“The people have a right to the privilege of education and it is the duty of the State to guard and maintain that right.”

These powerful words in our state constitution’s Declaration of Rights led the North Carolina Supreme Court to find a fundamental right to a sound basic education. These words now take center stage in the challenge to be heard next Tuesday in our Supreme Court on opportunity scholarships1, otherwise known as publicly funded vouchers for private schools. Where did these words come from? They were first spoken almost exactly 147 years ago by Samuel Stanford Ashley, a carpetbagger.

North Carolina became the first and only state to have education as a right protected in its declaration of rights.

Reverend Ashley spoke these words on the floor of the 1868 Constitutional Convention on February 15 (see EdNC’s coverage of the convention). He made an amendment to propose this new section when the Declaration of Rights was being debated by the full convention. Ashley’s proposed amendment was adopted. North Carolina became the first and only state to have education as a right protected in its declaration of rights.

So how did this carpetbagger come to propose this amendment in North Carolina? It is as if Ashley’s life was pointing him towards this moment all along.

Ashley’s path to North Carolina began when George Whipple, mathematics professor at Oberlin College, took a “homesick lad” under his care. In this Jacksonian era, the college was known not only for its academics, but also as a driving force in the anti-slavery movement. Whipple was in the thick of it. Ashley graduated in 1840 and returned in 1846 to begin his theological studies. The same year, the American Missionary Association was formed with Whipple’s help. The AMA was a Christian organization dedicated to abolishing slavery and promoting the rights of blacks.

Once the war began, Ashley promptly offered his services to the AMA to go to the South as a missionary. But they do not call upon him – not yet.

Ashley taught and served as principal of a Meeting Street School. He then served for fifteen years as a Congregational minister. The AMA’s beliefs were consistent with those of Congregationalists. In 1860, Ashley collected and sent $6.00 to the AMA to help in releasing Reverend Daniel Worth from prison in North Carolina for circulating antislavery materials. Once the war began, Ashley promptly offered his services to the AMA to go to the South as a missionary. But they do not call upon him – not yet.

It was not until March of 1865 that the AMA summoned him.

A serious problem had arisen in North Carolina. Captain Horace James was a mutual friend of Whipple’s and Ashley’s. A Congregational minister, James was serving as a chaplain in New Bern when the military gave him broad supervisory authority over services for freedmen across the state. Early in 1865, James gave his approval for the AMA to send Brother J.G. Longely to Wilmington to coordinate the efforts to provide schools for freedmen.

It did not go well. Longely quickly accumulated a long list of complaints against him. Teachers wrote in protest, demanding his removal. It was a crisis requiring immediate action. James and Whipple both believed Ashley was the right person. With great haste, Ashley was brought by steamer to Wilmington in April of 1865. About a week later, James wrote to Whipple of the transition, praising Ashley: “he is calm and judicious and has already won the confidence of teachers and freedmen.”

By May, Ashley established eight schools, including the Williston School – which would become a source of pride and community for African Americans for years to come.

By May, Ashley established eight schools, including the Williston School – which would become a source of pride and community for African Americans for years to come. Given his successes, other communities solicited his help in building schools so it is not long before he was traveling to Fayetteville, Lumberton, Goldsboro, Smithfield, Bladenboro, and Rockingham.

This led him to want to be a part of the 1868 constitutional convention where he could make sure this progress was not lost and, in fact, expanded. He was elected as a delegate from New Hanover County. Given all of his experience, he was made chair of the education committee of the convention. His fingerprints are all over the education provisions. Once the convention approved the newly-created constitution, it was submitted to the people. At the same time that the people voted to adopt this constitution, they also voted to elect Ashley as the first state superintendent of public instruction under this constitution. He was eager to continue his work.

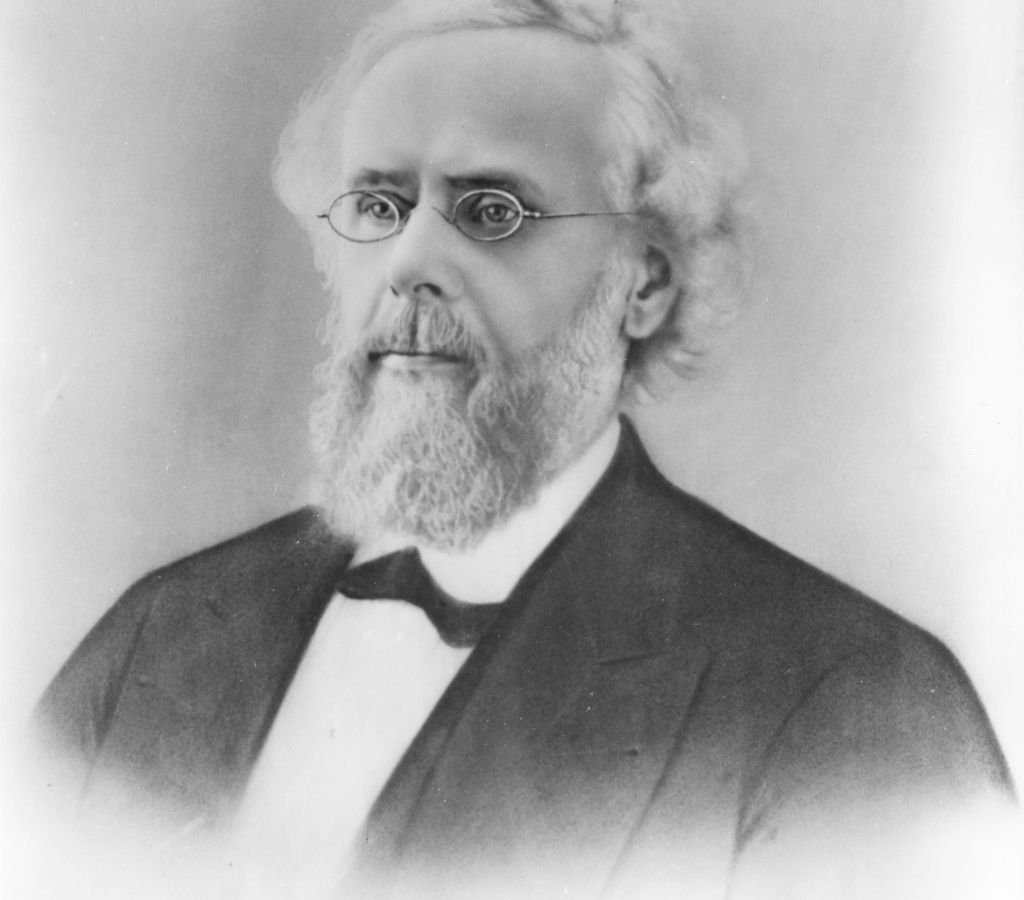

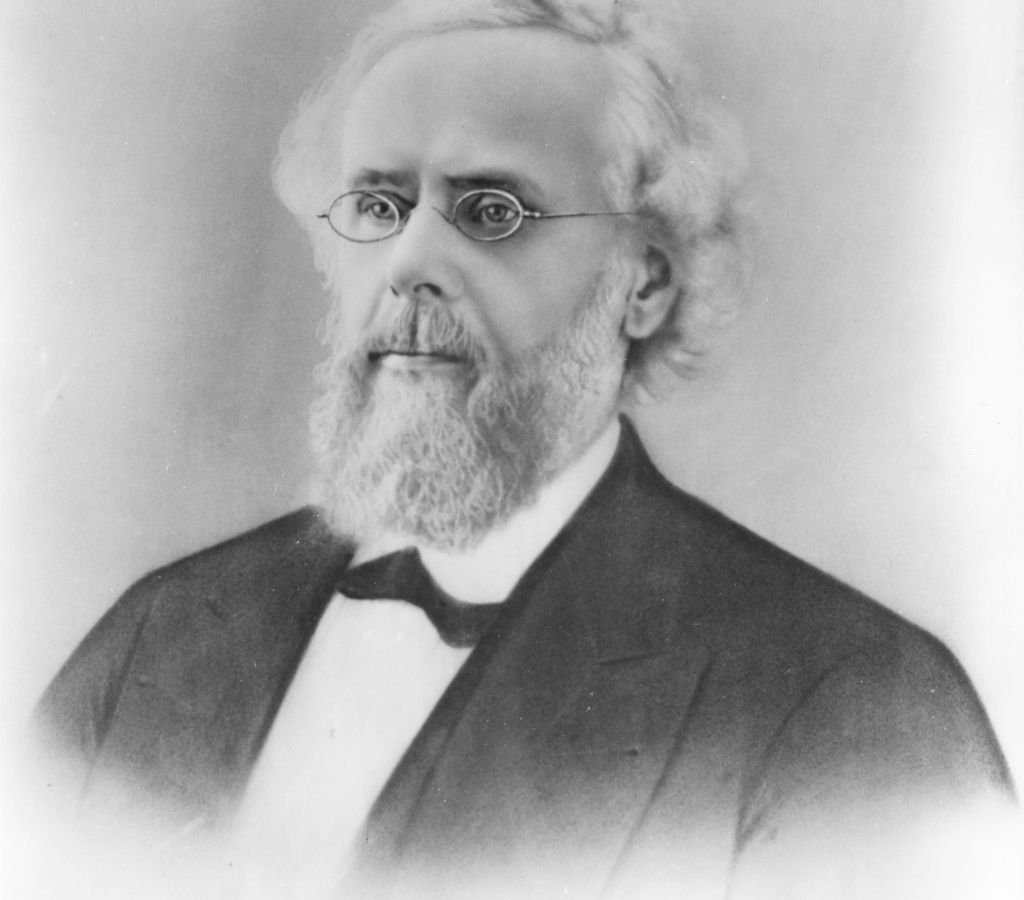

I often speak of Ashley when I give presentations on the state constitution. If I ask participants to raise their hands if they know of Ashley no one does – unless they’ve heard me before. And indeed, at the Department of Public Instruction, there are photos outside of the state superintendent’s office for all elected state superintendents – except Ashley. Instead there is a name plate without a photo. Why? It would seem to be because he is a carpetbagger.

The reasons for a forgotten history is a bigger subject. The EdNC coverage of the 1868 Constitution Convention is one way that we can learn of it. For today, just after the anniversary of the proposal, it is enough to pause and reflect and be grateful for Samuel Stanford Ashley’s continuing impact on North Carolina through this provision that requires the State to guard and maintain the right to education.

Primary sources:

- N.C. Constitution, Art. I, Sec. 15 (1971).

- N.C. Constitution, Art. I, Sec. 27 (1868).

- Samuel S Ashley to ____, Northboro [now Northborough], Mass., August 29, 1860, No. 54775, American Missionary Association, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University.

- S.S. Ashley to George Whipple, Northboro, Mass., December 15, 1862, American Missionary Association, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University.

- William L. Coan to A.M.A., Wilmington, N.C., April 5, 1865, American Missionary Association, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University.

- Captain Horace James to George Whipple, April 10, 1865, No. 99993, American Missionary Association, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University.

Secondary sources:

- Bell, John L., Samuel Stanford Ashley, Carpetbagger and Educator, 72 N.C. Hist. Rev. 456-483 (1995).

The following sources provide additional information:

- Anderson, James D., The Education of Blacks in the South, 1869-1935 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press 1988)

- O’Quinn, Marion Nolan, Carpetbagger Samuel S. Ashley and his role in North Carolina education 1865-1871 (Unpublished Thesis, available at Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina State University 1975).

- Williams, Heather Andrea, Self-taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press 2005).

Editor’s Note: A photo of Stephen D. Poole, superintendent from 1875-76, also is missing from the wall. If you know of high-quality photos of either of the missing superintendents, please let EdNC know.