ownership and governance.” Yet, Malone says, “Surrender of this control became problematic for both races later during the integration process.”82

A Watershed Decision and the Black Response

As the nation emerged from the Great Depression and World War II, the issues of race and educational equality again came to the forefront. Indeed, the spring of 1954 was a social and legal watershed moment in United States history. Since the Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896, which paved the way for Jim Crow and segregation, the “separate but equal” doctrine had ruled the South.83 But in May 1954, the United States Supreme Court overturned the Plessy decision in Brown v. Board of Education,84 stating that, in terms of public education, schools separated by race were inherently unequal and violated black children’s Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection under the law.85 But the road to end segregation was far from over. Prophetically, on the day after the Brown decision, the mayor of Tarboro proclaimed, “It will be a long time before any such change takes place,” adding, “None of our present traditions of segregation will be interrupted unless and until we are advised that they are improper.”86 White resistance would continue to stall integration in North Carolina and throughout the South.

Whites’ initial reactions were calculated and restrained. Governor Umstead said, “[the Supreme Court] has reversed itself and declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. In my opinion its previous decision on this question was correct. … Overnight, this decision has brought to our state a complex problem … the wise solution of which will require a calm, careful, thoughtful study of all of us. There is no time for rash statements or the proposal of impossible schemes.”87 Like many white North Carolinians, Umstead hoped the process of integration could be slowed as long as possible.

Before his death in November 1954, Umstead created a Committee of Education consisting of 19 members, only three of whom were black. Committee chair Thomas J. Pearsall was bombarded with letters from alarmed white North Carolinians.88 One typical letter stated,

“Expensive as a bi-racial system of education is to maintain, we had rather bear the burdens of heavier taxes than to obtain the status of a gigantic southern Harlem where the races are often indistinguishable.”89

Committee members agreed desegregation was not their goal, and their proposals to the legislature confirmed so. For instance, the Pearsall committee proposed a plan that shifted student-assignment authority from the state board to local districts, effectively giving local districts exclusive power to maintain segregated schools. The plan also allocated public money for school relocation (a system very similar to North Carolina’s current voucher program).90 In 1955, Luther Hodges, Umstead’s successor, appointed a second committee, again headed by Pearsall, with just seven members, none of whom were black. Moreover, in May 1955, the Supreme Court issued its Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka II decision, upholding that segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment. However, the court declared no timeline for integration, only saying states should do so “with all deliberate speed.”91

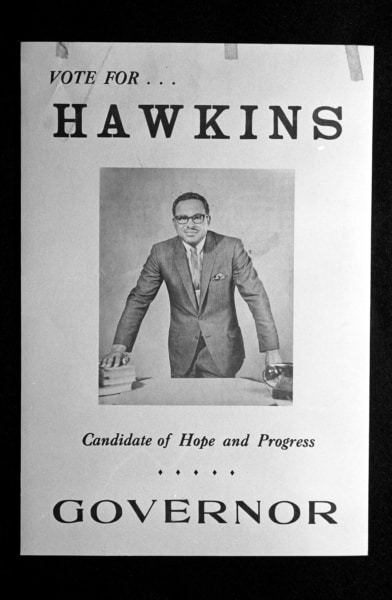

Such vague language gave North Carolina segregationists the green light to stall integration. In early 1956, Governor Hodges unveiled the second Pearsall plan to the state legislature. This follow-on supported the continuation of the student-assignment plan and proposed a constitutional amendment that would allow local communities to close local schools if ordered to integrate by the federal government. That November, the public voted to adopt the amendment by a margin of 471,657 to 107,757.92 By 1957, only three school districts in North Carolina — Charlotte, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem — agreed to send a small number of black students to all-white schools. Sending white children to black schools was out of the question. These were the first instances of voluntary desegregation in the former Confederate states.93 And although the state preserved its reputation for racial progressivism (largely because no schools closed in response to desegregation as opposed to states like Virginia), when black student Dorothy Counts walked towards the all-white Harding High School, she was met with “stones, spit, and racial slurs.”94 Local civil rights activist Reginald Hawkins escorted Counts out of school at day’s end out of fear for her safety, where they were once again subject to “a shower of spittle, pebbles [and] sticks. They tore our clothes [and] the police just stood there and did nothing.”95

Many white North Carolinians felt threatened by Brown and supported the slow pace of integration enabled by the Pearsall legislation. The black community had mixed responses. Throughout North Carolina history, in the face of legal, economic, and social obstacles, African Americans had built proud communities that they controlled and took pride in, schools included. And while some blacks rejoiced in the wake of the Brown decision, others were concerned. In late 1954, black residents of Maiden petitioned the Catawba County school board, stating,

“We want to keep our school and we want equal facilities, but we don’t want integration.”96

African American organizations like the North Carolina Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers and the NAACP called for integration in varying degrees, but none advocated more than Charlotte civil rights leader Reginald Hawkins. The events at Harding High, Hawkins concluded, could be used to publicly shame segregationists while pushing a more radical integrationist agenda. “The only way to move forward,” he said, “is to engage bigots in direct controversy within their own community.”97

Convinced that the Charlotte NAACP was taking too moderate a stance on integration in order to please the city’s powerful white business and political leaders, Hawkins took matters into his own hands, resigned as the chapter’s secretary, and formed the Mecklenburg Organization for Political Affairs (MOPA) in 1958. According to historian Michael B. Richardson, Hawkins thought the local NAACP had failed to mobilize Charlotte’s black community as a political force. “Hawkins argued that the political power — the ability to engage previously apolitical people, to rally the politically inclined, and to leverage votes into concrete gains — was largely an untapped force in Charlotte that MOPA intended to utilize,” Richardson says.98

By 1960, only three black Charlotte students had been admitted into white schools. In 1961, the only school boards to admit a handful of black students to white schools were Chapel Hill, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Durham, Greensboro, High Point, Raleigh, Winston-Salem, Wayne, Craven, Ashville, and Yancey. Both white and black leaders pushed for equalization of facilities rather than integration, which further hindered the process. Even though white officials put more money into black schools — resulting in the improvement of black education — the disparity in funding between white and black schools remained.99

Despite this slow progress, Hawkins remained a fiery voice for integration. He led a boycott in 1961 when the Charlotte school board proposed to build a new high school for white students and send black students to the old white high school, Harding, where Dorothy Counts had faced an angry white mob a few years earlier. Hawkins proclaimed, “We can’t send our children to school when they’re sick…So on Tuesday morning let’s everybody be sick — sick of segregation and hand-me-down-it-is.”100 Even as Hawkins’ strategy of mass resistance increased pressure on the school board, he would play another part in a revolutionary court case regarding integration in public schools.

Klan Violence and Desegregation

As the Civil Rights Movement gained steam, and as African Americans continued to push for integration, white backlash and resistance took extralegal forms. All around the state, black students who tried to enter white schools were physically and verbally assaulted. State and local governments were forced to increase the police presence at several schools.101

Ku Klux Klan membership spiked as token integration attempts continued during the late 1950s and 1960s. Crosses were burned in front of several schools in Greensboro and in the yard of Superintendent Ben L. Smith. In October 1957, a bomb detonated in front of the home of a black family whose children attended an all-white school in Greensboro. After an investigation, police told Governor Hodges the culprit was “the negro element of the NAACP.”102 During the same month, the Klan held a rally in Robeson County and tried to hold another a few months later, in January 1958, but were thwarted by a group of Lumbee, the local Native American tribe. Embarrassed by that defeat, the North Carolina Klan vowed to take its violent resistance underground. Rumors spread in Greensboro and Charlotte that the Klan had amassed arsenals of automatic weapons and would use them if necessary. Tensions were rising.103

By 1958, there was ample evidence the Klan intended to make good on their threats. In February, Charlotte police stopped a car of white men loaded with dynamite after a tip came in that the Klan was planning to bomb the Woodland Negro School. Klaverns were uncovered throughout the state, and public Klan rallies took place throughout 1958, including a public rally of 75 to 100 Klan members in Greensboro in June. At a July rally, one speaker threatened,

“If the Pearsall Plan doesn’t work, the Smith and Wesson Plan will.”104

Despite the very real threat of violence, isolated attempts at desegregation continued to occur throughout the state. The Chapel Hill–Carrboro school system became the first in the state to implement a voluntary and system-wide desegregation plan during the 1962–63 school year. Other school districts cautiously became more serious about desegregation plans.105

By 1963, the Civil Rights Movement was reaching a climax in North Carolina. Thousands of demonstrators in cities such as Raleigh and Greensboro marched, demanding the integration of public spaces and accommodations — and that the federal and state governments finally grant African Americans all of the rights of first-class citizenship. This massive display of resistance and civil disobedience sparked yet another spike in Klan membership and activity. More than 2,000 Klansmen gathered outside Salisbury in August 1964 to hear Grand Wizard Robert Jones rail against Governor Terry Sanford. Klan members bombed a black church in Craven County and a black elementary school in Smithfield in 1965. That same year, the homes of civil rights leaders Frederick and Kelly Alexander, Julius Chambers, and Reginald Hawkins were bombed. Thankfully, no one was hurt, but the cases went unsolved.106

The Civil Rights Act and the Fallout for Black Educators

Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law on July 2, 1964. Now the U.S. Attorney General had the power to bring lawsuits on behalf of African American plaintiffs in local school districts still practicing segregation. This tool proved critical in North Carolina, where local school districts had been given considerable power under the Pupil Assignment Act nearly a decade earlier. The 1964 act also granted the U.S. Secretary of Education power to collect data from local school boards to monitor the progress of desegregation — evidence that could be used in legal challenges to local school districts accused of postponing Brown.107

The Supreme Court strengthened the Civil Rights Act in 1968 through Green v. County School Board of New Kent County in Virginia.108 This decision provided lower courts the legal direction to desegregate after ending its policy of “all deliberate speed” in the 1964 Civil Rights Act. While most public school districts desegregated their schools between 1968 and 1976, white parents left public schools for all-white suburbs or private schools – a process now known as white flight.109

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Green decision in 1968 finally gave the federal and local governments the legal teeth to implement desegregation. Most of the black community applauded these developments, but not all of the impacts positively affected them. Says historian David Cecelski,

“Black communities repeatedly had to sacrifice their leadership traditions, school cultures, and educational heritage for the other benefits of desegregation.”110

Black educators bore perhaps the most negative outcomes of desegregation. There were 620 black elementary school principals in 1963 in North Carolina; by 1970, that number had plummeted to 170. By the end of the 1970s, there were no black superintendents in any of the state’s 145 school districts, and 60% of those districts employed no black administrators, even though black students made up 30% of the student body. Black teachers, to a lesser but significant degree, suffered as well, becoming expendable as black and white schools merged. By 1972, more than 3,000 black teachers in North Carolina had lost their jobs to their white counterparts. Only in Texas did a higher number of black teachers lose their jobs. More and more black students sat in classrooms led by teachers who did not look like them, could not share their experience of being black in a white-dominated world, and often did not have their best interests in mind. Countless black students suffered academically as a result.111

A Hyde County Affair

The most extreme case of African American resistance to desegregation occurred around this time in Hyde County. In the summer of 1968, the local school board, in cooperation with the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, the Office of Civil Rights, and the Department of Health, Education, and Wellness (HEW), approved a desegregation plan for the county. As was often the case in North Carolina, black students would attend previously all-white schools, and the black high school, O. A. Peay, would become an administrative building. Alarmed and enraged, blacks in Hyde Country organized and petitioned the school board to craft a new plan that would keep the black schools open.112 The board refused, prompting black residents to take dramatic action. Abell Fulford Jr. recalled,

“We decided that they couldn’t implement their plan without students, so that we would boycott the schools until they listened to us, until they agreed to keep the schools open. … We wanted integration but we would have taken anything so long as we still had our schools.”113

By September, black citizens of Hyde County had taken to the streets in protest and made good on their threat to boycott the school system — very few black parents sent their children to the white schools at the start of the 1968–69 academic year. As the boycott went on, racial tensions continued to rise. After four weeks, Hyde County’s black parents, concerned about the amount of instructional time their children were missing, developed a short-term plan to re-open the black schools and maintain segregation until they could pressure the school board to develop a desegregation plan that would save their schools for the long term. (One-way desegregation was not a long-term option.) However, HEW refused to go back to the “freedom of choice” plan, and the boycott continued through the fall. As winter arrived, blacks in Hyde County upheld the boycott with more conviction than ever, and more protesters were arrested. Hyde County became a powder keg of racial tension, ready to blow at any moment.114

The spark occurred in July 1969 when a sniper fired on a car carrying four young black passengers as they drove by a Klan meeting at the Middletown crossroads. As word spread, 185 black citizens, many of them armed, confronted the group of 80 Klansmen in a two-hour standoff. As the Klansmen set a cross on fire, shots rang out and a hail of bullets ripped through the air. No one was seriously injured, but a black girl and several police officers suffered minor injuries.115

Desperate to ease tensions, the state superintendent named a new Hyde County superintendent, R.O. Singletary, who had experience in desegregation. A two-man team of state-appointed desegregation experts, Gene Causby and Dudley Flood, arrived in June to begin the work of traveling the county, listening to residents, and learning their history. This team spent months as liaisons between the protesters and the county school board, opening up lines of communication in hopes of reaching an agreement.116 At one meeting with residents, Flood took out a two-toned rubber ball he’d bought at a gas station. The rubber paddle ball was red on one side and green on the other. He presented it to the crowd and asked them what color the ball was. “It’s red,” they replied. Flood continued, “I see a green ball; this ball is green to me.” Flood later said he knew if he could convince the people of Hyde County that both black and white could be greater parts of a whole, then perhaps progress could be made.117

Still unable to produce a plan in the summer of 1969, the school board and boycott leaders agreed to keep segregation intact until they could agree on a desegregation plan for the 1970–71 school year. HEW denied this petition and demanded that Hyde County desegregate immediately. In July, school leaders decided on a new tactic: They would place a desegregation plan up for a bond issue. Busing black students to white schools meant new buildings had to be built to accommodate the influx of students, at a cost of $500,000 plus a debt service of $350,000 over 25 years. If that plan was rejected at the polls, the only solution left was to agree to keep the black schools operating with integrated student bodies. Their petition to halt desegregation denied, Hyde County blacks were at the mercy of the county’s white voters.118

Voters took to the polls on November 5, 1969 and defeated the bond by a four-to-one margin. Both of the county’s historically black schools would be included in the desegregation process; the boycott was successful. For white voters, the tax increase needed to pay for the bond had proven too much to stomach. But local whites also liked the idea of a more community-based school district and lamented the fact that a handful of powerful white men had been making decisions for the whole county populace.119 Others were simply moved by the conviction of their black neighbors — perhaps Dudley Flood’s paddle ball prompted their change of heart.

The Swann Decision and Desegregation

In 1971, the Supreme Court found in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools that school districts could use busing to implement desegregation in public schools.120 The Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system quickly became a desegregation model for districts around the country. It seemed the promise of Brown might finally be realized in Mecklenburg County — but even as Charlotte schools gained racial balance, black students were bused more often and for longer distances than white students.121

Conditions for education continued to improve under the Holshouser administration. Upon taking office in 1972, Governor Holshouser proposed plans to expand kindergarten, reduce class size, and renovate school buildings. The state allocated $300 million for new school construction and provided more benefits for educators and administrators. The Primary Reading Program, founded in 1975, provided assistants in each classroom in third grade and below and professional development for educators.122

In response to increasing desegregation, white families began moving to suburban school districts or enrolling their children in private schools — a continuation of the white flight phenomenon that had begun in the 1960s. According to Batchelor, “By 1970, more than 230 new private academies, most enrolling only white students, had opened in North Carolina. More than 35,000 white students had enrolled in private, all-white schools by 1971.”123 These schools did not hide their intentions in efforts to recruit white students — one promotional brochure from Halifax County read,

“It is the earnest conviction of the trustees of Enfield Academy, Inc. that the integrity and improvement of the different races can best be accomplished by maintaining a segregated school.”124

These “white academies” popped up all over the state.

Most whites, though, stayed in the public school system and sent their children to desegregated schools. Through busing, 99.5% of the state’s black students attended desegregated schools during the 1972–73 school year. Furthermore, “over 90 percent of the state’s school systems had been formally declared unitary […and] North Carolina was operating the most thoroughly desegregated school system in the South.”125 But just a few years later, the forces of resegregation began to lay their foundations.

Desegregation began to slow by the late 1970s in many parts of the state as white flight shifted racial demographics between city and county school districts. In 1975, for example, the student body in Franklin County schools was 54.6% black and 45.3% white. By 1985, the black percentage dropped to 48.1%, while the white percentage rose to 51.7%. The opposite trend occurred in the City of Franklinton: In 1975, the student body in Franklinton was 61.9% black and 38% white. By 1985, the black population rose to 63.2%, while the white percentage dropped to 36.7. This trend was not isolated to Franklin County — it occurred across the state.126 The Milliken v. Bradley decision in 1974 forbade desegregation orders from crossing district lines, ensuring de facto segregation, especially in urban centers.127 The trend of court decisions allowing resegregation to gain momentum would strengthen in the coming decades.128

Resegregation and the Case of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools

A 1997 ruling appeared to take a step towards racial and economic equity: In the Hoke County Board of Education v. State, or Leandro v. State, the court found the state constitution did not require all school districts to receive equal funding, but that every student had the right to a “sound basic education” and schools in economically poor areas must receive additional funding. Thanks to the intersection of race and poverty in North Carolina, many underfunded districts had high African American enrollment.129 Despite this ruling, the funding disparities that characterized public education in North Carolina remain today despite the fact that Leandro is ongoing.

On the 20th anniversary of the Leandro lawsuit in July 2017, both sides in the Leandro case filed a joint motion requesting an independent consultant to make recommendations on how to meet North Carolina’s obligation set out in the Leandro decision.130 West Ed, the independent consultant selected by the parties, sent its report to the judge overseeing the case on Jun 17, 2019, but the report has not been released to the public as of this writing.131 Concurrently, Gov. Roy Cooper created the Governor’s Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education in 2017 to make recommendations to the state on how to meet its obligations under the Leandro decision.132

Resegregation gained steam after the Capacchione v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools case virtually overturned the Swann decision of 1971.133 School districts were no longer required to use busing as a tool to desegregate schools.134 The era of court-mandated integration efforts in North Carolina was effectively ended at the hands of Judge Robert Potter, who had disagreed with the busing plans of the early 1970s.135 Judge Potter’s decision impacted resegregation throughout the state. In Charlotte, for example, during the 2002–2003 school year, 48% of blacks were attending “black schools,” while in 1999–2000, nearly 30% of white students were attending “white schools.”136 In another example, Forsyth County implemented a school choice policy, abandoning more than two decades of plans promoting racial balance and resulting in the rapid resegregation of Forsyth County Schools.137Statewide, the number of highly segregated schools, where minority students make up at least 90% of the student body, increased from 3.2 % in 1989 to 10.2% in 2010.138

Furthermore, in 2011 North Carolina lifted the cap of 100 charter schools permitted to operate in the state. Absent civil rights standards, charter schools can exacerbate segregation, experts say, and are likely to be more segregated than the traditional public schools in the surrounding area.139 Segregated housing patterns that intersect with socioeconomic status also perpetuate segregation in North Carolina’s public schools — and schools closer to racially segregated neighborhoods have higher percentages of failure rates and poverty.140

Recent developments in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg area make for an illustrative case study. A March 2018 Newsweek article claims, “[In] Charlotte, in 2018, like most other American cities… schools are nearly as segregated as they were before the 1954 Supreme Court decision of Brown,” and quotes area civil rights attorney James Ferguson:

“There is no core of people who are actively pushing for school desegregation … We’re almost back to where we started from.”141

In fact, at the current pace, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools will be “back to where we started from” or worse.

In June 2018, the state legislature passed House Bill 514, allowing the majority-white Charlotte suburbs of Cornelius (85% white), Huntersville (77% white), Matthews (78% white), and Mint Hill (73% white) to create their own charter schools. While some magnet schools in the state have created well-funded integrated facilities and student bodies, since the removal of the artificial cap of 100 charters in 2011, the surge in charter schools has bolstered resegregation. Recent research found that, by 2014, more than a fifth of North Carolina’s charter schools were more than 90% white, compared to a tenth in 1998.142 And while the overall population of North Carolina public schools has become less white, the charter school population has become increasingly white.143 The complexity of this issue should be noted, as charters in the state are very popular in communities of color. Many charter schools are actually majority black and brown, but the degree to which they exacerbate segregation is contested.

While Republican lawmakers claim House Bill 514 has nothing to do with race, critics cite race as the primary motivator. In June 2018, North Carolina NAACP President T. Anthony Spearman said the bill attempted to create “Jim Crow independent schools.”144 Others have said the bill attempts to build a “white fence” around the Charlotte area, or, as Matthews Mayor Pro Tem John Higdon says, the bill is about “kids going to schools near their homes and not being under the constant threat of reassignment.”145

Today: The Promise of Freedom Hill

People often say history takes a linear path towards progress — that current and future generations will inevitably fare better than those who came before them. But the harsh lens of today’s Princeville shows otherwise. The town, and its education facilities, have been battered by floods caused by recent hurricanes.

Princeville now is part of the Edgecombe County School System, where data on race and gender continue to show racial disparities within the public schools. According to the Youth Justice Project, Edgecombe County Schools had 5,999 students during the 2016–17 school year, 56.9% black and 30.1% white. Yet, black female students faced 415 short-term suspensions, compared to only 97 for white females. Black male short-term suspensions numbered 1,321, while their white male counterparts had 250 suspensions. Thus, black male students in Edgecombe County were over five times more likely to be suspended than white male students. In total, black students in Edgecombe County comprised 77.9% of all suspensions, despite being only 56.9% of the total student population.146

Sixty-three students dropped out of high school in Edgecombe County during the 2016–17 school year; 36 were black while 20 were white, a 55% difference. Black students also performed lower than whites and Hispanics on high school end-of-course exams. For the 2016–17 school year, the overall percentage of Edgecombe County high school students considered “college and career ready” was 26.3%. White students fared best at 42.8%, followed by Hispanics at 31.9%, while only 15.6% of black students were considered “college and career ready.”

These racial disparities appeared well before the students got to high school. During the 2016–17 school year, white students in third through eighth grades in Edgecombe County were 2.3 times more likely to score “college and career ready” on end-of-grade exams than black students in the same grades.”147 These data track with statewide trends.148 CREED’s forthcoming report, E(race)ing Inequities, takes a comprehensive look at racial disparities across key academic indicators in North Carolina.

Given the historical tendency for African Americans to associate education with freedom, one must ask:

How “free” are the citizens of Freedom Hill?

Is Freedom Hill a metaphor for the current state of racial equity in North Carolina public schools? Such racial inequality — a product of the deep-rooted history of slavery, Jim Crow, and racism — denies black students not only their state constitutional right to a sound basic education, but also their Fourteenth Amendment right to equality under the law. We are not here by chance or coincidence; the problem of race-based disparities in education has been constructed and preserved for centuries by federal, state, and local governments.

Even now, the task of creating an equitable education system remains an elusive goal. The roots run deep. Perhaps by explaining our state’s history of race and education, we can acknowledge our intentions and strengthen our resolve. The burden falls not only on all citizens of North Carolina, but also on the governance and institutions that have brought us to this point. The march toward Freedom Hill continues.